This week we’re celebrating our annual Women in Games event that spotlights women who have shaped the video game industry, and so it seems fitting to post a blog honoring Margot Comstock, a publishing visionary who helped people become familiar and fall in love with computers and computer games. Sadly, Margot passed away on October 22, 2022.

When Margot Comstock began her work in the 1970s, personal computing was just taking root. Computers, as they first developed after World War II, had been the province of large corporations, governments, and universities, the institutions that could afford these hulking machines. Known as mainframes, their name bespoke their size, massive devices churning out data for the defense industry or international conglomerates. They were operated by conservatively clad men in suits and ties and smartly dressed women in dresses and heels. They were definitely for work, not for play, even if mischievous programmers sometimes sneaked in some lighter fare, like the first baseball simulator.

As technology advanced in the 1960s, the minicomputer, from DEC and other firms, began to build the market. These devices were smaller than the old mainframes (they could fill a large closet, just not a room), but they still ran multiple terminals and were owned by institutions, whether they were private or public. Individuals didn’t own mainframes or minicomputers, though they continued to find ways of creating games like Colossal Cave Adventure or Oregon Trail. Still, only a tiny percentage of the population had access to mainframes or minicomputers, and it was not until the 1970s that a new device, the personal microcomputer, came on the market.

The first microcomputers were devices like the Altair 8800 that took some skill to assemble and get running, so it wasn’t until the debut of devices that were almost completely plug-and-play that the machines found a large audience. Among the manufacturers of these new consumer products, perhaps no maker was more important than Apple. Apple certainly wasn’t the only computer on the market, but with the Apple II the company had a consumer hit that propelled the firm’s success. Here was a (somewhat) reasonably priced device that seemed to promise computing for the masses (or at least the upper-middle-class masses), but left unanswered were the questions: why should you buy one and what could you do with it? That’s where journalists in general entered the picture and, more particularly, Margot Comstock, for she started Softalk, the first general interest magazine pitched directly to Apple II users.

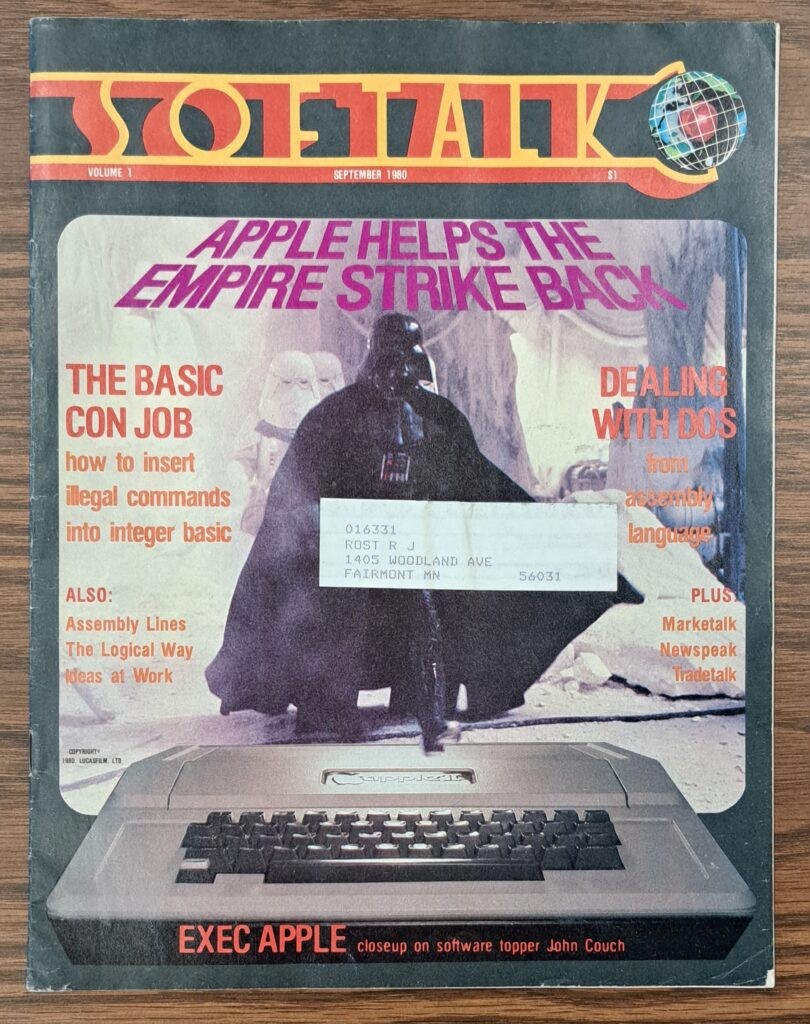

Comstock launched Softalk after earning the startup money for the magazine in a most unusual way—on a television game show. In 1979, she went on Password Plus!, a popular daytime game show. You can watch a clip here. With the money (about $15,000) she won, Comstock planned to buy a home computer. She had experience as an editor already and so had the skills to launch a magazine for Apple users, even if such magazines were still relatively rare. She founded the magazine with her husband Al Tommervik (and often used her married name Margot Comstock Tommervik in the publication), and the magazine debuted with the September 1980 issue.

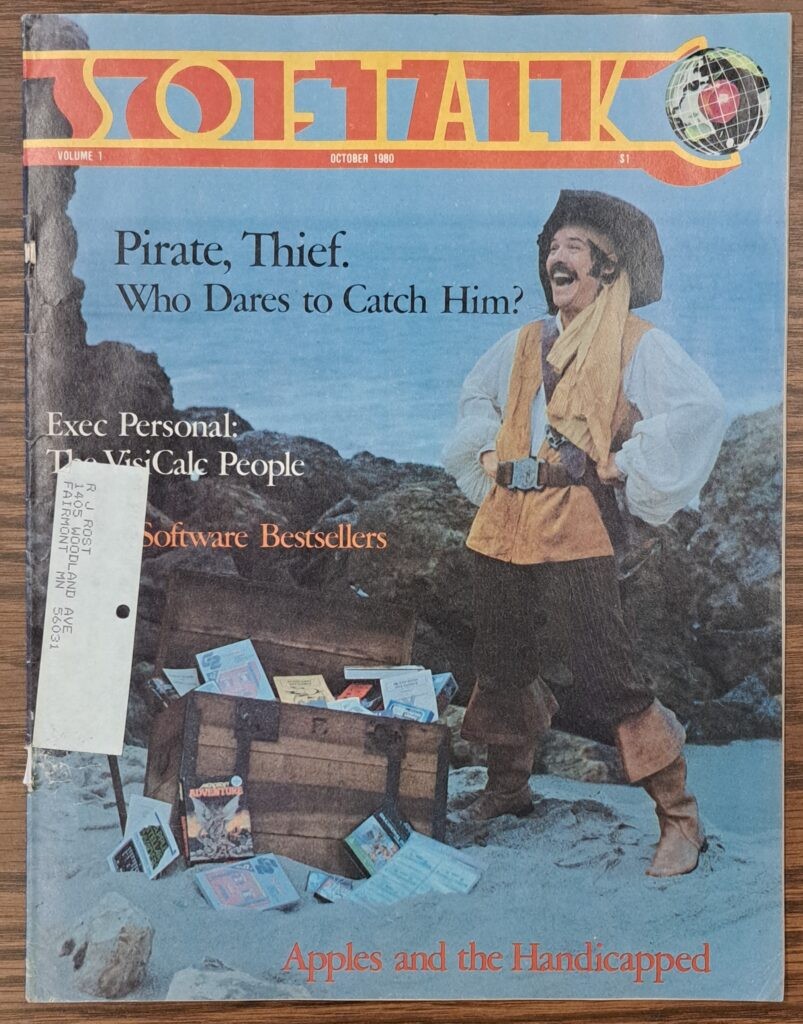

In her opening editorial, Comstock positioned the publication squarely for the general user, describing it as “a feature magazine, intended to pique the curiosity and intrigue the intellect of everyone who owns an Apple.” It combined news of the Apple community, profiles of key leaders (and users), and lots of information about products and programs. While it did feature some programs to type in, it never strove to be strictly a programmer’s magazine. And yet it also was never as purely consumer focused as David Ahl’s Creative Computing, a computer magazine founded in the 1970s. Softalk had lots of information on key business, programmers, and executives in the industry, making it appealing to insiders in the industry who valued the magazine and placed advertising there. A cover article on software piracy—the industry’s biggest headache—gave readers the perspective of software executives who warned that the loss of revenue from copying software hurt innovation (as well as profits, of course).

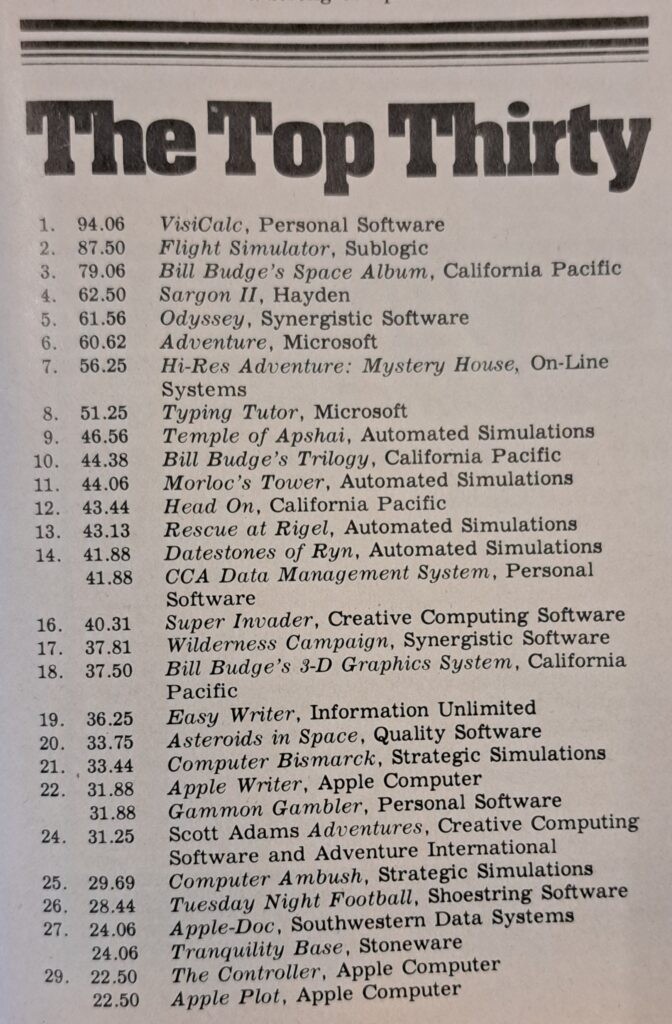

Perhaps the magazine’s most important feature was its list of best-selling games. At a time when information about retail sales was relatively limited, Softalk presented crucial information about what was popular. Granted, its methodologies were somewhat limited—a poll of users. But it still presented valuable data that was hard to find elsewhere. The first poll, in October 1980, showed that while VisiCalc was the most popular piece of software, games dominated the rest of the list. Bill Budge, whose papers are at The Strong, was a leader with three titles, including his Bill Budge’s Space Album which came in at number three. Scott Adams, whose papers are also at The Strong, also appears on that list.

Over the years the magazine evolved and changed. It certainly grew in size! From a thin 28 pages for the inaugural issue in September of 1981 it exploded to a beefy 208 pages a little over a year later in the December 1981 issue. The magazine got slicker too, with a sturdier cover and glossier advertisements. It was a success.

The magazine paid special attention to profiles of key people in the industry. The Feb. 1981 issue, for example, featured profiles of Roberta and Ken Williams (founders of Sierra On-Line Systems) and Bill Budge, while the next month’s issue had an article on “The Women of Apple.” Softalk often took a light, playful tone, joking with its readers and even holding special events like a limerick contest in the March 1981 issue. This one about Sierra Online System’s game The Wizard and the Princess expressed a problem common to players of adventure games:

There once was a wizard, a rake,

Who hunted a Princess to take.

The story’s on line.

The game is just fine.

But how do I get past the snake?!

Anyone who has been stumped by a particularly knotty problem in a game can sympathize!

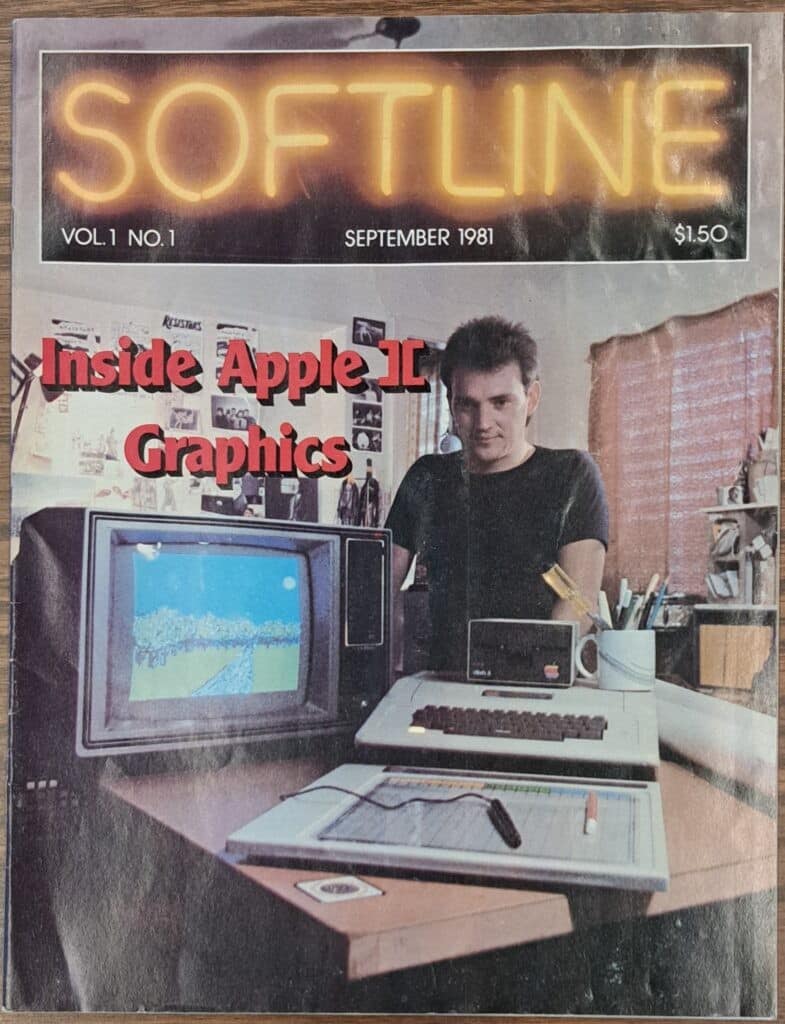

In 1982, as the American economy emerged out of recession and advertisers sought to market their products for microcomputers, Softalk expanded further into a glossy, stiff-covered, and weighty magazine that was the go-to source for information about the Apple and the people who created products for it. Softalk remained a general-interest magazine, while spinning off Softline, a games-focused publication.

In 1984 a slump in the computer industry caused a precipitous drop in advertising, and the August issue of that year proved the last. And yet the magazine’s legacy lived on, not only in the fact that it remains a crucial repository for information about the early history of computer gaming, but also in the personal lives of many people in the gaming industry. Margot Comstock and her husband Al Tommervik, in creating Softalk, helped build a community of people—through the stories they made, the dinners they hosted, and the friendships they fostered—and that is why when you talk to people from that era, they remember Softalk and Margot and Al so fondly. Sometimes the measure of a magazine is not the record it leaves in print but the way it has touched the lives of the people it reaches.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.