Many baby boomers and their children (and maybe their grandchildren too) admire the toy trains of the Lionel Corporation in The Strong’s collections. The toy company, founded in the early 1900s by Joshua Lionel Cowen, reigned as the premier maker of electric train sets for much of the 20th century. In the early 1950s, Lionel outsold its competitors two to one, even though its train sets and accessories were more expensive than the competition. The company aggressively marketed its trains for use by boys and their fathers. The ads promised that the trains would make men of boys and boys of men.

While Lionel clearly directed its advertising to males, it did not ignore women and girls completely. The “fairer” sex, often appeared in Lionel’s ads and catalogues, but their purpose was limited. The advertising positioned the ladies and girls to admire the trains operated by boys and their dads. The males were clearly in charge, and the ladies, usually watching from afar, beamed with appreciation.

It’s not that Lionel never tried to woo the ladies to its products. The company planned on at least two rather conspicuous occasions to manufacture toys specifically for girls. It’s just that Lionel’s toys for girls failed—and spectacularly so.

In 1930 Lionel offered a realistic stove for girls. Standing about 34 inches tall, the stove featured a working oven with built-in thermometer, two functioning electric burners, and a clean porcelain finish. Lionel’s oven bore an amazing likeness to a real kitchen stove, constructed, Lionel advertised, “as substantially as the one Mother uses.” Such a well-made toy, however, came at a cost. And therein lies the stove’s demise: Lionel introduced its authentic-in-every-detail stove in the year after the U.S. economy tanked, signaling the start of the Great Depression. According to Ron Hollander’s All Aboard! The Story of Joshua Lionel Cowen and His Lionel Train Company (2000), the toy stove, at $29.50, cost as much as Mom’s gas stove. Purchasing the toy stove commanded more than a public school teacher made in a week in the 1930s. At a time when Americans faced 25 percent unemployment, few could afford such a toy. (Flop number one)

In 1930 Lionel offered a realistic stove for girls. Standing about 34 inches tall, the stove featured a working oven with built-in thermometer, two functioning electric burners, and a clean porcelain finish. Lionel’s oven bore an amazing likeness to a real kitchen stove, constructed, Lionel advertised, “as substantially as the one Mother uses.” Such a well-made toy, however, came at a cost. And therein lies the stove’s demise: Lionel introduced its authentic-in-every-detail stove in the year after the U.S. economy tanked, signaling the start of the Great Depression. According to Ron Hollander’s All Aboard! The Story of Joshua Lionel Cowen and His Lionel Train Company (2000), the toy stove, at $29.50, cost as much as Mom’s gas stove. Purchasing the toy stove commanded more than a public school teacher made in a week in the 1930s. At a time when Americans faced 25 percent unemployment, few could afford such a toy. (Flop number one)

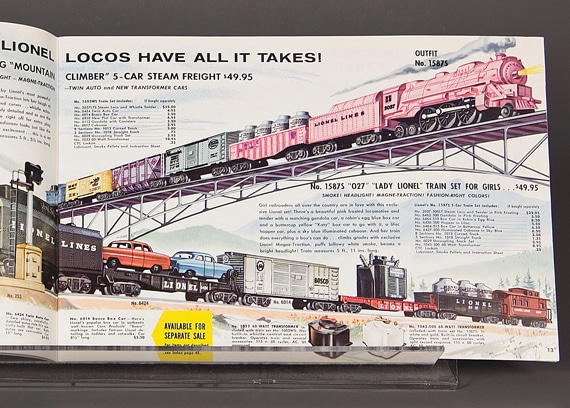

Lionel tried for toys aimed at girls again in the late 1950s. The sales of the company’s toy train sets had leveled off, and executives introduced a number of new products and variations on old products to raise sales. But where in the 1930s it tried authenticity to sell toy stoves for girls, in the 1950s, Lionel produced a “Lady Lionel” train set based on pure fantasy. With perhaps more optimism than sense, Lionel’s catalogue cried: “Girls, you wanted it! Here it is . . . a real Lionel train set in soft, pastel shades!” The girl’s train sported a “beautiful, pink-frosted steam locomotive,” boxcars in “robin’s egg blue” and “buttercup yellow,” a lilac-colored hopper, and a sky blue caboose. Lionel, you might say, missed their new market by a railroad mile. Girls that wanted their own train sets wanted ones just like their brothers’ because, Hollander points out, these sets, in their realism and detailing looked so much like the real thing. Young operators could pretend they were real train engineers. Pink locomotives rather detracted from the make-believe. Lionel released the pastel sets in 1957 and sold very few. Most retailers tried to return the trains to Lionel or sheepishly took them home to their own daughters. (Flop number two)

So, did Lionel learn its lesson? It probably did learn to stick to what it did best, but the wisdom hardly helped. By the end of the 1950s, the era of electric toy trains was fading, and by 1967 Joshua Lionel Cowen’s company filed for bankruptcy. General Mills (maker of Cheerios) devoured it in 1969.