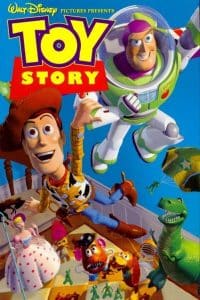

The introduction of Computer-Generated Imagery (CGI)—the application of computer graphics to create images in media—in the 1990s moved many illustrators away from traditional frame-by-frame, two-dimensional animation techniques. John Lasseter demonstrated the possibilities of CGI when he directed Toy Story, the first feature-length computer-animated film, for Pixar in 1995. Shortly after the release of Toy Story, the medium took off. CGI proved more efficient and created a new aesthetic. In the past few years, however, cel animation or hand-drawn animation techniques have regained popularity.

The introduction of Computer-Generated Imagery (CGI)—the application of computer graphics to create images in media—in the 1990s moved many illustrators away from traditional frame-by-frame, two-dimensional animation techniques. John Lasseter demonstrated the possibilities of CGI when he directed Toy Story, the first feature-length computer-animated film, for Pixar in 1995. Shortly after the release of Toy Story, the medium took off. CGI proved more efficient and created a new aesthetic. In the past few years, however, cel animation or hand-drawn animation techniques have regained popularity.

Some commentators argue that CGI has highlighted a paradox of animation, the uncanny valley. Researchers and many pop culture critics use the uncanny valley to describe the “odd sense that arises from an encounter with an object that looks real enough to be real, but is nevertheless not real or that seems not quite real.” The human brain no longer processes the visuals as good animation, but instead detects the imperfections of technology. Other critics, like Armond White, editor and chief film critic for CityArts, suggest that “technological excess has overwhelmed narrative meaning” and often “substitutes potentially wondrous details with a certain overripeness of imagery.” In 2013, a group of filmmakers from Pixar Animation Studios, University of Toronto, University of Washington, and Stanford University presented “Stylizing Animation by Example” at the Special Interest Group on Graphics and Interactive Techniques Conference. The group explored how filmmakers might achieve more expressive rendering styles that imitate traditional painting techniques and produce a range of styles that cannot be achieved with 3D computer rendering. Many filmmakers and video game creators continue to grapple with CGI tools, which, despite criticism, provide for new visual possibilities and interactive experiences.

As a fan of works produced in the golden era of American animation (1928-1960s), I gravitate toward other media that presents the aesthetics of cel animation or hand-drawn animation. Video games such as Child of Light, Insanely Twisted Shadow Planet, and Super Mario World 2: Yoshi’s Island share the qualities often associated with traditional animation such as the saturated levels of color, controlled color palette, and creative use of objects to synchronize sound with visuals. Recently, at E3 2015, Studio MDHR presented their forthcoming video game Cuphead, which looks and sounds like a 1930s animated film.

As a fan of works produced in the golden era of American animation (1928-1960s), I gravitate toward other media that presents the aesthetics of cel animation or hand-drawn animation. Video games such as Child of Light, Insanely Twisted Shadow Planet, and Super Mario World 2: Yoshi’s Island share the qualities often associated with traditional animation such as the saturated levels of color, controlled color palette, and creative use of objects to synchronize sound with visuals. Recently, at E3 2015, Studio MDHR presented their forthcoming video game Cuphead, which looks and sounds like a 1930s animated film.

Brothers Chad and Jared Moldenhaur from Studio MDHR designed Cuphead. The pair share aesthetic tastes inspired by the 1930s cartoons they watched in their youth, and decided to create a run and gun platform game that resembles the work of some of their favorite animators—Grim Natwirkc, Willard Bowsky, Ub Iwerks, and Max Fleischer, among others.

The game follows Cuphead as he attempts to repay his debts to the devil. Cuphead encounters continuous boss fights and has the ability to earn special skills throughout the game. The visuals in the game preview prove magical. Cuphead employs the “plausible impossible,” a technique that Walt Disney used in cartoons like Thur the Mirror in 1936 and elaborated on in an episode of the Disneyland television program he hosted in the 1950s. The premise of “plausible impossible” is that drawings and animation make things that are impossible seem possible. For example, Cuphead features humanized root vegetables like carrots and potatoes, an agitated steamboat, and an aggressive slot machine. Everything in the world of Cuphead is alive.

The Moldenhaur brothers drew more than 150 different characters before they settled on Cuphead as the protagonist (Mughead is also playable for 2-player games). The brothers found the inspiration for Cuphead from a 1936 Japanese propaganda cartoon in which Japanese forces fend off a corrupt Mickey Mouse. In the cartoon, a man with a teacup for a head morphs into a tank. Cuphead has the body of Mickey Mouse and a tea cup for a head.

Cuphead not only looks like a vintage cartoon, but the brothers used the 1930s tools of the trade to make the game. Chad hand-drew the animation and painted the backgrounds, creating beautiful watercolor scenes. Jared honed his skills in traditional Foley arts to create all of the sounds for the game. Foley means that the sound technician sits in a recording studio and recreates sounds from real world objects such as the swishing of silk, the stamping Oxfords to denote footsteps, or the squeak of a door. The brothers also commissioned jazz musician Kristofer Maddigan to create and record an original score via analogue rather than digital means.

The dialog surrounding the development and forthcoming release of Cuphead evokes the tone and mood of the Golden Age of American animation. While sophisticated technologies like CGI provide innovative ways to develop interactive experiences, I am thrilled to see a game that showcases hand-drawn animation and Foley arts. I often feel connected to media produced by traditional animation techniques, because they reveal the flaws, quirks, and talents that are derived from the human-hand.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.