Fans of The Bachelorette and romance novels might be interested to know that The Coquette and her Suitors recently joined The Strong’s collections. This 1858 game features some of the most detailed design and lithography available at that time and undoubtedly drew its title from one of the most popular novels of that era, first published anonymously in 1797. The Coquette: or, The History of Eliza Wharton was still a best-seller some 50 years later and was not credited to an author until 1856, 16 years after novelist Hannah Webster Foster had died. Two years later, the Boston publisher and bookseller Brown, Taggard & Chase named a board game after the book’s protagonist, whose coquettish behavior led to her early demise. The book tells a sad story of a good girl whose dream of independence was overcome by society’s rules. But the board game paints her quite differently and the publisher probably only chose the game’s title for the mass recognition of the term “coquette.”

Fans of The Bachelorette and romance novels might be interested to know that The Coquette and her Suitors recently joined The Strong’s collections. This 1858 game features some of the most detailed design and lithography available at that time and undoubtedly drew its title from one of the most popular novels of that era, first published anonymously in 1797. The Coquette: or, The History of Eliza Wharton was still a best-seller some 50 years later and was not credited to an author until 1856, 16 years after novelist Hannah Webster Foster had died. Two years later, the Boston publisher and bookseller Brown, Taggard & Chase named a board game after the book’s protagonist, whose coquettish behavior led to her early demise. The book tells a sad story of a good girl whose dream of independence was overcome by society’s rules. But the board game paints her quite differently and the publisher probably only chose the game’s title for the mass recognition of the term “coquette.”

A coquette, according to Merriam-Webster, is a woman who flirts without sincere affection. Half a century after the novel first appeared, the board game labeled its coquette pawn an “heiress,” while the other players’ pawns appeared as men who pursued her. In 19th century terms, all these male pawns, whether artist, farmer, pastor, merchant, or mechanic, represented honorable professions. Each pawn’s pathway on the game board is marked for advances and setbacks. When one reaches “disappointment,” for example, he must go back and start over, while simple “apprehension” or “hope” cause no delay. The game’s coquette simply stands at the center of the board where the first pawn to attain her “approbation” wins the game and, since she’s an heiress, her wealth. It seems silly today.

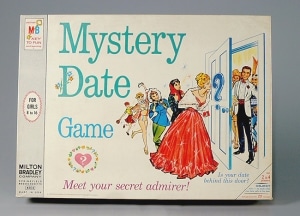

But silliness and romantic games weren’t confined to the 19th century. In the 1960s, just about a century later, Milton Bradley produced a board game for young girls called Mystery Date, in which players traverse a board picking out clothing for an event and open a door on the game board to reveal a dream date “dude” or a slovenly “dud.” If a player’s outfit matches the dude’s event-specific clothing, she wins. It plays like the gender reverse of The Coquette and Her Suitors. Although the New York Times labeled Mystery Date politically incorrect in the 2000s, and it undoubtedly represents some of the worst gender stereotyping of any board game, it has undergone three subsequent revisions and remains available. Meanwhile, the original 1965 version is among the most collectible of mid-20th century mass-produced board games.

In life as in board games, fashions may change but romance persists generation after generation. Looking at The Coquette and Her Suitors side-by-side with Mystery Date reveals the ways that playing at romance continues and makes me wonder what the next hundred years will bring. I hope that my curatorial successor in 2118 will be ready to grab a copy of Mystery Date: The Matrix Edition for the museum’s collection.