Allow me to introduce you to an elite group of which I am not a member: serious gamers. Yes, I’ve been known to play the occasional game of Scrabble, and in my youth I devoted a week one summer to playing Monopoly with a cousin. Add in a few random games of Checkers, Parcheesi, and Go Fish, and that about covers it. So when I say “serious gamer,” I’m referring to someone like the extraordinary Sid Sackson.

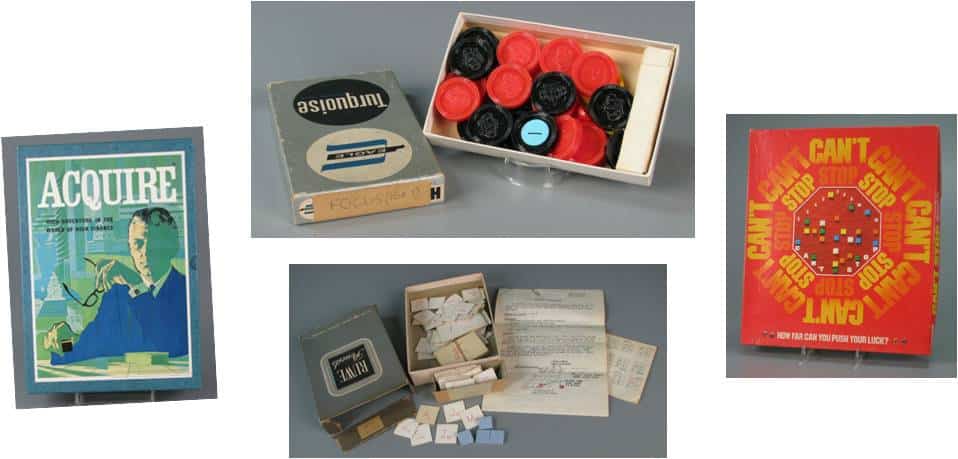

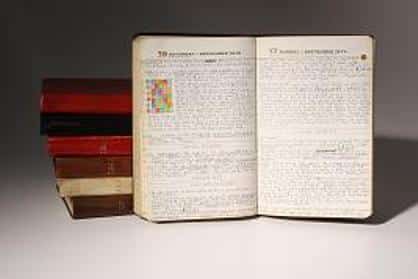

Although he’s not a household name to the general public, Sackson is recognized and beloved both here and abroad for his many contributions to games as a game designer, collector, author, and skilled player. The Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong is the fortunate beneficiary of an exceptional collection of Sackson’s personal game archive. A born game player and an engineer by profession, Sackson left the engineering field behind and surrendered entirely to his love of gaming by 1970. Whether reviewing board games for Strategy & Tactics, developing a new game of his own, suggesting tactics to other game designers, or playing games with his wife and friends, Sackson stayed ever alert to what worked in a game and what didn’t. The game diaries he maintained from 1963 to 1997 make a detailed and fascinating record of the gaming world.

As an outsider to the community of game enthusiasts, I’ve found Sackson’s diaries a revelatory path for exploring the evolution and appeal of games. Not only did Sackson record every gaming book and magazine that he received, every letter he wrote or received, every game he played and with whom, and his thoughts and illustrations of games he was developing, he also provided detailed indexes to all of them! Courtesy of those indexes, I invite you to come with me through this singular gateway that let me into the world of fantasy games. And many of you will not be surprised that the key to unlock the door is the name “Gary Gygax.”

As an outsider to the community of game enthusiasts, I’ve found Sackson’s diaries a revelatory path for exploring the evolution and appeal of games. Not only did Sackson record every gaming book and magazine that he received, every letter he wrote or received, every game he played and with whom, and his thoughts and illustrations of games he was developing, he also provided detailed indexes to all of them! Courtesy of those indexes, I invite you to come with me through this singular gateway that let me into the world of fantasy games. And many of you will not be surprised that the key to unlock the door is the name “Gary Gygax.”

From simple curiosity, I checked the name index to Sackson’s 1975 diary for any reference to Gygax. I found this notation: “1/25/75: Rcd. Europa #4/5 Article on Dungeons & Dragons, with mention of Chainmail (Book & Game).” Then, from his magazine collection, I retrieved the referenced issue of Europa, discovering the notation “Rcd. On 1/25/75 written on its cover—his trails lead both ways. The full title of Gygax’s article is “What Dungeons & Dragons is All About and How to Go About it All, Part I.” Never having played Dungeons & Dragons, but keenly aware of its popularity and impact on gaming, this seemed an auspicious place to begin my personal quest to gain an appreciation of its importance.

From simple curiosity, I checked the name index to Sackson’s 1975 diary for any reference to Gygax. I found this notation: “1/25/75: Rcd. Europa #4/5 Article on Dungeons & Dragons, with mention of Chainmail (Book & Game).” Then, from his magazine collection, I retrieved the referenced issue of Europa, discovering the notation “Rcd. On 1/25/75 written on its cover—his trails lead both ways. The full title of Gygax’s article is “What Dungeons & Dragons is All About and How to Go About it All, Part I.” Never having played Dungeons & Dragons, but keenly aware of its popularity and impact on gaming, this seemed an auspicious place to begin my personal quest to gain an appreciation of its importance.

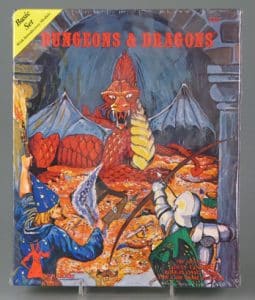

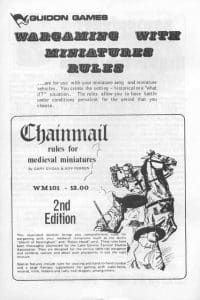

Instantly, I learned that Dungeons & Dragons was not only a new game introduced in 1974, but a new type of game—“fantasy wargaming.” Now I had to learn something about wargaming and miniature wargaming. Gygax refers readers to his medieval miniature wargame Chainmail which he developed with Jeff Perren in 1971. The rules for this game contain a section at the end entitled the “Fantasy Supplement.” Gygax writes that he and his friend Dave Arneson developed the rules for Dungeons & Dragons from this one section.

Instantly, I learned that Dungeons & Dragons was not only a new game introduced in 1974, but a new type of game—“fantasy wargaming.” Now I had to learn something about wargaming and miniature wargaming. Gygax refers readers to his medieval miniature wargame Chainmail which he developed with Jeff Perren in 1971. The rules for this game contain a section at the end entitled the “Fantasy Supplement.” Gygax writes that he and his friend Dave Arneson developed the rules for Dungeons & Dragons from this one section.

Gygax’s insight into what set fantasy wargaming apart from other simulation games interested me most. Before a fantasy wargame can begin, the referee creates a world in which all play will evolve. Unbound by the restraints of the real world, the imagination of each player is likewise unbound. Gygax went on to explain that his inspiration for fantasy play included R. E. Howard, Fritz Leiber, and the legends of King Arthur.

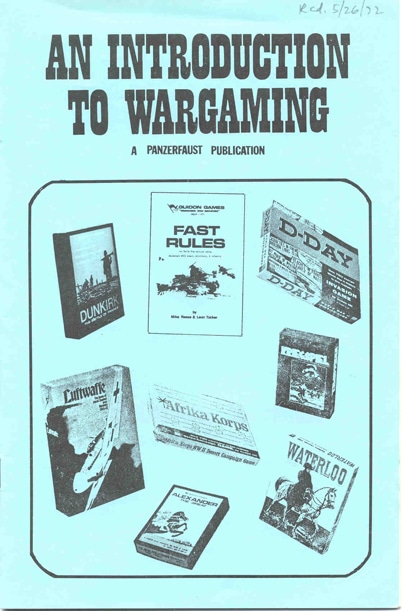

To learn more about wargaming, I looked further back in Sackson’s diaries to 1972 and found a reference to an ad from Panzerfaust, a wargaming magazine, mentioning their booklet “An Introduction to Wargaming.” Of course, Sackson had a copy. In it, the first article I encountered was “How Can War Be a Game?” by Gary Gygax. A legitimate question I thought, to which he gave an interesting answer, quoting from Winston Churchill’s book River War: “We live in a world of ‘ifs.’ ‘What happened’ is singular; ‘what might have happened,’ legion.” Gygax goes on to say that “it is into the realm of ‘ifs’ that the wargamer plunges into, finding in it diversion, challenge, and an outlet for both his creativity and competitive instinct.”

To learn more about wargaming, I looked further back in Sackson’s diaries to 1972 and found a reference to an ad from Panzerfaust, a wargaming magazine, mentioning their booklet “An Introduction to Wargaming.” Of course, Sackson had a copy. In it, the first article I encountered was “How Can War Be a Game?” by Gary Gygax. A legitimate question I thought, to which he gave an interesting answer, quoting from Winston Churchill’s book River War: “We live in a world of ‘ifs.’ ‘What happened’ is singular; ‘what might have happened,’ legion.” Gygax goes on to say that “it is into the realm of ‘ifs’ that the wargamer plunges into, finding in it diversion, challenge, and an outlet for both his creativity and competitive instinct.”

This evaluation of wargaming by Gygax in 1972 relates directly to his embrace of fantasy wargaming in his development of Chainmail in 1971 and his defense of it in his article on Dungeons & Dragons, Part I: “While the military–type simulation has only history to use, the fantasy game has history, legend, fables, folklore, and the works of many imaginative authors to draw upon.” He adds, “Fantasy games allow nearly—perhaps totally—free rein to the minds engaged in their play.”

Will this new-found insight make me a gamer? No, but it does give me what I value most—understanding. Thank you Sid Sackson. It was fun!