For more than a century, the newspaper trade has had to determine creative ways to prevent a decrease in circulation and to find new subscribers. In the late 1800s, the Sunday edition of newspapers began to carry art supplements, which included parlor prints and toys for kids to cut out and assemble. Art supplements proved an innovative way to build an audience—each week parents read about the next must-have paper toys in the following week’s newspaper.

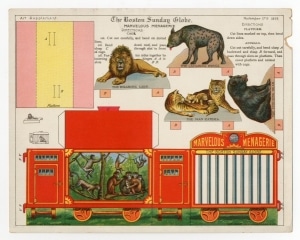

Some companies used the art supplement section to advertise. In 1895, the Boston Globe printed an intricate playset called “The Marvelous Menagerie” as created by Arm Strong & Co. (likely a gun and rifle manufacturing company). The menagerie included a roaring lion, the “man eaters” (tigers), a laughing hyena, and a cuddling bear. When assembled, the cage could hold any of the animals. During the Victorian era, the rising urban middle class had little contact with working or wild animals and people tended to romanticize animals, often delighting in the idea of companion animals. Parents and moralists felt that providing children with pets helped cultivate virtues and counteract boys’ tendencies toward violence. These paper toys also provided a subtle way to remind readers of the value of the newspaper. Not only did readers get the latest news, but they also received a toy to entertain their children.

Some companies used the art supplement section to advertise. In 1895, the Boston Globe printed an intricate playset called “The Marvelous Menagerie” as created by Arm Strong & Co. (likely a gun and rifle manufacturing company). The menagerie included a roaring lion, the “man eaters” (tigers), a laughing hyena, and a cuddling bear. When assembled, the cage could hold any of the animals. During the Victorian era, the rising urban middle class had little contact with working or wild animals and people tended to romanticize animals, often delighting in the idea of companion animals. Parents and moralists felt that providing children with pets helped cultivate virtues and counteract boys’ tendencies toward violence. These paper toys also provided a subtle way to remind readers of the value of the newspaper. Not only did readers get the latest news, but they also received a toy to entertain their children.

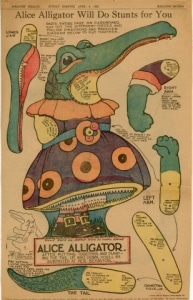

Moving toys or lever and pin paper toys were often featured as art supplements. Artist Dan Rudolph produced dozens of these paper toys in the 1920s. Little seems to be known about Rudolph, but his paper toys printed in the Syracuse Herald were richly colored, intricate pieces. Some of these included Tommy Tiger dressed in blue and red checkered pants with suspenders, The Rooster with brilliant green feathers, Alice Alligator with a snapping lower jaw, Bunny Rabbit with a basket of colorful eggs, and Oscar the Owl sharply clad in a top hat. Readers were instructed to paste the piece onto cardboard, cut out the different pieces, and then to follow the instructions on the back. Moving toys or lever and pin toys were jointed together with either a paper fastener or a string joint. When all the parts were joined, a string was usually tied to specific sections on the back, and the string was then tied to a stick, a pencil, a penny, or other weight. This served as the control. These simple paper toys taught scientific principles of mechanical motion.

Moving toys or lever and pin paper toys were often featured as art supplements. Artist Dan Rudolph produced dozens of these paper toys in the 1920s. Little seems to be known about Rudolph, but his paper toys printed in the Syracuse Herald were richly colored, intricate pieces. Some of these included Tommy Tiger dressed in blue and red checkered pants with suspenders, The Rooster with brilliant green feathers, Alice Alligator with a snapping lower jaw, Bunny Rabbit with a basket of colorful eggs, and Oscar the Owl sharply clad in a top hat. Readers were instructed to paste the piece onto cardboard, cut out the different pieces, and then to follow the instructions on the back. Moving toys or lever and pin toys were jointed together with either a paper fastener or a string joint. When all the parts were joined, a string was usually tied to specific sections on the back, and the string was then tied to a stick, a pencil, a penny, or other weight. This served as the control. These simple paper toys taught scientific principles of mechanical motion.

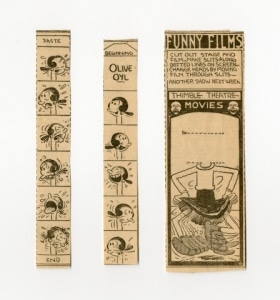

In 1919, E. C. Segar penned Thimble Theatre, a small format comic strip starring Olive Oyl, her brother Castor Oyl, and her boyfriend Harold Ham Gravy. The strip was printed in William Randolph Heart’s New York Journal. Thimble Theatre presented down-to-earth physical comedy and engaging storytelling that many readers gravitated toward. When Popeye the Sailor joined the crew, the school of hard knocks philosophies became more prominent in the comic strip. In the 1930s, Segar created Funny Films Thimble Theatre Movies. These fluff pieces were also printed in the newspaper. Readers were instructed to cut out the stage and the film strip, to make slits along the dotted lines on the screen, and to change the heads by moving the films through the slits. Readers were encouraged to tune back for “another show next week.” Funny Films Thimble Theatre Movies were a simple way to increase the frequency of readers’ contact with the paper.

Paper toys printed in the newspaper proved a clever means to attract subscribers and retain revenue. While parents thought the toys provided their children with a quiet, solitary pastime, assembling these paper toys also encouraged children’s artistic talents, creativity, and interest in the principles of motion. Although many of us rarely see a physical newspaper today, these vintage toys can still serve as entertaining craft projects for kids during these stay-at-home days. Just enlarge the blog illustrations, right click to copy the image, paste it into a blank document, print, and there you go—fun paper crafts a century after they first appeared in print.

Paper toys printed in the newspaper proved a clever means to attract subscribers and retain revenue. While parents thought the toys provided their children with a quiet, solitary pastime, assembling these paper toys also encouraged children’s artistic talents, creativity, and interest in the principles of motion. Although many of us rarely see a physical newspaper today, these vintage toys can still serve as entertaining craft projects for kids during these stay-at-home days. Just enlarge the blog illustrations, right click to copy the image, paste it into a blank document, print, and there you go—fun paper crafts a century after they first appeared in print.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.