By: Eva Maria Rey Pinto, 2025 Valentine-Cosman Research Fellow

Ever wonder how America’s sweetheart snuck into every corner of the Americas? In 1974, Mattel’s founders, Ruth and Elliot Handler, resigned after financial scandals and IRS investigations. This sparked a crisis lasting through the 1980s. New leadership pivoted by licensing Barbie to global toy companies, reducing production costs while maintaining profits through local production and distribution, preserving the brand’s success. Given its geographic proximity, the Latin American market held strategic interest for Mattel. However, during this period, most South American countries had adopted protectionist economic policies aimed at shielding local industries from foreign competition. These measures severely restricted international trade and made it nearly impossible for foreign companies to operate directly within national markets.

Chile, after the 1973 military coup, adopted neoliberal policies crafted by the “Chicago Boys”—a group of Chilean economists trained in the United States. Amid Chile’s fully liberalized economy and Mattel’s pursuit of licensing partners, Roberto Betinyanit, founder and CEO of the Chilean toy company Plásticos Gloria, recognized an opportunity. In 1977, Betinyanit traveled to the International Toy Fair in New York, where he initiated discussions with Mattel about acquiring the doll’s license. His son, Enzo, recalls that within a year, Roberto convinced Mattel that Plásticos Gloria could meet the high-quality standards required by the Barbie brand. As a result, Mattel granted the license, and production and distribution of Barbie began in Chile in 1978. This development paved the way for other toy companies in the region, such as Estrela in Brazil, Rotoplast in Venezuela, Basa in Peru, and finally, Dibon in Colombia. The latter became the last South American company to acquire the Barbie license in 1988.

Digging into Mattel’s past can feel like chasing secrets locked away in an impenetrable vault; corporate archives are simply off-limits. However, with the generous support of The Strong National Museum of Play, I got to open a different kind of treasure chest: the Barbie Fashion Papers, which are held by the museum at its Rochester headquarters. For anyone curious about Barbie or Mattel, these papers are a goldmine. Gathered by the legendary Barbie designer Carol Spencer between 1952 and 2023, the boxes contain Mattel’s behind-the-scenes story, marketing studies, photos, sketches, catalogs, and even sales reports. Out of this archival visit, three discoveries stood out as especially important for my research: (1) Mattel’s marketing gaze on Latin America and Latinx communities in the U.S, (2) Mattel’s anxiety over Barbie knockoffs, and (3) The two faces of Mattel’s licensing strategy.

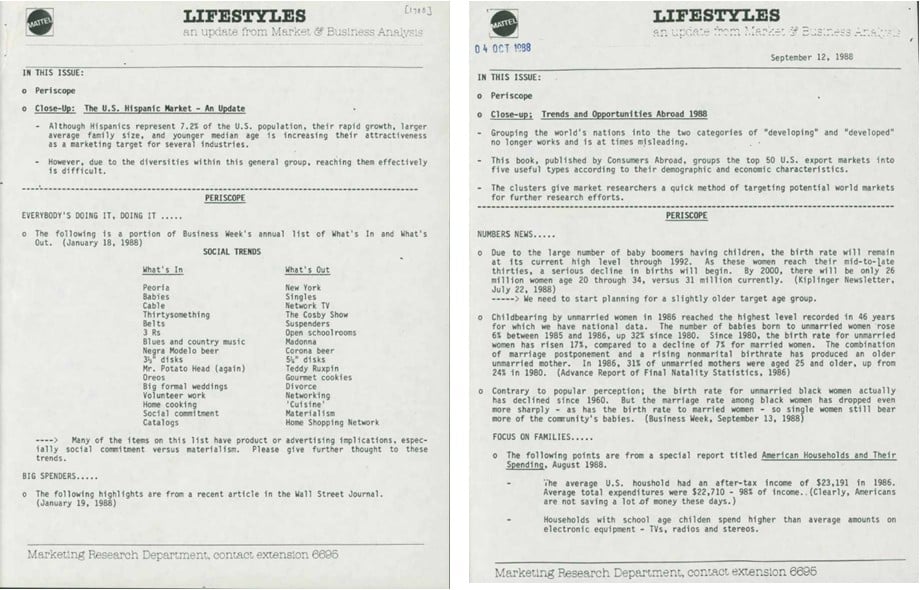

The 1988 Mattel reports titled “Close-Up: The U.S. Hispanic Market—An Update” and “Close-Up: Trends and Opportunities Abroad 1988” reveal both fascination and blind spots. The company’s studies repeatedly treated the region as an “untapped market,” framing Latin American children as future consumers who could be reached with the right combination of aspiration and affordability. Colombia and Chile, in particular, appear as key testing grounds: Chile was noted for its emerging middle class, while Colombia was singled out as a growing but precarious market where piracy and “knock-offs” undercut official Barbie sales.

Chile appears in the reports as a laboratory for Mattel’s middle-class strategy, a country where economic “stability” made Barbie seem within reach of urban families aspiring to cosmopolitan lifestyles. Colombia, meanwhile, was framed through the lens of risk. Mattel fixated on the abundance of “pirate” Barbies (dolls sold in markets and toy stalls at a fraction of the price). The company saw this as a threat to its brand identity, but the popularity of knockoffs also revealed something else: Barbie had already become a household name, reshaped and reimagined by local economies that did not wait for Mattel’s permission.

What stands out most is how Mattel often relied on sweeping cultural stereotypes to imagine these audiences. Reports describe Latin American girls as especially drawn to “fantasy, fashion, and beauty,” as though the entire region shared a single taste palate. At the same time, their U.S. Latinx counterparts were portrayed as a “growing opportunity,” also through sweeping generalizations: family-oriented, traditional, and loyal to recognizable brands. Barbie, researchers suggested, could succeed here by reflecting these values, never mind the diversity and complexity of Latinx experiences. In other words, Mattel was not just selling dolls; it was selling a version of Latinidad that reinforced narrow scripts of femininity.

According to the reports, the anxieties over knockoffs show how Barbie’s global empire was never as stable as her dream house suggested. Mattel devoted significant attention to imitations flooding local markets, from glamorous dolls with suspiciously similar wardrobes to cheaper versions that parents could actually afford. These “pirate Barbies” highlight both the power of local economies to resist corporate control and Mattel’s obsession with brand purity. Latin America emerges as a region of promise and worry, a place where Barbie might thrive but only if she could outshine local competitors and win over families with limited income.

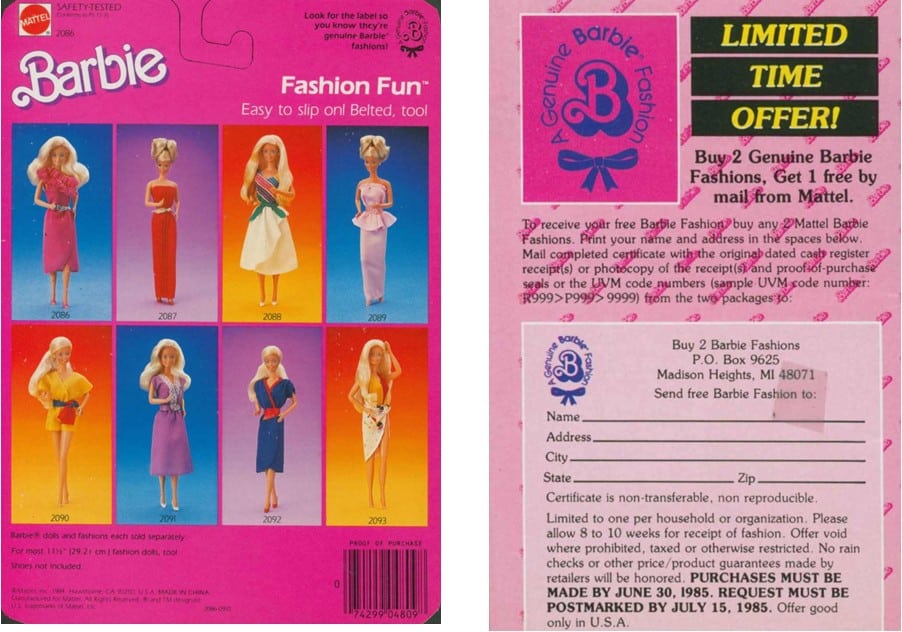

The preoccupation with knockoffs extended from the dolls to the clothes, so in the late 1970s, Mattel introduced a “A Genuine Barbie Fashion” label, which became part of a brand authentication campaign. This aimed to “educate” consumers (parents and kids) to associate the logo with authenticity, making knockoffs look “cheap” or “fake” by comparison. Mattel encouraged children to become little brand guardians who knew what counted as the real Barbie. Additionally, the brand created initiatives as “Buy 2 Genuine Barbie Fashions, Get 1 free by Mail from Mattel.” By actively policing authenticity, the company aimed to create consumer loyalty locally and internationally.

The brand’s growth not only came with the fashion expansion of the doll, but also with all imaginable products. I already knew about licensing Barbie to local toy companies so they could manufacture dolls and accessories within national markets in the 1970s. But the papers at The Strong revealed another layer: how Mattel’s licensing division started. This was an opportunity identified by Carol Spencer when she lived in Japan while working for Mattel’s office there. She noticed that a local store sold different products with Barbie’s face, and it was a success. So, the company decided to capitalize on this opportunity and give the authenticity label to hundreds of other products.

From notebooks and lunchboxes to cosmetics and even food, Barbie’s face became a portable trademark, extending her reach far beyond the toy aisle. This was not simply about play; it was about saturating everyday life with Barbie, turning her into a lifestyle brand. These records make clear that licensing was both a business strategy and a cultural one. By allowing Barbie to appear in stationery, clothing, and household items, Mattel ensured that she was constantly visible to children and their parents, embedding Barbie into the routines of school, home, and leisure.

In marketing reports, this was described as “market penetration,” a term that reveals just how gendered corporate language can be. The phrase casts expansion in masculinized terms, masking how Barbie’s omnipresence worked through the intimate spaces of girlhood.

Taken together, these papers show Barbie’s Latin American story as one of aspiration and anxiety: a blend of business opportunity, cultural stereotyping, and corporate nervousness about losing control. For researchers, they remind us that behind every pink box lies a history of negotiation between global capital and local play.