There’s something liberating about the yo-yo. I keep one on my desk for emergencies—like when a balky sentence has me hanging. You’d be surprised at how a twisted paragraph will straighten out and fly right after a few tosses of a yo-yo. In his superb novel, Stop Time, Frank Conroy wrote, “To yo-yo you have to let go.” And indeed you do; thinking too hard will tangle a yo-yo trick just as it can tie up an idea.

There’s something liberating about the yo-yo. I keep one on my desk for emergencies—like when a balky sentence has me hanging. You’d be surprised at how a twisted paragraph will straighten out and fly right after a few tosses of a yo-yo. In his superb novel, Stop Time, Frank Conroy wrote, “To yo-yo you have to let go.” And indeed you do; thinking too hard will tangle a yo-yo trick just as it can tie up an idea.

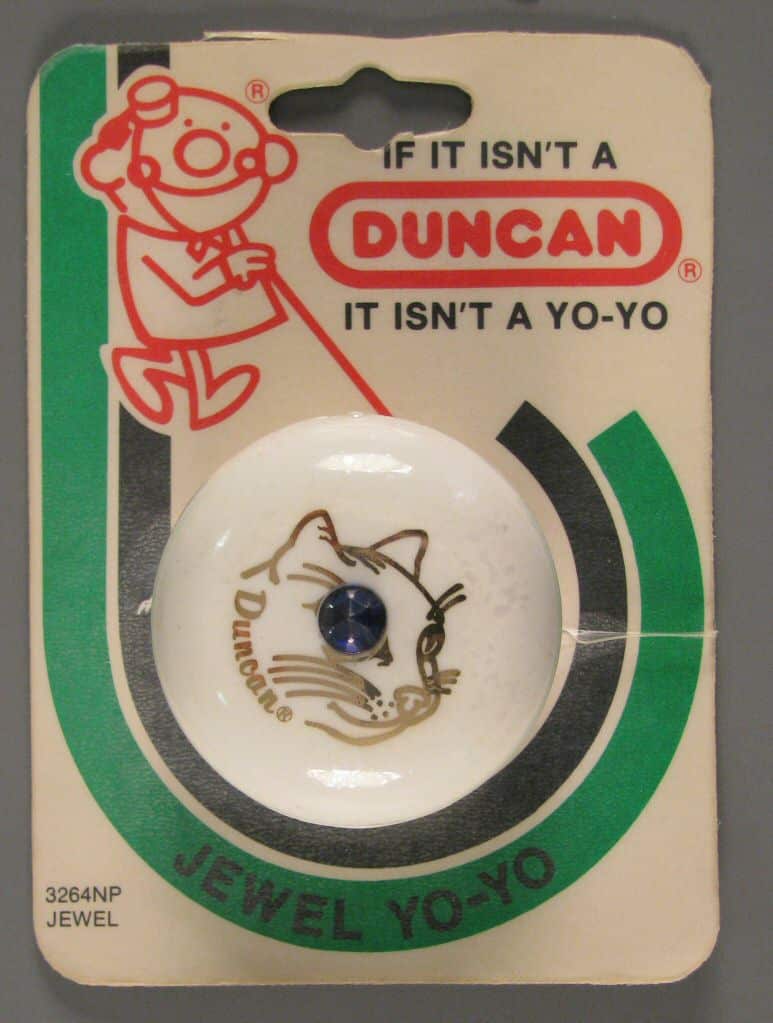

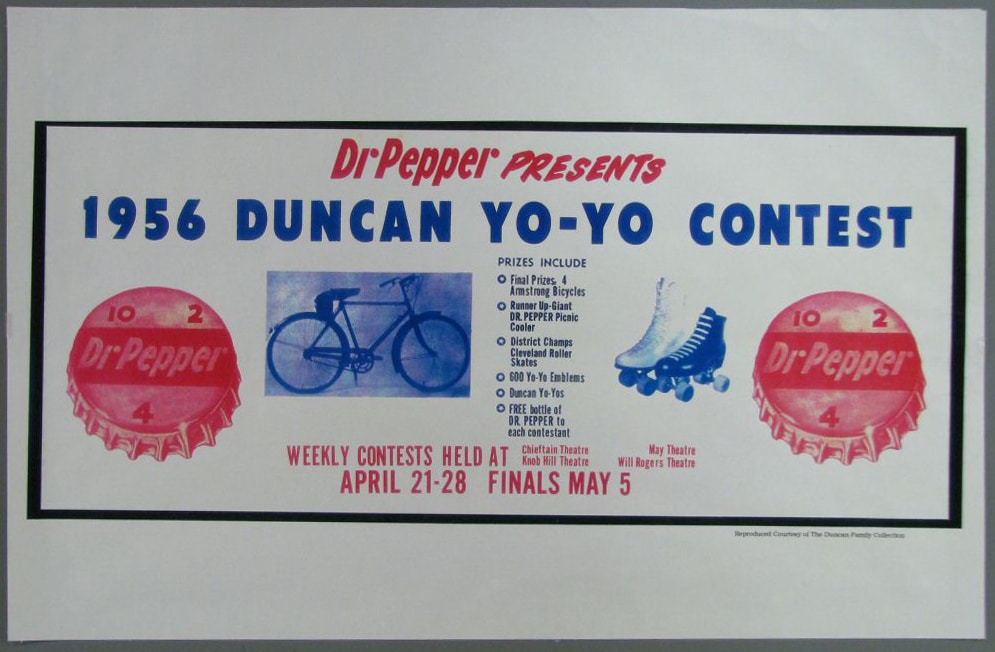

The strict parochial grade school I attended in the 1960s banned the yo-yo. It marked its owner as an idler who’d been lured astray. The Duncan slogan, a mantra almost, may have sounded like a rival liturgy too: “if it isn’t a Duncan, it isn’t a yo-yo, if it isn’t a Duncan, it isn’t a yo-yo….” Naturally, playing with the yo-yo at school took on the flavor of an outlawed pleasure.

During the baby boom, playgrounds were parking lots, and during recess in those years, the crowded asphalt, like kids’ play itself, became mostly kids’ territory. But still, the authorities could invade and confiscate a yo-yo if they discovered one. Once seized, the toy would be whirled and flung onto the school’s flat roof, ritually sacrificed. In my memory, this smooth move has merged with martial-arts movie choreography; it’s no longer possible to retrieve the moving image of the swirling black-and-white habit of the Dominican nun without also thinking of the kung-fu robes of the Shaolin priest.

During the baby boom, playgrounds were parking lots, and during recess in those years, the crowded asphalt, like kids’ play itself, became mostly kids’ territory. But still, the authorities could invade and confiscate a yo-yo if they discovered one. Once seized, the toy would be whirled and flung onto the school’s flat roof, ritually sacrificed. In my memory, this smooth move has merged with martial-arts movie choreography; it’s no longer possible to retrieve the moving image of the swirling black-and-white habit of the Dominican nun without also thinking of the kung-fu robes of the Shaolin priest.

Did this really happen? Now, I can’t say for certain. But I am sure we students imagined that a shining surface festooned with gleaming transparent Imperials waited above. The roof would be ankle deep in multi-colored Mardi Gras yo-yos, sleek black Tournaments too, and wooden spaceship-shaped Satellites that whistled. It was a field of dreams.

A version of this blog first appeared in Ed and Woody Sobey, The Way Toys Work (2008).

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.