I came to The Strong Museum to study Carmen Sandiego, the shadowy villain who stars in one of the most successful educational game series in video game history, but I left knowing a lot more about the early days of the educational game industry.

I am a Latinx literature scholar and lifelong gamer, whose research has been focused primarily on AfroLatinx literature and culture (my first book came out in June 2024). My research on Miles Morales and the Latino legacy of Spider-Man has been part of the journey to my second book project, which is currently titled Gaming Latinidad.

Being at The Strong has made me rethink aspects of my first book—it’s really clear to me how MUCH my love of play and the study of play influenced my approach to AfroLatinx life writing in Invisibility and Influence and how that book so seamlessly led to my game studies research. From my introduction (which focuses on Veronica Chambers’ use of Double Dutch jump rope in Mama’s Girl as a metaphor for her Afro-Panamanian girlhood) to my book’s final chapter (which examines Ariana Brown’s and Jaquira Díaz’s AfroLatinx girlhood), play invades nearly every chapter. I examine the playful, yet taut tension, of “the dozens” in Piri Thomas’s exploration of AfroLatinidad. My chapter on Marta Moreno Vega’s memoirs and a short autobiographical essay by Lourdes Casal is all about a concept of AfroLatinidad that focuses on the playful interaction, rather than competition, between Blackness and Latinidad. Even in my discussion of the under-researched work of Pura Belpré, I am drawn to her folklore and writing for children of color, areas that haven’t been viewed as sufficiently scholarly or “serious.” It was too play-centered.

This brings me back to Carmen Sandiego and my current book project, Gaming Latinidad. While I originally thought a love for thinking about medium and genre tied my first and second book projects together, I think both are truly united by thinking about play. And “Play” is having a wonderful surge in scholarship. In particular, thinking about race, play, and identity can lead to many different conclusions, whether it is the Black phenomenological approach of Aaron Trammel in Repairing Play and Privileged Play, to the feminist approach of Shira Chess and Amanda Phillips, to queer game studies and Black game studies, and beyond. Kishonna L. Gray in Intersectional Tech and Arayol Prater, a researcher of Black Play and Culture at The Strong, are concerned with how objects are played with and the context of that play. Again, I think of the Double Dutch rope, which Prater so beautifully contextualizes in his Strong blog post, “Toyetic Oppression”—after all, it’s just a couple jump ropes, if you don’t present them without the cultural and gendered context of Double Dutch.

And in many ways, CONTEXT was the major takeaway from my hours spent in the Brian Sutton-Smith Library Reading Room. I learned more about the emergence of software companies and the specialization of companies into “game companies.” By exploring the Brøderbund and Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium/Corporation (MECC) collections, I saw the stunning changes that occurred in the software industry from their beginnings in the 1970s and early 80s to their unceremonious ends in the late 1990s. In addition, in watching media coverage preserved in the 1up Games media collection in the early 2000s, I feel like I better understand three decades of gaming history.

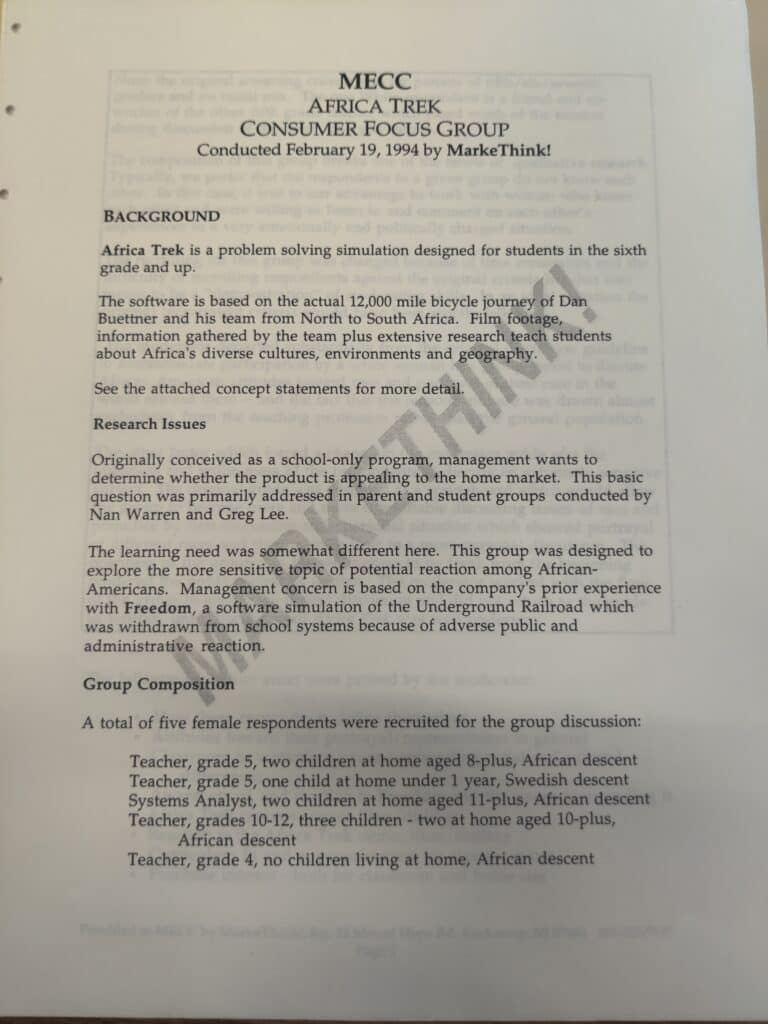

One aspect that drew my attention as a scholar of race and ethnicity was the incredibly limited attention to race and ethnicity in media coverage and marketing research within this time period. Both Brøderbund and MECC didn’t really consider ethno-race (like people who identify their ethnic background as Hispanic [or non-Hispanic] and their race as Black, Asian, White, etc.) as a category worth tracking. The only major exception to this was when they were afraid of a potential controversy. In the MECC collection, I found a focus group report on a game called Africa Trek (officially published as Africa Trail) that brought together a handful of Black participants (and one white participant) to provide feedback to avoid the controversy that embroiled the earlier MECC game Freedom!, leading to the game being pulled from the MECC catalog. Of course, no other focus groups for MECC considered racial or ethnic identity, and I found that even market research surveys sent by both Brøderbund and MECC never asked for ethno-racial identity. I certainly grew to appreciate how much things have changed so that groups like the Entertainment Software Association (ESA) now collect much more data on the identities of gamers and game developers alike.

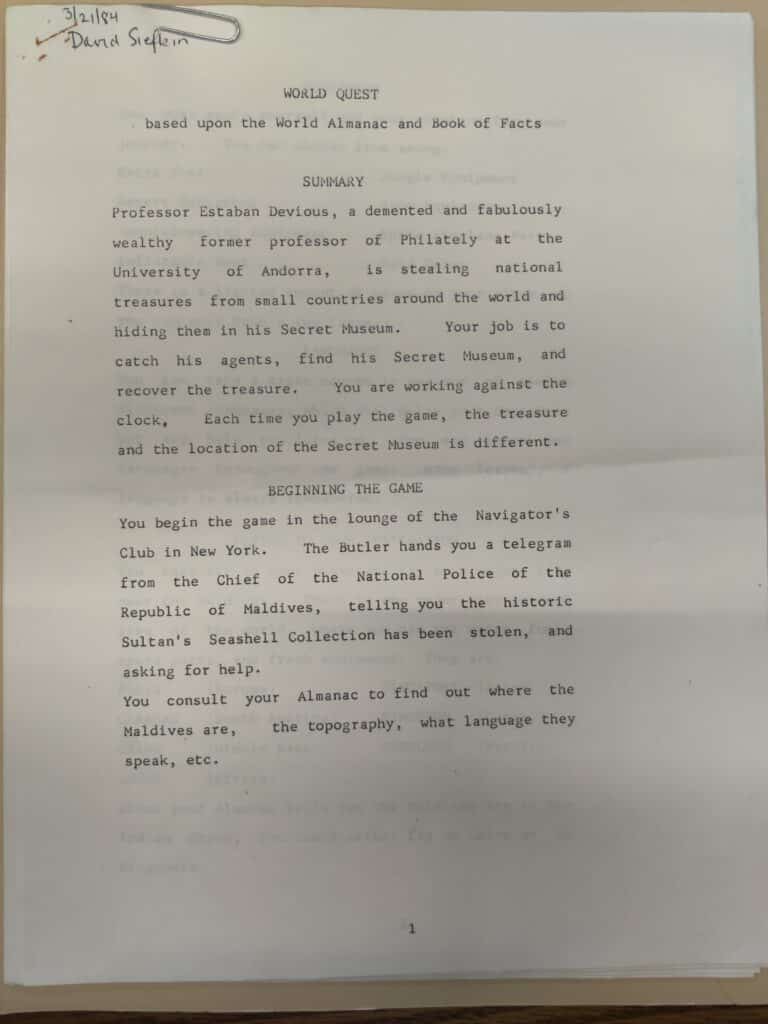

This lack of ethno-racial category data has been a major difficultly in my research, and it feeds the common idea that there are few people of color who develop or play games. And this is why Carmen Sandiego, a character I grew to love as a child who watched the Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego? game show in the 1990s, has been a bit of an obsession for me. Carmen has never really been a fully developed character (as most villains in video games aren’t). But she is also one of only a few that, based on name alone, a girl might see as Hispanic/Latina. The history I learned about Carmen at The Strong just further complicates it. First, I found the origins of Carmen Sandiego —“she” was supposed to be a “he”: a male villain named Estaban Devious (of Andorra; first name misspelled to have two A’s). One of the most significant discussions of Carmen Sandiego can be found in David L. Craddock’s Break Out: How the Apple II Launched the PC Gaming Revolution (2017), which I read at The Strong.

In Break Out, interviews claim that Carmen Sandiego is not actually Hispanic. Gary Carlston asserts, “We came up with a back story about her maiden name being something Swedish to deflect concern about her being a bad role model for Hispanic girls.” However, this history doesn’t exist in the archival documents, where there is no discussion of making her Hispanic or Swedish or having a maiden name. In fact, most of the discussion is about a reluctance to make more Carmen games despite their wild popularity.

That makes one question: is Carmen Sandiego Swedish? Hispanic? Or just an “exotic” symbol with no past that can appeal to the “any girl?” At the same time, if she’s not Hispanic, then why was Gina Rodriguez so obsessed with her that she spearheaded a revival of the character on Netflix (2019-2021, 4 seasons) which aimed to provide her a true backstory, solidifying her Latin American heritage (Argentinian, to be specific)? The main theme in that show (which is great, by the way) is that Carmen is misunderstood on all sides—by the ACME agents and by the villain organization VILE. She is an orphan who doesn’t know who she is, but that everyone else wants to use for their advantage. The Carmen Sandiego whose face is always shadowed by her red fedora has been projected on, for good and for ill.

I know there is so much more to learn about Carmen Sandiego and the Latinx legacy of video games. I wasn’t sure what, if anything, I would find at The Strong. I am so glad I came with enthusiasm and an open mind. While there might be a dearth of records on the very real presence of Black and white Latinos, Latinas, and Latinxs in video games, I continue to find our history in the gaps.

By Regina Marie Mills, Strong Research Fellow (Summer 2024)