Domestic hobbies scratch the play itch—the need for creative expression and for losing yourself in the flow of an activity. In my previous blog, I addressed the therapeutic nature of crafting and the calm that it brings to its practitioners. Creative pursuits can also meet the need for community, for comfort and companionship for the individual and also for the comfort of the greater good, through social causes and charities.

Limited in the roles they could play outside of the home, American women of the past often suffered from loneliness as well as from the physically exhausting work of caring for their families in an agricultural society. Isolation often greeted them at the end of their journeys during the Western Expansion of the 1840s, as they left friends and families behind. In more urban areas, the Industrial Revolution sharply divided men’s and women’s work as men left the home to work in factories and women stayed home to manage the household. Sewing circles, quilting bees, and communal gardening and canning helped meet women’s needs for companionship and were seen as “acceptable” pursuits. Skills and techniques were taught, materials and advice were shared, and women were given a voice at these gatherings that they did not necessarily have at home. “Women could share their anxieties without being told that their concerns were trifling; here they could communally affirm women’s view of the world and, perhaps, even attack male society,” writes Marilyn Ferris Motz in Making of the American Home: Middle-Class Women and Domestic Material Culture, 1840–1940.

Eventually, these gatherings and the resulting companionship inspired the participants to look beyond their small, “tightly knit” circles. The Fragment Society was formed in 1812 with the mission to clothe destitute women and children in Boston. In its first year, the society’s membership reached 584 wealthy and middle class women who provided 3,706 articles of clothing, blankets, diapers, and other necessities to 506 needy families. The Fragment Society recently celebrated its 200th anniversary, making it the oldest continuous sewing circle in the country.

Eventually, these gatherings and the resulting companionship inspired the participants to look beyond their small, “tightly knit” circles. The Fragment Society was formed in 1812 with the mission to clothe destitute women and children in Boston. In its first year, the society’s membership reached 584 wealthy and middle class women who provided 3,706 articles of clothing, blankets, diapers, and other necessities to 506 needy families. The Fragment Society recently celebrated its 200th anniversary, making it the oldest continuous sewing circle in the country.

Anti-Slavery Sewing Circles were common preceding the Civil War. The December 3, 1847 issue of The Liberator, edited by abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, featured a plea for the formation of more such organizations. “Sewing Circles are among the best means for agitating and keeping alive the question of anti-slavery. … Some one of the members generally reads an anti-slavery book or paper to the others during the meeting, and thus some who don’t get a great deal of anti-slavery at home have an opportunity of hearing of it at the circle.”

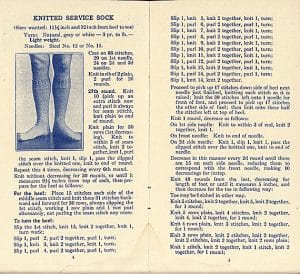

Combating slavery was not the first cause that inspired strategy application of crafts. American women had been supporting the cause of liberty since the Revolutionary War. Their weaving skills were called into service in the effort to boycott expensive (and heavily taxed) British cloth and use American-made, homespun material for clothing and household linens. “Spinning bees” throughout New England brought women together to perform their craft as a group. Similarly, wives and mothers heeded the soldiers’ cry of “send socks!” during the Civil War, knitting mittens, scarves, and socks by the score for their men in blue or gray. The forerunner to the Red Cross, the United States Sanitary Commission, was formed in 1861 in order to coordinate the production and distribution of knitted goods and medical supplies in the North. A half-century later, the Red Cross coordinated the American “war knitting” effort in 1917 when the United States entered the First World War. The November 24, 1941, cover story of Life magazine detailed how America’s knitters could use their skills help the war effort during World War II. The article also hoped to provide a modicum of quality control for those enthusiastic—but less skilled—knitters.

Combating slavery was not the first cause that inspired strategy application of crafts. American women had been supporting the cause of liberty since the Revolutionary War. Their weaving skills were called into service in the effort to boycott expensive (and heavily taxed) British cloth and use American-made, homespun material for clothing and household linens. “Spinning bees” throughout New England brought women together to perform their craft as a group. Similarly, wives and mothers heeded the soldiers’ cry of “send socks!” during the Civil War, knitting mittens, scarves, and socks by the score for their men in blue or gray. The forerunner to the Red Cross, the United States Sanitary Commission, was formed in 1861 in order to coordinate the production and distribution of knitted goods and medical supplies in the North. A half-century later, the Red Cross coordinated the American “war knitting” effort in 1917 when the United States entered the First World War. The November 24, 1941, cover story of Life magazine detailed how America’s knitters could use their skills help the war effort during World War II. The article also hoped to provide a modicum of quality control for those enthusiastic—but less skilled—knitters.

“Craftivism,” a term coined by Betsy Greer to mean “the practice of engaged creativity, especially regarding political or social causes” can be used to describe the current iteration of America’s long history of crafting for a cause. Greer’s 2014 book, Craftivism: The Art of Craft and Activism, profiles artists all over the world who are using their creative skills—from knitting to pottery—to further a cause or raise awareness.

“Craftivism,” a term coined by Betsy Greer to mean “the practice of engaged creativity, especially regarding political or social causes” can be used to describe the current iteration of America’s long history of crafting for a cause. Greer’s 2014 book, Craftivism: The Art of Craft and Activism, profiles artists all over the world who are using their creative skills—from knitting to pottery—to further a cause or raise awareness.

For those looking to take their hobby beyond their living room or small group of friends, a quick search online will yield dozens of opportunities to knit hats for cancer patients and premature infants, sew dresses for children in Africa, and make blankets for children in foster care or for animals awaiting adoption in shelters. Domestic hobbies can connect you communities down the street or across the globe.

This is Part Three in Beth Merkle’s Domestic Hobbies series.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.