“I knit so I don’t kill people.”

You can buy a mug, a tote bag, or a shirt with this phrase emblazoned on it. You can meet a handful of fellow knitters out on the town for World Wide Knit in Public Day or you can share your projects and patterns with the 5.5 million registered users of Ravelry, the social media site for knitters and crocheters. Surprised? You shouldn’t be: knitting, along with other “domestic hobbies,” is exceedingly popular, and has never really gone out of style.

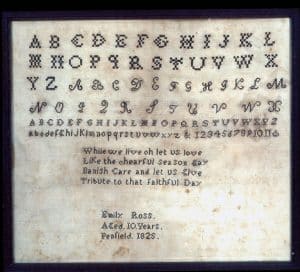

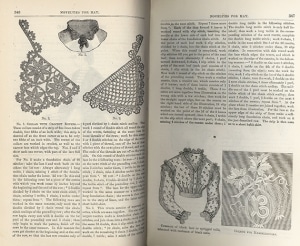

Knitting, sewing, crocheting, needle point, cross stitch, embroidery, quilting, scrapbooking, crafting, building miniatures and doll houses, vegetable gardening, canning and preserving—all traditionally viewed (and often dismissed) by society as “women’s work”—are thriving in today’s do-it-yourself culture. The modern feminist movement of the latter 20th century and the normalization of women in the workplace were assumed to be the death knell for domestic hobbies (and domesticity in general). If women were no longer expected to dedicate all of their energy to creating a tranquil home environment for their husbands and children, then surely they would turn away from the drudgery of hand-stitching samplers. We picture oppressed Victorian ladies hunched over their needlepoint and can’t imagine that there is a place for such an activity in our modern, technology-driven world.

Knitting, sewing, crocheting, needle point, cross stitch, embroidery, quilting, scrapbooking, crafting, building miniatures and doll houses, vegetable gardening, canning and preserving—all traditionally viewed (and often dismissed) by society as “women’s work”—are thriving in today’s do-it-yourself culture. The modern feminist movement of the latter 20th century and the normalization of women in the workplace were assumed to be the death knell for domestic hobbies (and domesticity in general). If women were no longer expected to dedicate all of their energy to creating a tranquil home environment for their husbands and children, then surely they would turn away from the drudgery of hand-stitching samplers. We picture oppressed Victorian ladies hunched over their needlepoint and can’t imagine that there is a place for such an activity in our modern, technology-driven world.

But that mellow mother of two in the cubicle next to you might just be knitting so she doesn’t kill you (not literally, of course). The knitters, quilters, and crafters of today say that their hobby has a therapeutic effect, calming them when they feel overwhelmed. The repetitive motion, attention to detail, and feel of their chosen medium in their hands helps them relax and de-stress after long days at the office or at home, chauffeuring children and coordinating calendars. The explosion in popularity of coloring books for adults is further testimony to how much we as a society crave the calmness that working with our hands can bring.

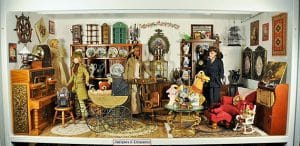

Julie Conner, a modern wife and mother, created miniature rooms to bring calm to her life. She hand-selected and placed each piece, often working late at night when her house was quiet. She found creating miniature rooms to be a sort of “play-therapy” during a difficult time in her life, soon after her toddler son was diagnosed with autism. She donated 28 of her miniature rooms to The Strong in 2014 and they stand not only as playful art, but also as testimony to the healing power of play. And you can see eight examples of her rooms displayed in Build, Drive, Go on the museum’s second floor.

Julie Conner, a modern wife and mother, created miniature rooms to bring calm to her life. She hand-selected and placed each piece, often working late at night when her house was quiet. She found creating miniature rooms to be a sort of “play-therapy” during a difficult time in her life, soon after her toddler son was diagnosed with autism. She donated 28 of her miniature rooms to The Strong in 2014 and they stand not only as playful art, but also as testimony to the healing power of play. And you can see eight examples of her rooms displayed in Build, Drive, Go on the museum’s second floor.

The rural, Midwestern housewife of the last century reaped the same emotional healing from her “fancywork.” In Making of the American Home: Middle-Class Women and Domestic Material Culture, 1840-1940, Marilyn Ferris Motz writes, that “fancywork provided women with a means of creative expression that was compatible with socially accepted roles for middle-class women but also allowed for a limited transcendence of those roles through a temporary escape into fantasy and a whimsical transformation of mundane objects into fanciful ones.” Their handiwork allowed them to create order out of the chaos of their daily lives, even when they felt helpless to the whims of Mother Nature and patriarchal society.

The rural, Midwestern housewife of the last century reaped the same emotional healing from her “fancywork.” In Making of the American Home: Middle-Class Women and Domestic Material Culture, 1840-1940, Marilyn Ferris Motz writes, that “fancywork provided women with a means of creative expression that was compatible with socially accepted roles for middle-class women but also allowed for a limited transcendence of those roles through a temporary escape into fantasy and a whimsical transformation of mundane objects into fanciful ones.” Their handiwork allowed them to create order out of the chaos of their daily lives, even when they felt helpless to the whims of Mother Nature and patriarchal society.

Domestic hobbies, from knitting to crafting elaborate miniature rooms, satisfy many people’s need for creative expression, and have done so for centuries. The calm attained when lost in the flow of an activity is a powerful and addictive, and a welcome respite from the worries of everyday life.

This is Part One in Beth Merkle’s Domestic Hobbies series.