Knitting, quilting, and other domestic hobbies appear to have experienced a surge in popularity over the past two decades. Perhaps it is more accurate to state that they have experienced a surge in visibility thanks to social media and other online communities, as the qualities that attract people to domestic hobbies have remained constant for centuries. In previous posts, I addressed their therapeutic benefits and ability to create a sense of community among crafters. There is a third reason why domestic hobbies have stood the test of time, a reason closer to our hearts than to our hands: these creative pursuits simultaneously allow us to honor our past and ensure our legacy in the future.

The warm feeling of kinship crafters feel is not just toward fellow crafters, who enjoy the same hobby. Many people learned a craft at the knee of a beloved parent, grandparent, aunt, or uncle who has since passed away. The act of crafting stirs up childhood memories and serves as a tribute to our ancestors. A friend of mine gardens because it reminds her of her grandfather and of all the lessons he taught her in his garden. Another learned woodworking from his grandfather and took it up again in his 30s, after he became a parent. My stepmother and I inherited our mothers’ fabric stashes and sewing machines. When we use the skills, materials, and equipment they gave us, we are assured that they are still with us, and our finished projects feel like tributes to their lives and our relationships.

The warm feeling of kinship crafters feel is not just toward fellow crafters, who enjoy the same hobby. Many people learned a craft at the knee of a beloved parent, grandparent, aunt, or uncle who has since passed away. The act of crafting stirs up childhood memories and serves as a tribute to our ancestors. A friend of mine gardens because it reminds her of her grandfather and of all the lessons he taught her in his garden. Another learned woodworking from his grandfather and took it up again in his 30s, after he became a parent. My stepmother and I inherited our mothers’ fabric stashes and sewing machines. When we use the skills, materials, and equipment they gave us, we are assured that they are still with us, and our finished projects feel like tributes to their lives and our relationships.

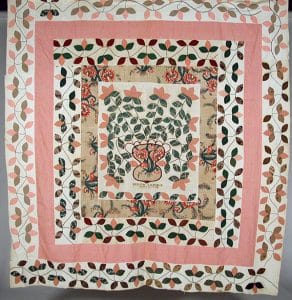

Permanence is another recurring theme in the world of domestic hobbies. Often women are busy all day but have nothing to show for it when the sun sets. A modern woman will have driven her children back and forth from activities following her own commute to and from work, cooked an entire meal, washed laundry, cleaned dishes, and more before heading to bed, only to get up and do it all over again. Her ancestors would have done the same, minus modern conveniences and commuting. Where is the proof that she was here? That she had done well for herself and her family? A woman interviewed for No Idle Hands: the Social History of American Knitting by Anne L. Macdonald, published in 1988, summed up her hobby this way: “I knit mainly for the satisfaction of accomplishment. Since, in my thirty-odd years as a full-time homemaker, I expended such an enormous amount of energy merely to maintain the status quo with the same work still there to be done again the next day that it was so satisfactory to spend even a few minutes doing something that didn’t need to be done again!” Or, in the words of the narrator from Eliza Calvert Hall’s novel, Aunt Jane of Kentucky (1907), “When I’m dead and gone there ain’t anybody goin’ to think o’ the floors I’ve swept, and the tables I’ve scrubbed, and the old clothes I’ve patched, and the stockin’s I’ve darned…. But when one o’ my grandchildren or great-grandchildren seen one o’ these quilts, they’ll think about Aunt Jane, and, wherever I am then, I’ll know I ain’t forgotten.”

Permanence is another recurring theme in the world of domestic hobbies. Often women are busy all day but have nothing to show for it when the sun sets. A modern woman will have driven her children back and forth from activities following her own commute to and from work, cooked an entire meal, washed laundry, cleaned dishes, and more before heading to bed, only to get up and do it all over again. Her ancestors would have done the same, minus modern conveniences and commuting. Where is the proof that she was here? That she had done well for herself and her family? A woman interviewed for No Idle Hands: the Social History of American Knitting by Anne L. Macdonald, published in 1988, summed up her hobby this way: “I knit mainly for the satisfaction of accomplishment. Since, in my thirty-odd years as a full-time homemaker, I expended such an enormous amount of energy merely to maintain the status quo with the same work still there to be done again the next day that it was so satisfactory to spend even a few minutes doing something that didn’t need to be done again!” Or, in the words of the narrator from Eliza Calvert Hall’s novel, Aunt Jane of Kentucky (1907), “When I’m dead and gone there ain’t anybody goin’ to think o’ the floors I’ve swept, and the tables I’ve scrubbed, and the old clothes I’ve patched, and the stockin’s I’ve darned…. But when one o’ my grandchildren or great-grandchildren seen one o’ these quilts, they’ll think about Aunt Jane, and, wherever I am then, I’ll know I ain’t forgotten.”

The finished products of domestic hobbies serve as more than just some kind of “I was here” graffiti. Often lives are quite literally woven into the fabric of a quilt. In America’s Quilts and Coverlets by Carleton L. Safford and Robert Bishop, Marguerite Ickis quotes her great-grandmother while describing the patchwork quilt she made that is now a family heirloom: “My whole life is in that quilt. It scares me sometimes when I look at it. All my joys and all my sorrows are stitched into those little pieces…. I tremble sometimes when I remember what that quilt knows about me.” Domestic hobbies are calming, communal, and continuously popular across the generations. They make people feel relaxed and accomplished. But perhaps their real magic lies in their ability to be both a testimony and a legacy; these objects we create are an assurance that we were here and will be here for a long time to come.

This is Part Two in Beth Merkle’s Domestic Hobbies series.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.