Play begins in anticipation. This is true not only for play generally but also specifically for video games. We discover a game from an advertisement or through word of mouth or perhaps from reading or watching something that someone else—often a professional journalist—has written or produced about the game. We begin to daydream about the game and think about what we’ll do in it, what surprises we’ll discover, and what challenges we will have to overcome. Our fingers itch to type on the keyboard or handle the controller that will bring this world to life.

Today we learn about video games from a multitude of sources: YouTube, social media, web sites, forums, direct-to-consumer presentations from companies, and even sometimes print magazines. Only a handful of game magazines are still published, but before the advent of the internet, paper magazines like Margot Comstock’s Softalk were the best sources of information for what was new and notable in the world of electronic gaming. Like everything else, video game journalism has a history, and David Ahl, founder of Creative Computing, has an outsized role in that early history.

For most people in the early 1970s, computers were more common in imaginary worlds than in real life. Movies like 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)—featuring Hal 9000, a computer that played chess but also sought to destroy its human overlord—held out the possibility of incredibly powerful computers that would transform life. In reality, the only people who interacted with computers regularly were those in computer labs who used multi-terminal devices like hulking mainframes or the recently developed minicomputers. These were serious machines for serious people doing serious work.

David Ahl began working with computers in the 1960s and then joined the Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) as Education Product Line Manager. DEC was a leader in the field of minicomputers, networked computers that while less powerful than the massive mainframes that companies like IBM produced, were still powerful machines that could operate many terminals. At DEC in 1971 he started a newsletter called EDU that served the educational community, but he soon realized that there was a need for publications that could reach wider audiences.

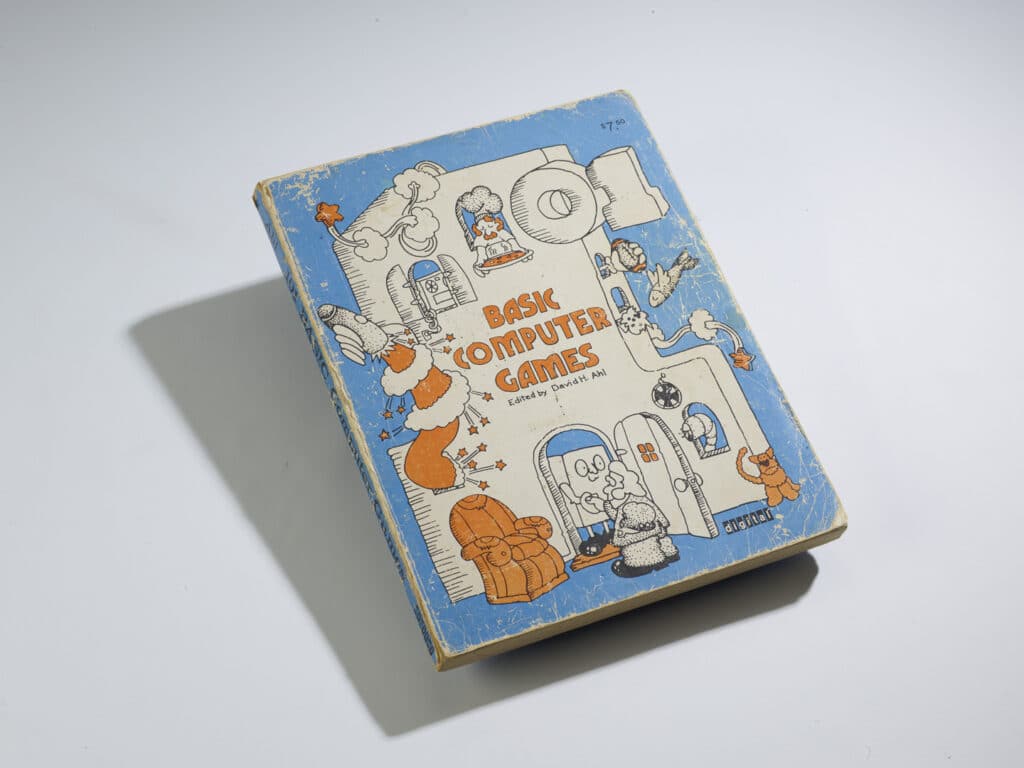

Ahl’s first general interest publication was a book, 101 BASIC Computer Games, that he released in 1973. In the preface he acknowledged that itwas not the first book of computer games, but he pointed out that it was the first one with games all in BASIC (the most accessible programming language). He noted that, “The games in this book were collected on my travels to schools as well as from submittals in response to an advertisement in EDU, a newsletter published by Digital Equipment Corporation. Game authors range from seventh graders in Massachusetts and California to PhDs in England and Canada.” (As a personal aside, I received a later edition of the book in the early 1980s and it helped teach me to program).

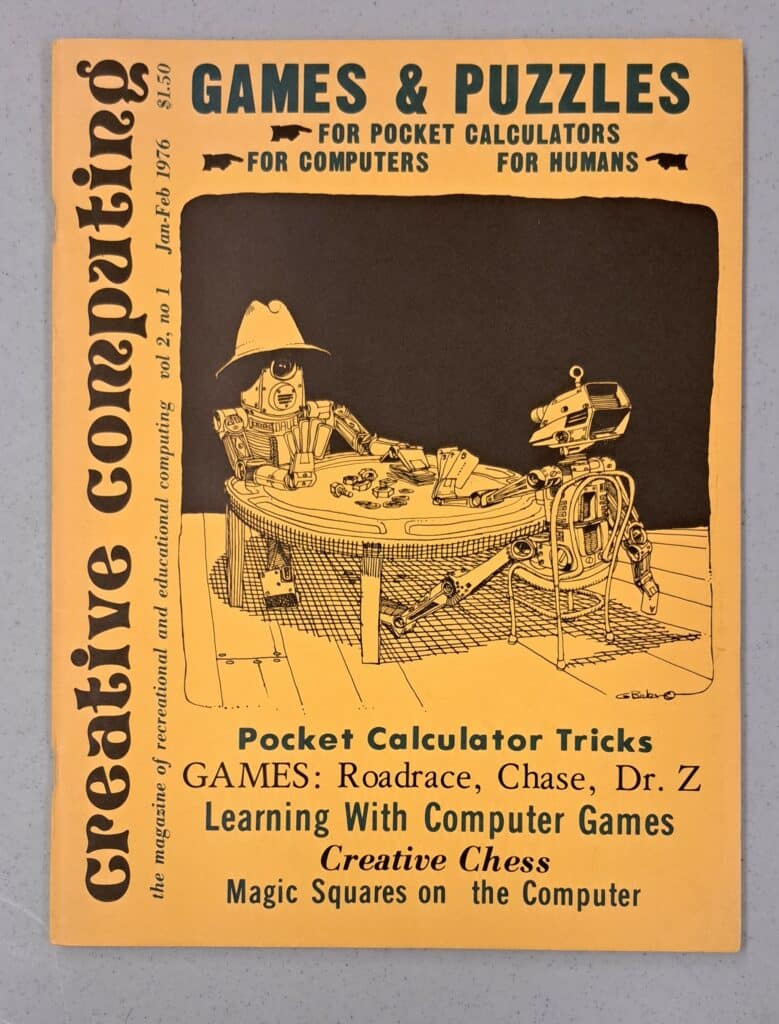

While publishing his book he also was working on the idea for a magazine, Creative Computing. Ahl pursued foundation and corporate support but in the end launched the magazine on his own. It debuted in October of 1974. The magazine covered a wide array of uses of computers, though he focused generally on the creative and playful possibilities of digital machines. Creative Computing was initially subtitled “The Magazine of Recreational and Educational Computing” and Ahl included fiction, jokes, cartoons, simulations, and puzzles. He especially liked articles on computer art, showing a special fondness for using computers to print Star Trek characters.

But people especially wanted to learn about games at a time when most computer users were isolated from each other and so had a hard time learning about or gaining access to games. One Minnesota correspondent wrote in a letter to the editor in the inaugural issue in 1974, “Would you please send me information about the games you can play on computers? If you would I would appreciate it alot [sic].” Going through back issues of the magazines in The Strong’s collection reveals that games were indeed a prominent feature of Creative Computing. Sometimes articles brought attention to commercial releases—an article on “How to Beat Pong” in the May-June 1975 issue is perhaps the first guide to video games ever published—but more often the essays provided not only descriptions of games that individuals had created, but the accompanying code in the BASIC programming language so users could type the software in themselves.

Most of the people writing these games came from colleges and universities, but some hailed from other places like science museums or even secondary schools. Jim Storer, for example, after watching the Apollo moon landing was inspired in the fall of 1969 (the magazine attributed it to the mid-1960s) to write a program to simulate the landing of a rocket on the moon’s surface. The program was remarkable, doubly so because Storer was a high school student from Lexington, Massachusetts. It appeared in the same issue as the “How to Beat Pong” article.

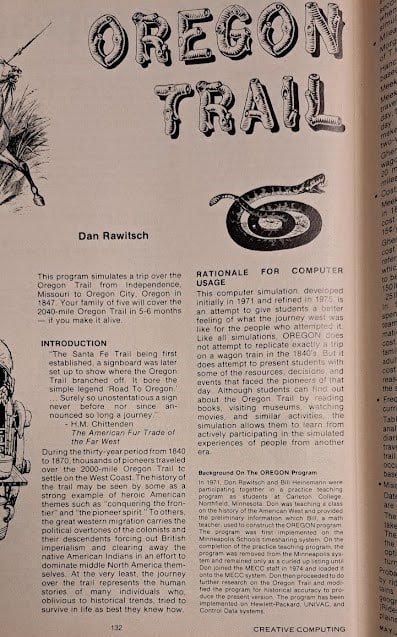

Another famous game, Oregon Trail, also appeared in Creative Computing, in the May-June 1978 issue. Written by the game’s creator, Don Rawitsch, the article not only provides the game’s code and a sample run but also background on the development of the game and the historical documents that undergirded the program’s modeling of hazards and rewards on the trip. What is also interesting, given some recent criticisms of the game as inherently colonialist, is that Rawitsch acknowledges upfront the fraught history of the subject, noting:

“The history of the trail may be seen by some as a strong example of heroic American themes such as “conquering the frontier” and “the pioneer spirit.” To others, the great western migration carries the political overtones of the colonists and their descendants forcing out British imperialism and clearing away the native American Indians in an effort to dominate middle North America themselves.”

Giving creators room to talk about their games, explain their purposes and reveal their goals in creating them, is one of the special things about Creative Computing. It was a thoughtful magazine.

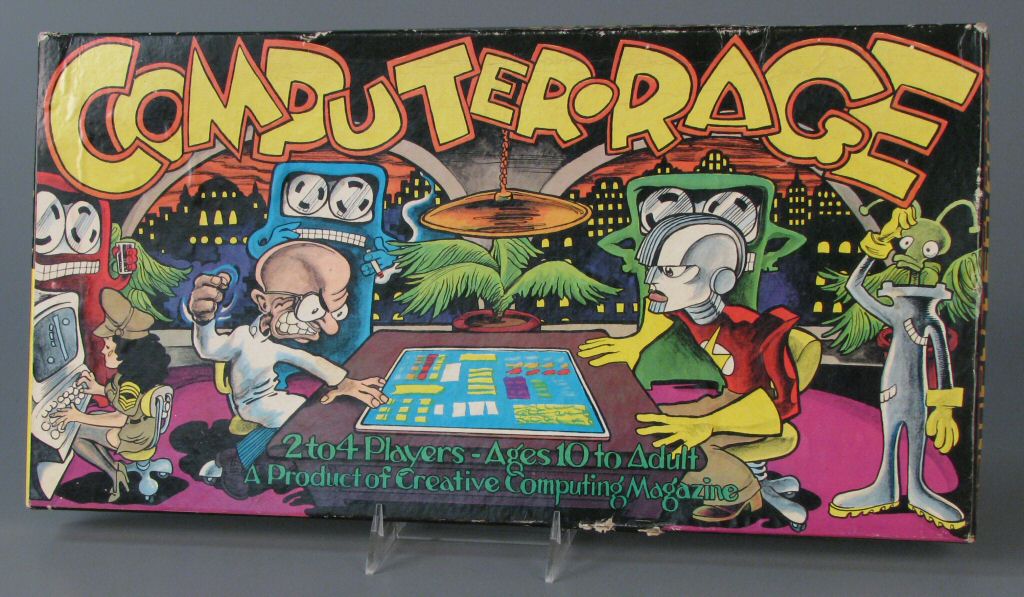

As the magazine became more successful, Ahl repurposed many of the articles he published into more books. He even produced a board game, Computer*Rage, that challenged players to race from input to output in a simulated computer environment. A board game simulation of a computer game… that’s just the sort of out-of-the-game-box thinking that prompt Ahl to launch Creative Computing in the first place, inspire others to found computer magazines, and spur people to find new ways to play with computers.