The next time someone criticizes video games for their impact on moral values, here’s some historical perspective to offer them.

More than 200 years ago, commentators expressed concern that the newly popularized novels distracted readers from their work and harmed their morals. Critics worried especially about young women who became some of the most avid fans of novels. In an 1802 broadside, “Novel Reading, a Cause of Female Depravity,” one critic wrote, “Without the poison instilled [by novels] into the blood, females…would never have been so much the slaves of vice….” A year later, Samuel Miller, a member of the American Philosophical Society, warned:

“Every opportunity is taken [in novels] to attack some principle of morality under the title of a “prejudice;” to ridicule the duties of domestic life, as flowing from “contracted” and “slavish” views; to deny the sober pursuits of upright industry as “dull” and “spiritless;” and, in a word, to frame an apology for suicide, adultery, prostitution, and the indulgence of every propensity for which a corrupt heart can plead an inclination….”

By the late 19th century, critics resigned themselves to most novels but instead fretted about the popularity of a new type of inexpensive, action-packed adventure story known as the dime novel. These books, many commentators said, might spoil youth for steady work and ruin their chances for a lasting marriage. United States Postal Inspector Anthony Comstock first sounded the alarm in his 1883 book Traps for the Young, in which he wrote, “These stories breed vulgarity, profanity, loose ideas of life, impurity of thought and deed. They render the imagination unclean, destroy domestic peace, desolate homes, cheapen a woman’s virtue, and make foul-mouthed bullies, cheats, vagabonds, thieves, desperadoes, and libertines. They disparage honest toil, and make real life a drudge and burden.”

During the following decade, critics targeted the newly popularized juvenile series books, like The Hardy Boys. In 1914 Franklin K. Mathiews published an overwrought critique in the prominent magazine Outlook entitled “Blowing Out the Boy’s Brains.” He claimed, “The chief trouble with these books is their gross exaggeration, which works on a boy’s mind in as deadly a fashion as liquor will attack a man’s brain.”

Some of Americans’ most hysterical reactions to new media came in the baby boom era, when comic books and rock’ n’ roll transformed popular culture.

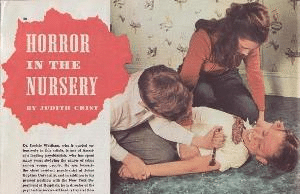

Comic books, especially horror comics, came under particularly severe attack. Frederick Wertham, a prominent psychologist, charged that these incited violence. In a 1948 Reader’s Digest article, he asserted, “Think of the many violent crimes committed recently by young boys and girls…. The common denominator is comic books.” And in his 1954 book, Seduction of the Innocent, he cautioned, “The role of comic books in delinquency is not the whole nor by any means the worst harm they do to children. It is just one part of it. Many children who never become delinquent or conspicuously disturbed have been adversely affected by them.”

Of rock and roll, Joost Meerlo, another well-known psychologist, noted in 1957 that, “Rock’ n’ roll is a sign of depersonalization of the individual, of ecstatic veneration of mental decline and passivity. If we cannot stem the tide with its waves of rhythmic narcosis and of future waves of vicarious craze, we are preparing our own downfall in the midst of pandemic funeral dances.”

Just as doomsayers predicted that crime waves and moral collapse would surely follow the rise of novels two centuries ago, dime novels a century ago, and comic books and rock’ n’ roll a half-century ago, in recent years critics of video games have delivered dire warnings about video games inciting violence or making kids hyperactive. Will these sound just as silly 50 or 100 years from now?

By Jon-Paul Dyson, Director, International Center for the History of Electronic Games and Vice President for Exhibits