“The evolution of the building toy is intertwined with the developmental history of the child as builder.” Toying with Architecture: The Building Toy in the Arena of Play, 1800 to the present, 1997-1998

In August 2023, I had the privilege of two weeks of research in The Strong Museum archives, courtesy of the Valentine-Cosman Research Fellowship. This was the most family-friendly research adventure of my life. During the day, I handled precious objects in the museum archives. On Thursday, Friday, and Saturday evenings, I was able to enjoy The Strong Museum exhibits with my children.

My work in the archives “built upon” (ha!) a long-standing interest in how children inhabit and experience cities. I research children as navigators, as architects-in-training, and as city planners. I entered the fellowship having written about children’s picture books set in Harlem, and about a set of Victorian fantasy narratives that culminated in a visit to a child-friendly and eco-friendly London of the future. I am drawn to this topic for both personal and ideological reasons. I am a humanist who was raised by and among engineers, architects, and computer scientists. How can the fields engage in fruitful cross-pollinating conversations? In addition, I want to be a part of current conversations about the role children might play as advocates for greener, healthier, and more inclusive cities in the future.

At the turn of the last century, questions rose about the rural focus of many books and toys for children. What are the pedagogical implications of books and toys focused on farm life, especially as more and more children live in cities? In Aspects of Child Life and Education (1907), Granville Stanley Hall wrote, against the city, “As our methods of teaching grow natural we realize that city life is unnatural, and that those who grow up without knowing the country are defrauded of that without which childhood can never be complete or normal. On the whole, the material of the city is no doubt inferior in pedagogic value to country experience.” Hall placed the disconnects within the lived environment rather than in the pedagogical materials created for children by adults. Later artifacts, I will argue, reset or at least questioned Hall’s conclusions.

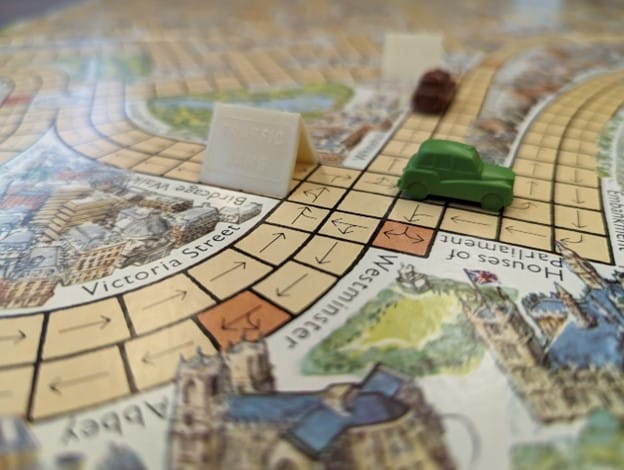

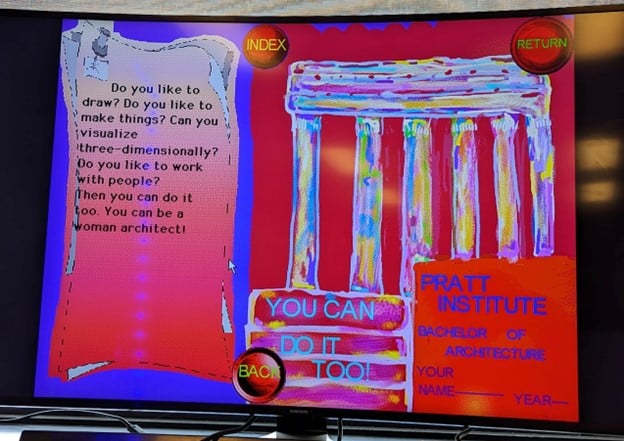

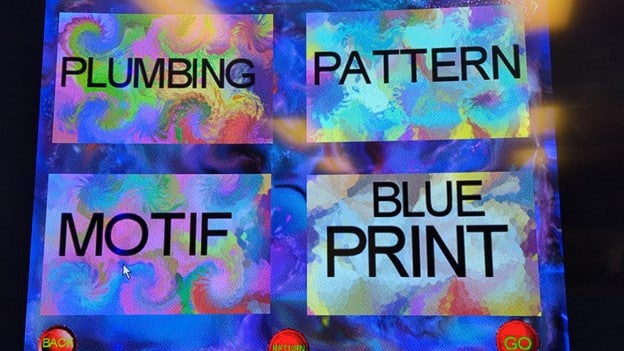

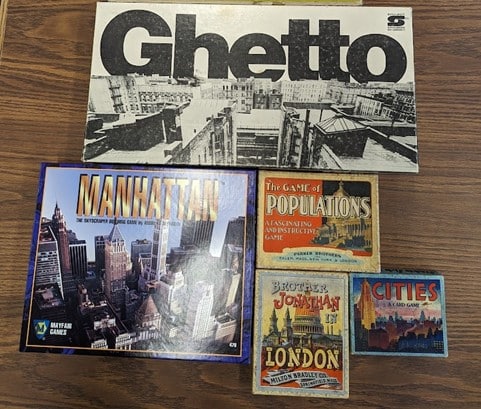

At The Strong, I examined board games that encouraged children and adults to drive in search of fares and tips (The London Cabbie Game,1971), to try their hand at city planning (Skyscraper,1937), or to survive urban poverty (Ghetto,1967). I examined the evolving marketing of architectural and building toys, from Tinker Toys and Erector sets that were aggressively marketed to boys, to a modern CD-ROM based on the children’s book You Can Be a Woman Architect (1998).

I read numerous narratives that spanned psychology, sociology, urban planning, history, and literature, all illuminating different aspects of how children learn to feel safe, creative, and empowered as builders and explorers. I learned a lot about design, marketing, health and wellness, and investigated the thin line between work and play where creating and construction is concerned. The opportunity for me, a literature scholar, to contextualize my close readings via rare specimens of material culture—ranging from a jigsaw puzzle map of Britain (1810) to unpublished interviews with Harlem schoolchildren (1960s and 1970s)—will make an enormous difference for my monograph-in-progress, Childrens Literature and the Architectural Imagination.

One category of artifact I examined at the Strong were card games and board games that taught children and adults how to navigate cities, often for “profit.” The notes, plans, marketing, and consumer feedback for the games reveal much about how different urban experiences were prioritized by game designers. For instance, Cities: A Card Game (Mayfair, 1930) offered a player the most points for capturing the largest cities, and words like “largest,” “massive,” and “most outstanding” peppered the game play cards. The pre-industrial histories of cities were either overlooked or imperially crowed about, as in this clue about New York: “This city over 300 years ago was purchased from the Indians for $24 and is now worth almost one billion times that sum.” Game of the City Traveler(McLoughlin Bros, 1880) was a Mad-Libs-style game that asked players to represent characters such as the “Yankee,” the “Turk,” the “Englishman,” the “Red Indian,” and the “African,” contributing artifacts that belong to these characters (from Patent Mouse-Traps to Cups of Green Tea) to a story about a fellow named Quiddler, who, for the first time in his life, will be traveling farther than 10 miles outside of his native city.

I went into my work in the archives knowing that the transition from 19th-century artifacts of the city to the present day would continue to involve deep engagement with race and ethnicity. For instance, in 1900 in the United States only 10% of African American people lived outside of the South, but by the end of the century many had relocated to urban centers, creating hybrids of urban life and rural farming traditions, as evidenced in Jerrilyn McGregory’s fascinating research on community gardens. In unpublished interviews from 1977, child subjects in Harlem occasionally reported a lack of commercial toys, and didn’t always understand the concept of a “hobby.” However, they found ways to play that seemed to reflect the challenges that face all in an urban ecosystem. Many documents in the collections spoke to “the problem of play, recreation, and leisure for Negro youth,” including “a problem of public attitudes and established conventions.”

It will take a while for me to unravel all implications of what I observed in The Strong’s archives. One pattern that sticks with me is the tension between creation and destruction, an appropriate analogue to Henry Petroski’s truism that “things built up only to soon come down” constitutes “the essence of all children’s construction projects.” In the Sid Sackson papers, I reviewed a pitch for a game called Urban Renewal(1972), which would have asked players to “buy slum property, demolish the existing buildings and construct new and modern high-rise buildings so profitably that one player eventually becomes the wealthiest and the winner.” The game repositioned the Monopolypremise, moving it from a thriving vacation town into a struggling, unnamed urban space. Instead of Chance and Community Chest cards, the game offered Building Permits and City Life Cards.

One unpublished piece in the Brian Sutton-Smith papers described the rules of a game called “Barnstorming,” played by a group of Harlem children in the 1970s: one child tries to build houses as quickly as she can with the materials on hand, while another child pretends to be an attacking plane, divebombing and destroying her work. Per the interviewer, “The object of the game is to try to build up your house first, without having it knocked down.” The game reminded me of a user-introduced variant on the board game Manhattan: The Skyscraper Building Game (Mayfair Games, 1995-1996). The purpose of the published game was to “compete to build the biggest and best buildings in the greatest city in the world.” Early players of the game introduced a wrinkle to gameplay that was not in the official instructions: using a household object or toy to represent a monster. In one variant, a full-grown “monster” would destroy entire buildings during game play; in another, a “baby monster” would damage existing buildings one layer at a time. Developers of that game went back and forth about whether to include the “monster” and “baby monster” variants in the commercial version of the game. (“Too loose?” one scrawled margin comment asked). In the next version of the instructions, the variants were gone. In the final version of the game, the variants had been restored. Later, published commentary suggested that the variant corrected one major flaw of game play, which is the advantage offered to the player who happened to go first. Writes the reviewer, “Give Monster Manhattan a try, it’s building-chomping fun!” That dynamic of construction and destruction at “play” seems to be an appropriate way to investigate the tenuous, ever-changing future of the city, especially in the increasingly virtual and remote post-Covid Western World.

By Melissa Jenkins, 2023 Valentine-Cosman Research Fellow