Were you one of the kids who was told that babies are found in the cabbage patch? That old folk tale gained additional resonance in the 1970s when what would become Cabbage Patch Kids dolls had their conception in rural Georgia.

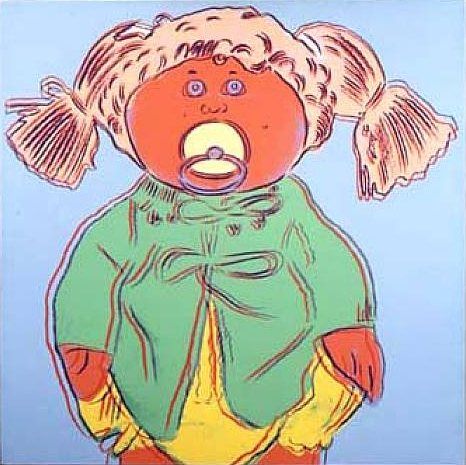

Influenced by Martha Nelson Thomas’ Doll Babies, art student Xavier Roberts combined his interest in needle molding with the quilting skills he learned from his mother to craft soft sculptures he called Little People. Roberts’ creations featured a pudgy face with close-set eyes and hair fashioned of colored yarn. They were funky rather than conventionally pretty, contrasting sharply with mass-produced plastic beauties. He dressed his homely babies in clothing picked at garage sales and gave them names he took from the 1938 birth records in his native Georgia. So far, the tale reads a bit like a storybook with a few red flags (who is Martha Nelson Thomas?), but it gets more complicated.

Roberts did not exactly “sell” Little People to customers. Instead, he offered them up for “adoption”—in return for a fee. He included a birth certificate and adoption papers with each doll. His marketing strategy proved interesting, considering that the Baby Scoop Era had come to an end. You’ve probably heard of the Baby Boom years, but the Baby Scoop Era has been defined by scholars as occupying the years following World War II through the early 1970s. During this period, an increase in out-of-wedlock pregnancies led many expecting women to adoption as the only option to navigate social expectations, poverty, illness, and family crisis. Within this social context, Roberts’ use of birth certificates and adoption papers to sell baby dolls seems completely unrelated to the feminist movement and the female experience. But the tactic proved fruitful.

Next on Roberts’ agenda was the organization of Original Appalachian Artworks, Inc. He transformed a turn-of-the-20th-century abandoned medical clinic into the company’s headquarters, and named the complex BabyLand General Hospital. Staff dressed as doctors and nurses greeted guests with southern hospitality. With national print and television media attention on his softly sculpted Little People, Roberts struggled to satisfy consumer demand.

In 1982, Original Appalachian Artworks negotiated a licensing agreement with Coleco Industries (a company founded in 1932 to make leather goods and named the Connecticut Leather Co.) to produce the dolls with vinyl (instead of soft-sculpted) heads and cloth bodies. Given that Fisher-Price already had a line of toys called the Little People, marketing wiz Roger Schlaifer renamed the dolls Cabbage Patch Kids and developed the logo and packaging. With his wife Susanne Nance, Schlaifer also double-downed on the surreal legend of the birds and the bees—or more specifically the Bunnybees and magic crystal dust. A sanitized birth story such as this fits with the history of adoption in America.

The first dolls were ready in time for the 1983 holiday season. But Coleco couldn’t keep up with the massive wave of orders. As the holiday season progressed, parents and adults became more desperate to find them for their kids. Retail stores everywhere reported disturbances as frenzied customers battled each other for the few available dolls. While adult behaviors exhibited the power of scarcity, Cabbage Patch Kids expanded children’s notions of nurture and fantasy. At the peak of their popularity, more than 2,000 products featured the Cabbage Patch Kids brand name.

For more than 40 years, the brand has intended to convey messages about unconventional beauty and belonging. As a kid, one of my favorite dolls was a bald, brown-eyed Cabbage Patch Doll marketed as a “preemie.” The appeal for me was in the doll’s baby powder scent and weighted bottom. As an adult, I find the mass-marketing of adoption, premature babies, and the consumer culture it created unsettling, but the success of Cabbage Patch Kids is undeniable.