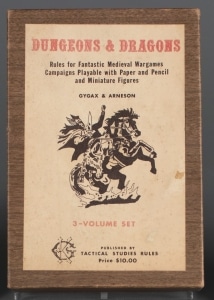

During the first few years after the introduction of Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) in 1973, Gary Gygax, who had the strongest impact on the fantasy elements of the game, denied any direct influences from fantasy author J.R.R. Tolkien. Many players recognized immediately that numerous D&D character and creature names came directly from the books. But it took until 1977 for intellectual property lawyers from a firm which had licensed the rights to Tolkien’s work to send a cease-and-desist order, at which point TSR Inc. (then known as Tactical Studies Rules) Gygax’s publishing house, famously changed the names of characters with ties to those works. Thus, in basic D&D “hobbit” became “halfling,” and “ent” became “treant.” At The Strong, we have multiple editions of the first D&D sets with Tolkien-inspired names and those that followed with synonymic names. And we have versions of another game that may have incited the change.

During the first few years after the introduction of Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) in 1973, Gary Gygax, who had the strongest impact on the fantasy elements of the game, denied any direct influences from fantasy author J.R.R. Tolkien. Many players recognized immediately that numerous D&D character and creature names came directly from the books. But it took until 1977 for intellectual property lawyers from a firm which had licensed the rights to Tolkien’s work to send a cease-and-desist order, at which point TSR Inc. (then known as Tactical Studies Rules) Gygax’s publishing house, famously changed the names of characters with ties to those works. Thus, in basic D&D “hobbit” became “halfling,” and “ent” became “treant.” At The Strong, we have multiple editions of the first D&D sets with Tolkien-inspired names and those that followed with synonymic names. And we have versions of another game that may have incited the change.

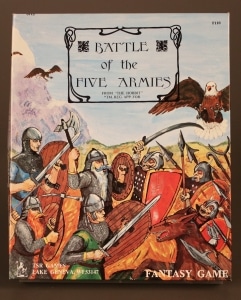

The first D&D edition, called the “basic set” by enthusiasts, was published in 1973. In 1975 the wargamer Larry Smith designed a war game titled The Battle of Five Armies, based on a battle taken directly from Tolkien’s The Hobbit. Published by a small California firm, Smith’s game caught the attention of the folks at TSR and they reviewed it and other competing war games in the premier issue of their newly published fan magazine, Dragon, in 1976. Later that year, TSR purchased the rights to publish Smith’s game. According to scholars, it was this game, with a front-and-center title stolen unabashedly from The Hobbit, which alerted and alarmed the law firm about a year later. Meanwhile TSR enjoyed its first wave of success and became a corporation. But it quietly transformed many of its character and creature names in the basic D&D set, and soon The Battle of Five Armies game disappeared from store shelves and order forms. In the year 2000, Gary Gygax, perhaps hoping to set the record straight, stated that the Tolkien works had a “strong impact” on the development of Dungeons & Dragons. And some years later, The Strong had reason to write to the Tolkien estate with a request.

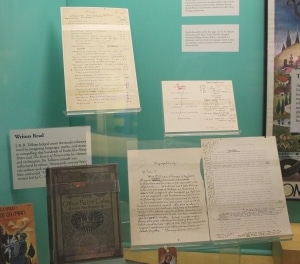

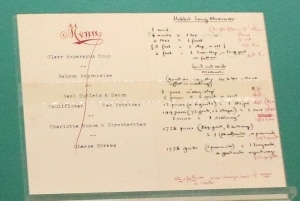

Within The Strong National Museum of Play, many guests enjoy Reading Adventureland, The Strong’s children’s literature exhibition. When the team planned this exhibit, we determined to feature one author’s works in-depth within each of the five literature type sections. In the fantasy section, we chose Tolkien. The team planned to feature reproductions of each writer’s first attempts at beginning a classic work—a sample of each writer’s first page if possible. (We also found that E.B. White began Charlotte’s Web at least six different times.) I wrote to the literary executors of the Tolkien estate, then overseen by his son Christopher. I soon heard back from a solicitor. Yes, we could get reproductions of Tolkien’s attempts and notes—one of them famously outlined on a menu. Yes, we must pay dearly for them. And yes, after printing one copy, we must destroy the disk they sent us. We made the reproduction documents and, 15 years later, they are still on display at The Strong. You won’t see them anywhere else. You don’t even need to brave any dungeons, dragons, or intellectual property attorneys.

Within The Strong National Museum of Play, many guests enjoy Reading Adventureland, The Strong’s children’s literature exhibition. When the team planned this exhibit, we determined to feature one author’s works in-depth within each of the five literature type sections. In the fantasy section, we chose Tolkien. The team planned to feature reproductions of each writer’s first attempts at beginning a classic work—a sample of each writer’s first page if possible. (We also found that E.B. White began Charlotte’s Web at least six different times.) I wrote to the literary executors of the Tolkien estate, then overseen by his son Christopher. I soon heard back from a solicitor. Yes, we could get reproductions of Tolkien’s attempts and notes—one of them famously outlined on a menu. Yes, we must pay dearly for them. And yes, after printing one copy, we must destroy the disk they sent us. We made the reproduction documents and, 15 years later, they are still on display at The Strong. You won’t see them anywhere else. You don’t even need to brave any dungeons, dragons, or intellectual property attorneys.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.