Spending most of my time at home with my young children has revealed that I’m not especially innovative when it comes to crafts. Thankfully, there are people willing to experiment with materials to develop activity kits and craft ideas for kids. Their work has resulted in some notable successes, as well as a few questionable developments over the years.

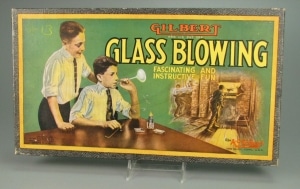

In 1909, Alfred Carlton Gilbert founded the A. C. Gilbert Company. The company, guided by Gilbert, created toys related to science, technology, and invention. Some of the activity sets proved dangerous. In the 1920s, the Gilbert Glass-Blowing Kit introduced boys (Gilbert’s primary demographic at that time) to the art of using a blowtorch to create test tubes and beakers from scratch. (I can see modern parents recoiling everywhere because, after all, what could go wrong with kids, open flames, and molten glass!) Under the direction of Gilbert, Carleton J. Lynde, PhD prepared Experimental Glass Blowing for Boys, in which he instructed boys to hold a glass tube in the “flame of the alcohol lamp.” Making laboratory glass malleable enough to shape requires temperatures of several hundred degrees—hot enough to cause third-degree burns. The company later produced the Gilbert Kaster Kit for making lead soldiers and the Atomic Energy Lab, complete with radioactive material.

In 1909, Alfred Carlton Gilbert founded the A. C. Gilbert Company. The company, guided by Gilbert, created toys related to science, technology, and invention. Some of the activity sets proved dangerous. In the 1920s, the Gilbert Glass-Blowing Kit introduced boys (Gilbert’s primary demographic at that time) to the art of using a blowtorch to create test tubes and beakers from scratch. (I can see modern parents recoiling everywhere because, after all, what could go wrong with kids, open flames, and molten glass!) Under the direction of Gilbert, Carleton J. Lynde, PhD prepared Experimental Glass Blowing for Boys, in which he instructed boys to hold a glass tube in the “flame of the alcohol lamp.” Making laboratory glass malleable enough to shape requires temperatures of several hundred degrees—hot enough to cause third-degree burns. The company later produced the Gilbert Kaster Kit for making lead soldiers and the Atomic Energy Lab, complete with radioactive material.

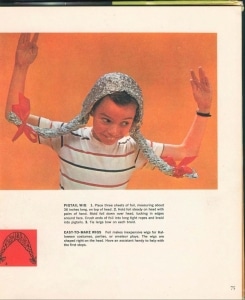

Following World War II, many corporations attempted to adapt their war-time innovations for the peacetime marketplace. Aluminum had loomed large in defense manufacturing and companies like Reynolds and Alcoa now needed to determine a way to market aluminum foil to housewives. Promoting aluminum foil as a kitchen staple proved relatively easy, but household sales couldn’t match the profits from wartime demands. Companies began to advertise aluminum foil as a crafting supply. The introduction to Alcoa’s Book of Decorations touts “All these easy-to-make decorations were designed by Conny of Alcoa…. Conny travels the country showing children and grown-ups how to make gay, lovely things of foil.” Crafts include a “glittering pleasure train,” “a big foil snow man,” “inexpensive wigs,” and “a soulful mermaid,” among others. The authors gloated that foil is “inexpensive, flame-proof, easily obtained, and simple enough to be handled by amateur decorators.” Aside from my fond memories of aluminum foil swans used for takeaway at upscale restaurants in the 1980s, I’d prefer not to participate in a foil craft session.

Following World War II, many corporations attempted to adapt their war-time innovations for the peacetime marketplace. Aluminum had loomed large in defense manufacturing and companies like Reynolds and Alcoa now needed to determine a way to market aluminum foil to housewives. Promoting aluminum foil as a kitchen staple proved relatively easy, but household sales couldn’t match the profits from wartime demands. Companies began to advertise aluminum foil as a crafting supply. The introduction to Alcoa’s Book of Decorations touts “All these easy-to-make decorations were designed by Conny of Alcoa…. Conny travels the country showing children and grown-ups how to make gay, lovely things of foil.” Crafts include a “glittering pleasure train,” “a big foil snow man,” “inexpensive wigs,” and “a soulful mermaid,” among others. The authors gloated that foil is “inexpensive, flame-proof, easily obtained, and simple enough to be handled by amateur decorators.” Aside from my fond memories of aluminum foil swans used for takeaway at upscale restaurants in the 1980s, I’d prefer not to participate in a foil craft session.

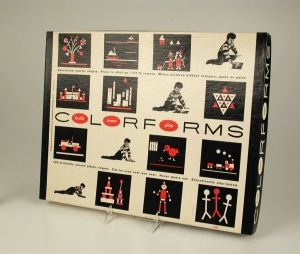

The 1950s also involved experimentations with new plastics. Harry Kislevitz had just gotten out of the U.S. Navy in 1951, and his wife, Patricia, had completed an art degree. The pair loved to make art, but they found the materials too pricey. Harry called around and found someone who had a plastic material that had been used to make pocketbooks. The Kislevitzs purchased primary colors of the material and began to cut out shapes. They discovered that the absence of air between the material and a smooth surface created a vacuum that held the piece in place on mirrors, windows, and the refrigerator. Harry quickly realized that they had a marketable art toy and Colorforms was born. The first Colorforms were spiral-bound booklets filled with geometric shapes that could be placed and repositioned on neutral play boards. F.A.O. Schwarz placed the first order for 1,000 sets and Colorforms emerged as an instant success. In 1957, the Kislevitzes discovered the power of licensing and completed their first deal for a Popeye Colorforms set, soon to be followed by a succession of cartoon, comic book, and other characters. New Colorforms sets are still made today, but it’s the elegance and simplicity of the early sets that encourage unstructured creativity.

The 1950s also involved experimentations with new plastics. Harry Kislevitz had just gotten out of the U.S. Navy in 1951, and his wife, Patricia, had completed an art degree. The pair loved to make art, but they found the materials too pricey. Harry called around and found someone who had a plastic material that had been used to make pocketbooks. The Kislevitzs purchased primary colors of the material and began to cut out shapes. They discovered that the absence of air between the material and a smooth surface created a vacuum that held the piece in place on mirrors, windows, and the refrigerator. Harry quickly realized that they had a marketable art toy and Colorforms was born. The first Colorforms were spiral-bound booklets filled with geometric shapes that could be placed and repositioned on neutral play boards. F.A.O. Schwarz placed the first order for 1,000 sets and Colorforms emerged as an instant success. In 1957, the Kislevitzes discovered the power of licensing and completed their first deal for a Popeye Colorforms set, soon to be followed by a succession of cartoon, comic book, and other characters. New Colorforms sets are still made today, but it’s the elegance and simplicity of the early sets that encourage unstructured creativity.

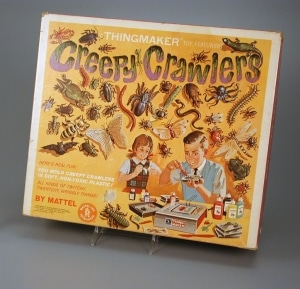

In the early 1960s, Mattel introduced Vac-U-Form, a plastic molding machine that kids could use to create boats, cars, and log cabins. While Vac-U-Form was innovative, Mattel knew that it needed to further expand. In the 1950s and 1960s, themes of mind-control, paranoia, and monsters were rampant, and activity sets began to incorporate America’s preoccupation with science fiction, horror, and edgy humor. Edgar Burns, an engineer at Mattel, purchased plastic bugs from a local magic store, had the Mattel model shop attach them to a plastic base, and then had a vendor metal plate them to form a mold. At the next products meeting, Burns brought his bugs and pitched the idea to management. It was a hit and management gave him a budget to do a preliminary design of the Vac-U-Maker. The initial product was too expensive to produce; management tasked Burns with creating a low-cost, free-standing heater for a set that could produce all sorts of creepy critters. In 1964, Mattel introduced the final product—The Thingmaker: Creepy Crawler Set. The set included a series of die-cast molds resembling various bugs, spiders, worms, and rodents, bottles of “Plastigoop” (liquid plastisol), and an open-face electric hot plate. When the Plastigoop cured, it formed semi-solid, rubbery replicas of centipedes, spiders, cockroaches, and other chill-inducing critters. The Thingmaker sold well and Mattel later introduced Maker-Paks that included Fighting Men, Creeple People, and Fright Factory.

In the early 1960s, Mattel introduced Vac-U-Form, a plastic molding machine that kids could use to create boats, cars, and log cabins. While Vac-U-Form was innovative, Mattel knew that it needed to further expand. In the 1950s and 1960s, themes of mind-control, paranoia, and monsters were rampant, and activity sets began to incorporate America’s preoccupation with science fiction, horror, and edgy humor. Edgar Burns, an engineer at Mattel, purchased plastic bugs from a local magic store, had the Mattel model shop attach them to a plastic base, and then had a vendor metal plate them to form a mold. At the next products meeting, Burns brought his bugs and pitched the idea to management. It was a hit and management gave him a budget to do a preliminary design of the Vac-U-Maker. The initial product was too expensive to produce; management tasked Burns with creating a low-cost, free-standing heater for a set that could produce all sorts of creepy critters. In 1964, Mattel introduced the final product—The Thingmaker: Creepy Crawler Set. The set included a series of die-cast molds resembling various bugs, spiders, worms, and rodents, bottles of “Plastigoop” (liquid plastisol), and an open-face electric hot plate. When the Plastigoop cured, it formed semi-solid, rubbery replicas of centipedes, spiders, cockroaches, and other chill-inducing critters. The Thingmaker sold well and Mattel later introduced Maker-Paks that included Fighting Men, Creeple People, and Fright Factory.

In subsequent years, advances in technology and changes in play patterns have led to a plethora of activity sets ranging from Making Scents Perfume Kit to Tootsweet to Pom-Pom Pets and Poopsie Pooey Puitton Slime Surprise. Today, I am going to simplify my life and teach my three-year-old how to use salt dough to make shapes.