Did you wear a wristwatch when you were a kid? I recall owning at least half a dozen watches, all prized possessions, but I don’t remember checking my wrist very often. When a collections project here at the National Museum of Play at The Strong unearthed a Funtime Barbie watch that sent me into a fit of nostalgia, I started thinking about how kids perceive time—and it rarely has to do with clocks.

Sure, kids have to live by clock time to wake up for school, hustle to practice, and march off to bed, but adults usually serve as the timekeepers. Actual time might matter to kids who know when their favorite television show starts, though in this age of on-demand programming, that’s becoming less of a concern. Children are more likely to be aware of time in ways that are relevant to them: how quickly the fading daylight will force them to end their game of hide and seek, or how agonizingly slowly the bedroom brightens on Christmas morning. Twenty-five minutes of recess passes more rapidly than 25 minutes of math, assuming you prefer freeze tag to fractions. Dinnertime is when the meal appears on the table, no matter what the clock says. And while Tamagotchi, Webkinz, or FarmVille players might not consult their watches to keep their critters fed and fields plowed, they frame their days around these perpetual and time-sensitive demands.

Sure, kids have to live by clock time to wake up for school, hustle to practice, and march off to bed, but adults usually serve as the timekeepers. Actual time might matter to kids who know when their favorite television show starts, though in this age of on-demand programming, that’s becoming less of a concern. Children are more likely to be aware of time in ways that are relevant to them: how quickly the fading daylight will force them to end their game of hide and seek, or how agonizingly slowly the bedroom brightens on Christmas morning. Twenty-five minutes of recess passes more rapidly than 25 minutes of math, assuming you prefer freeze tag to fractions. Dinnertime is when the meal appears on the table, no matter what the clock says. And while Tamagotchi, Webkinz, or FarmVille players might not consult their watches to keep their critters fed and fields plowed, they frame their days around these perpetual and time-sensitive demands.

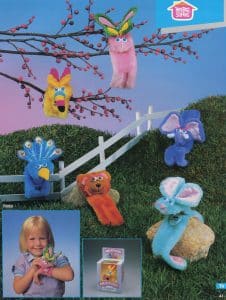

I may not have been keeping time by the watch that came with my Barbie doll, but I loved sharing fashions with her. My favorite timepiece was my Hasbro Watchimal, a furry animal hiding a digital watch in its mouth. When I wore the plush peacock on my wrist, I thought I was harboring the most thrilling secret. My Swatch watch made me feel mature beyond my seven years—a far cry from my Watchimal phase—though in retrospect, it was barely business casual. I regarded my Mickey Mouse watch, a souvenir from my grandparents’ vacation in Orlando, as a talisman reminiscent of that faraway fantasy land. None of these accessories helped me keep appointments or avoid burning a pie, but I was a kid then. The way I viewed the world and perceived time went hand in hand—and had little to do with my wrist.

I may not have been keeping time by the watch that came with my Barbie doll, but I loved sharing fashions with her. My favorite timepiece was my Hasbro Watchimal, a furry animal hiding a digital watch in its mouth. When I wore the plush peacock on my wrist, I thought I was harboring the most thrilling secret. My Swatch watch made me feel mature beyond my seven years—a far cry from my Watchimal phase—though in retrospect, it was barely business casual. I regarded my Mickey Mouse watch, a souvenir from my grandparents’ vacation in Orlando, as a talisman reminiscent of that faraway fantasy land. None of these accessories helped me keep appointments or avoid burning a pie, but I was a kid then. The way I viewed the world and perceived time went hand in hand—and had little to do with my wrist.