Here’s a story about global toy distribution that’s driven by natural forces rather than consumer trends.

There are few things I like better than heading to the beach to get lost in a good book. I read every day for my job at the museum, but my beach reading is play. Mark Twain was right when he said that “work consists of whatever a body is obliged to do. Play consists of whatever a body is not obliged to do.” If it’s a spy novel or a mystery story, I want it complicated and convoluted. If it’s a history book, I make sure that it’s exotic and arcane, remote in time and place. If it’s a scientific tome, I want the inside story of a barely familiar topic. I want something new. I want to be transported.

There are few things I like better than heading to the beach to get lost in a good book. I read every day for my job at the museum, but my beach reading is play. Mark Twain was right when he said that “work consists of whatever a body is obliged to do. Play consists of whatever a body is not obliged to do.” If it’s a spy novel or a mystery story, I want it complicated and convoluted. If it’s a history book, I make sure that it’s exotic and arcane, remote in time and place. If it’s a scientific tome, I want the inside story of a barely familiar topic. I want something new. I want to be transported.

However, a beach chair will only let you sit and read so long, and then it’s time for a walk. I make a habit of picking up trash that’s washed up—the monofilament that will entangle a pelican if it floats back out to sea, the plastic sheet that will choke a turtle, the six-pack rings that ensnare the snouts of seals and dolphins. I find toothpaste tubes from Venezuela and suntan lotion containers with text in French from Saint Lucia or Saint Tropez, who knows! Along the way I always meet some serious beachcomber who’s good for a short chat or a longer conversation.

Last time, I met a woman who toted an impressive haul of bottle caps, crankcase oil containers, an ice cube tray, a swimsuit top (!?), sunglasses, a weathered flip flop, fishing netting, and a rubber ducky—the classic bathtub toy. I sang her Ernie’s song, “Rubber Ducky, joy of joys/when I squeeze you, you make noise/Rubber Ducky I’m awfully fond of you!” We chatted about the gyres that swirl in the oceans and the Texas-sized floating trash patches that rotate at their centers. Her hobby was launching messages in bottles and waiting for a reply. One of her bottles made its way from Florida’s Atlantic Coast up the Gulf Stream, up the North Atlantic Drift past Ireland and Britain, through the Bay of Biscay where it rounded Spain and, incredibly, snaked through the Strait of Gibraltar. An Italian girl from Genoa sent back the envelope she found inside, reminding the receiver that Christopher Columbus had navigated the same currents that transported the bottle.

Last time, I met a woman who toted an impressive haul of bottle caps, crankcase oil containers, an ice cube tray, a swimsuit top (!?), sunglasses, a weathered flip flop, fishing netting, and a rubber ducky—the classic bathtub toy. I sang her Ernie’s song, “Rubber Ducky, joy of joys/when I squeeze you, you make noise/Rubber Ducky I’m awfully fond of you!” We chatted about the gyres that swirl in the oceans and the Texas-sized floating trash patches that rotate at their centers. Her hobby was launching messages in bottles and waiting for a reply. One of her bottles made its way from Florida’s Atlantic Coast up the Gulf Stream, up the North Atlantic Drift past Ireland and Britain, through the Bay of Biscay where it rounded Spain and, incredibly, snaked through the Strait of Gibraltar. An Italian girl from Genoa sent back the envelope she found inside, reminding the receiver that Christopher Columbus had navigated the same currents that transported the bottle.

When I met the beachcomber again a couple days later, she carried something besides the bag of marine debris, a book that she pressed into my hands: Flotsametrics and the Floating World: How One Man’s Obsession with Runaway Sneakers and Rubber Ducks Revolutionized Ocean Science by Curtis Ebbesmeyer and Eric Scigliano. Here was a barely familiar topic worth diving into.

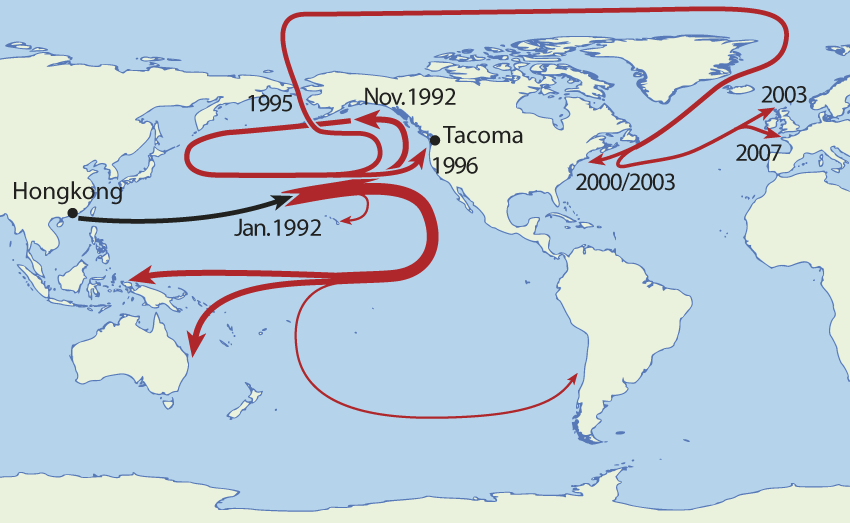

In the book I found the story of a 1992 storm that washed three containers off the deck of a freighter outbound from Hong Kong. These contained 28,800 almost indestructible Chinese bathtub toys designed to survive dozens of dunkings. Starting at the site of the accident on the International Date Line about halfway to the North Pole, the bulk of the duckies immediately headed West and South to Indonesia and Australia. But a second group, a tub toy flotilla 10,000 strong, began a counterclockwise journey East. (Follow their course on the map below.) By 1993 the toys, now borne west by the Subarctic Current, were washing up in the Aleutian Islands, three hundred miles west of the International Date Line. A flock of plastic ducks landed at Sitka, Alaska; a percentage floated on toward Japan. A few duckies made a sharp right turn and peeled off at the Bering Strait where they were taken up by arctic ice, and, orbiting at the fringe at the rate of about a mile a day, were transported toward the North Atlantic. In 2000 some of the duckies were sighted off the coast of Maine. By 2007 duckies were heading toward Scotland and Brittany. Sixteen years after the spill, some of the ducks had floated 34,000 miles, a distance nearly one and a half times the radius of the earth. Some may make it into the Mediterranean; others may curl back toward Florida.

Someday I hope to look up from a book, a history of piracy perhaps, and find washed up at my feet one of the duckies—bleached, cracked, and gnawed by sea creatures—that floated on the same currents that once bore Spanish galleons up the “gold coast” of Florida. I won’t be able to pretend that the discovery will have had nothing to do with work—I work at The Strong, after all—and I’ll donate the ducky to The Strong’s National Museum of Play collections. Things—like the plot of a great book—have a way of circling back.