Biologists who study the fossil record note that dramatic blooms in the number and diversity of species interrupt long periods of stasis or gradual change in animal forms. Paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould termed this phenomenon “punctuated equilibrium” and wrote a book, Wonderful Life, about the sudden efflorescence of fossils during the Cambrian period about 550 million years ago. Interestingly, despite the drastic difference in timescales, this phenomenon has a parallel in the history of games, for at certain times the number and diversity of games has expanded particularly dramatically.

Researchers to the expansive storage areas of The Strong witness this firsthand when they open the cabinets and view our unparalleled collection of board games. Whereas in the first half of the 19th century there are only scattered examples of board games such as Mansion of Happiness and Checkered Game of Life, after the Civil War hundreds of richly-colored board games like the Game of the Messenger Boy, Authors, and Yacht Race hit the market. There are a variety of reasons for this sudden explosion in the quantity of board games. Some of it had to do with the continued rise of the middle class, which afforded people money to spend on leisure goods. Improved manufacturing and technological processes such as the invention of chromolithographic printing also helped spur the production and sale of games. But a key reason was, I believe, what historians have identified as a transportation revolution that occurred during this period.

The railroad transformed almost every aspect of life in the 19th century. It shattered distance, tied together far-flung markets, and moved goods at a fraction of what it had once cost to ship freight. In the world of play, cheap train transport let game manufacturers safely and inexpensively transport boxed copies of games. As a result, manufacturers like Parker Brothers, McLoughlin Brothers, and Milton Bradley churned out an ever-increasing number of board games that they sent by rail to cities all over the United States. By 1890, the number of games had easily increased 50 fold from what it had been a half century earlier.

During the 20th century, manufacturers distributed games roughly along the same lines that were established in the 19th century. True, they used ships, trucks, and planes in addition to trains, but they still shipped a mass-manufactured, boxed product that consumers bought at physical retail locations. This model held true even when video games emerged in the 1970s, as manufacturers shipped boxes of games to consumers who bought them in stores. While the number of video games in the last quarter of the century proved large, it represented geometric, not exponential growth from the older board game industry.

Today we’re in the midst of a second transportation revolution, one that is similarly transforming the way we play. Unlike the physical tracks of the railroad network, this transportation revolution is digital, running on server farms, fiber optics, and the wireless spectrum. We generally think of it as a distribution or communication revolution, but its effects on the way we deliver goods are as disruptive as the transportation revolution that the railroad introduced. And its effects on game design and distribution are profound.

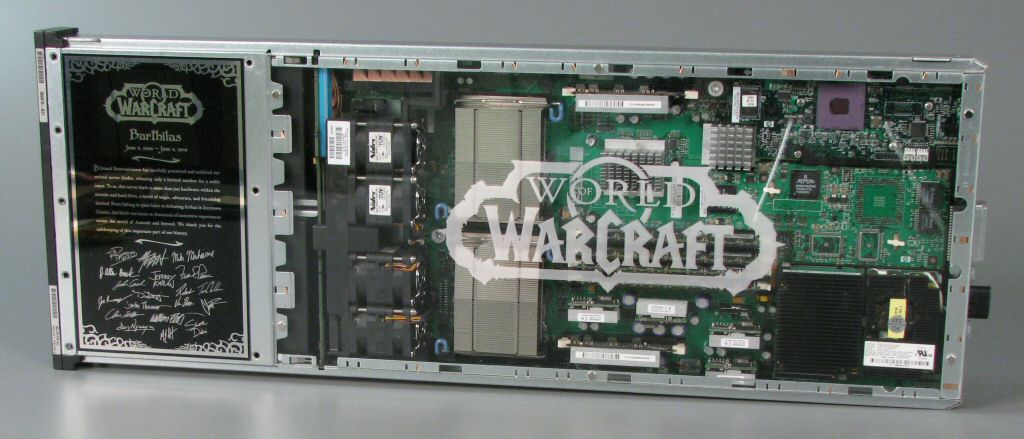

Consumers now download games in numbers exponentially greater than they bought cartridges, disks, and CD-ROMs in the 1970s or 1980s. Channels like Steam for PC, the App Store and Google Play for mobile devices, and Xbox Live and the PlayStation Network for consoles provide users with hundreds of thousands of titles from which to choose. Meanwhile, subscription-based and free-to-play games proliferate at a rapid rate. Not only are games increasing in number, but they’re becoming more various, with nimble Indie titles like Flappy Bird and Device 6 sharing space with massively multiplayer games like League of Legends or World of Warcraft.

Consumers now download games in numbers exponentially greater than they bought cartridges, disks, and CD-ROMs in the 1970s or 1980s. Channels like Steam for PC, the App Store and Google Play for mobile devices, and Xbox Live and the PlayStation Network for consoles provide users with hundreds of thousands of titles from which to choose. Meanwhile, subscription-based and free-to-play games proliferate at a rapid rate. Not only are games increasing in number, but they’re becoming more various, with nimble Indie titles like Flappy Bird and Device 6 sharing space with massively multiplayer games like League of Legends or World of Warcraft.

This shift from physical to digital distribution bodes well for game players, but it also has tremendous long-term implications for how museums and other institutions preserve these games. How do we store these games? What do we do if they run on clients or servers that companies no longer support? What impact do Digital Rights Management policies have on the long-term viability of these software titles? These are all crucial problems we’re exploring here at The Strong’s International Center for the History of Electronic Games, because there’s no doubt that the revolution has begun, and we want to make sure that we preserve a representative record of games created using this new distribution method for future generations to come.

By Jon-Paul Dyson, Director, International Center for the History of Electronic Games and Vice President for Exhibits

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.