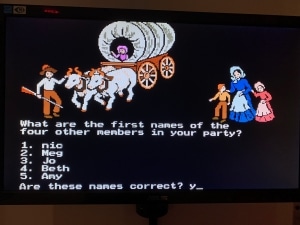

I recently revisited World Video Game Hall of Fame inductee The Oregon Trail, traveling west with extra oxen, plenty of bullets, and cash to spare. My colleague Laurie was laid up with typhoid, and Jo died of cholera near Independence Rock. I succumbed to the same malady before South Pass, alas! I think I started too late in summer because finding water became an issue, but I still had plenty of bullets. Despite criticism aimed at its biases, especially for insensitive portrayals of indigenous people, The Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium’s (MECC) longest running and best-selling educational video game is still fun. When I play as one of the travelers I’m focused. I want to beat the odds and make it to Oregon. And I’m learning as I play.

I recently revisited World Video Game Hall of Fame inductee The Oregon Trail, traveling west with extra oxen, plenty of bullets, and cash to spare. My colleague Laurie was laid up with typhoid, and Jo died of cholera near Independence Rock. I succumbed to the same malady before South Pass, alas! I think I started too late in summer because finding water became an issue, but I still had plenty of bullets. Despite criticism aimed at its biases, especially for insensitive portrayals of indigenous people, The Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium’s (MECC) longest running and best-selling educational video game is still fun. When I play as one of the travelers I’m focused. I want to beat the odds and make it to Oregon. And I’m learning as I play.

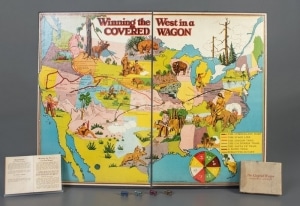

The Oregon Trail video game virtually immerses school-aged kids into an idealized mid-19th century American Westward Expansion, which you can learn more about in The Strong’s new online exhibit. But The Oregon Trail isn’t the first time an educational firm devised a game to help the lesson stick. Many of the earliest game boards were maps, meant to teach geography. Founded in 1920, Scholastic Publishing Company (now Scholastic Corporation, the world’s largest publisher and distributor of children’s books and print and digital educational materials) published the Winning the West in a Covered Wagon board game in 1927. The game simulated westward travel during the mid-19th-century California Gold Rush, but it did not stop at geography. The similarities to The Oregon Trail video game are remarkable.

In Winning the West in a Covered Wagon, the game’s players each control (surprise!) a metal covered wagon playing piece, starting in Washington, DC. Once outbound, there are several trails to choose, including the famous one to Oregon. The spinner shows forward moves (good roads, reinforcements), but spinning a negative move (storms, hostile Indians) redirects the opposing player’s wagon backwards—sometimes onto a dead-end trail. When resting on a fort or a city, a wagon is safe. Hazards and bonuses built into the board also guide the wagons forward or back. Yes, there are far fewer options and obstacles than in the video game version of The Oregon Trail, and certainly less feeling of immersion in this analog journey. But it’s a little bit evocative to physically slide the tiny wagons along the path and wait for the next safe fort or dangerous buffalo stampede, while deviously moving your opponent’s wagon backwards. And in this game, nobody dies.

In Winning the West in a Covered Wagon, the game’s players each control (surprise!) a metal covered wagon playing piece, starting in Washington, DC. Once outbound, there are several trails to choose, including the famous one to Oregon. The spinner shows forward moves (good roads, reinforcements), but spinning a negative move (storms, hostile Indians) redirects the opposing player’s wagon backwards—sometimes onto a dead-end trail. When resting on a fort or a city, a wagon is safe. Hazards and bonuses built into the board also guide the wagons forward or back. Yes, there are far fewer options and obstacles than in the video game version of The Oregon Trail, and certainly less feeling of immersion in this analog journey. But it’s a little bit evocative to physically slide the tiny wagons along the path and wait for the next safe fort or dangerous buffalo stampede, while deviously moving your opponent’s wagon backwards. And in this game, nobody dies.

I’d like to believe that young players 90 years ago imagined their own raucous group of traveling companions and halted their play to discuss the severity of the rainstorms, the joy of finding food, or the worry of a snakebite. As for me, Meg and Amy are waiting in Oregon. Wagons ho!

I’d like to believe that young players 90 years ago imagined their own raucous group of traveling companions and halted their play to discuss the severity of the rainstorms, the joy of finding food, or the worry of a snakebite. As for me, Meg and Amy are waiting in Oregon. Wagons ho!

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.