Video game historians hoping to trace the intellectual and cultural influences of some games may find themselves crossing oceans to do so. Beginning in the mid-1980s, Japanese video games spread to North America and across the globe, exporting Japanese culture and energizing the slumping home console industry. ICHEG’s recent acquisition of a collection of nearly 7,000 Japanese video games helps preserve and document that history. As part of The Strong’s comprehensive collection of tens of thousands of other electronic, board, and pen-and-paper games, these newly acquired games aid the study of the museum’s earlier games that inspired Japanese designers to new creative heights, such as Sir-Tech’s Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord (1981).

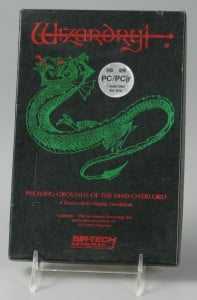

Video game historians hoping to trace the intellectual and cultural influences of some games may find themselves crossing oceans to do so. Beginning in the mid-1980s, Japanese video games spread to North America and across the globe, exporting Japanese culture and energizing the slumping home console industry. ICHEG’s recent acquisition of a collection of nearly 7,000 Japanese video games helps preserve and document that history. As part of The Strong’s comprehensive collection of tens of thousands of other electronic, board, and pen-and-paper games, these newly acquired games aid the study of the museum’s earlier games that inspired Japanese designers to new creative heights, such as Sir-Tech’s Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord (1981).

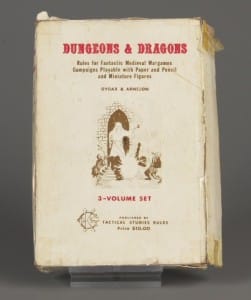

Created by Andrew Greenberg and Robert Woodhead, Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord drew its inspiration from the seminal pen and paper RPG, Dungeons & Dragons. Much like Dungeons & Dragons, Wizardry gave players the opportunity to create a character by choosing a “race” (dwarves, elves, gnomes, hobbits, and humans), “alignment” (good, neutral, and evil), and “class” (fighter, mage, priest, thief). Players could also add to their character’s power or advance their level through gameplay. Combining these elements with text, simple color graphics, and a first-person dungeon crawl-style that sent players searching through labyrinths brimming with treacherous creatures and hidden treasures, Wizardry brought Dungeons & Dragons to life. As Computer Gaming World declared in May 1982, Wizardry was “one of the all time classic computer games. It set the standard by which all fantasy role playing games should be compared.”

When writer and game designer Yuji Horii discovered Wizardry at the 1983 Apple Fest in San Francisco, the new title ignited his imagination and immediately influenced his future games. He first incorporated elements from Wizardry into the Nintendo Famicom version of Enix’s adventure game The Serial Murders at Port Pier (1985). As Koichi Nakamura reprogrammed the game, Horii added monster encounters and borrowed the Wizardry phrase “Monster surprised you!” Horii wanted to make a true Wizardry-like RPG for the Famicom, but he also worried that the millions of Japanese home console owners would find RPGs too complicated.

When writer and game designer Yuji Horii discovered Wizardry at the 1983 Apple Fest in San Francisco, the new title ignited his imagination and immediately influenced his future games. He first incorporated elements from Wizardry into the Nintendo Famicom version of Enix’s adventure game The Serial Murders at Port Pier (1985). As Koichi Nakamura reprogrammed the game, Horii added monster encounters and borrowed the Wizardry phrase “Monster surprised you!” Horii wanted to make a true Wizardry-like RPG for the Famicom, but he also worried that the millions of Japanese home console owners would find RPGs too complicated.

Horii therefore made his Dragon Quest (1986) as straightforward an RPG as he could. Instead of giving players several character choices, Horii focused the game on developing one character in-depth from a fighter to a knight. The one character needs to recover a sacred artifact stolen by the evil Dragonlord. Along the way, the player’s character gains strength and experience by fighting back monsters and rescuing a princess. The combination of Dragon Quest’s gameplay, manga artist Akira Toriyama’s illustrations, composer Koichi Sugiyama’s original score, and Horii’s Shohen Jump magazine articles introducing Japanese players to RPGs, helped sell more than 2 million copies of the game and created a Japanese cultural phenomenon.

Though initially inspired by the North American RPG, Dragon Quest helped establish a distinctly Japanese console-based RPG genre that would evolve in the game’s sequels and in other Japanese RPGs such as the Final Fantasy series. Today, the Dragon Quest series remains as popular as ever for many Japanese gamers.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.