Invented in the 1950s to simulate surfing on land, the skateboard enjoyed a second wave of popularity 20 years later as a West Coast drought obliged residents to drain their backyard swimming pools. The drought resulted in a wealth of vacant, dry, sloping, and gently-curved concrete surfaces that tempted skateboarders to sneak in and show their stuff.

Since then, tinkerers, materials scientists, and engineers have improved skateboards’ laminated decks, fashioned the truck assemblies in lightweight aluminum, and attached softer neoprene wheels that permit higher speeds, greater maneuverability, and the gravity-defying acrobats’ ollies, nollies, kickflips, bluntslides, and grabgrinds that neighborhood kids now seem to master with routine ease.

In recent years, skateboarders have approached near-perfection in the mash-up of surfing and roller-skating. And for those who made it their business to sell skateboards, this new kind of play hit the target-marketers bull’s-eye at the intersection of the novel and the familiar.

But with the impulse to play guiding technological evolution, perfection never stays perfect for long. And so we now hear of the “post-modern” skateboard, a new toy that makes a conceptual leap beyond.

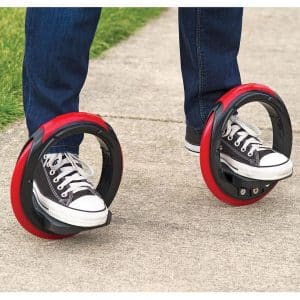

The post-modern skateboard is so hip and minimal, in fact, that designers have done away with both the “skates” and the “board,” and replaced them with two separated 10-inch rubber wheels, each with an attached foot platform. The axels are gone, and so are the nose guards and tail devils that leave a trail of sparks. With no decks to paint on, the distinctive graphics—skulls, pin-up girls, cartoon aliens, and Manga monsters—have vanished as well. All that’s left after the non-essential elements have been pared away are the wheels and the ride itself.

The post-modern skateboard is so hip and minimal, in fact, that designers have done away with both the “skates” and the “board,” and replaced them with two separated 10-inch rubber wheels, each with an attached foot platform. The axels are gone, and so are the nose guards and tail devils that leave a trail of sparks. With no decks to paint on, the distinctive graphics—skulls, pin-up girls, cartoon aliens, and Manga monsters—have vanished as well. All that’s left after the non-essential elements have been pared away are the wheels and the ride itself.

Riders of these “annular,” “side-winding circular skates” ride sideways as they would on a snowboard. They propel themselves by weight-shifting and leg-swiveling, alternating leaning motions back and forward. The unconnected wheels enable riders to turn sharply and spin freely. Neither grass patches nor short stretches of dirt present obstacles. This concept of a skateboard sets skateboarders free.

But will the skateboard that’s not a skateboard catch on? Is it too free of the past to be a hit? Is post-modern too modern? This is hard to say. Run-flat tires, monkfish, fuel cells, and e-readers failed at first. Newness itself can militate against any product; consumers are often biased toward the status quo. Will the post-modern skateboard go the way of Pepsi “Blue,” Touch of Yoghurt Shampoo, Country Toaster-Eggs, or Barbie’s friend “Pregnant Midge”?

Players are always wondering “what’s next?” Anticipation is always built into play. And only time will tell if side-winding circular skates are maneuverable enough in the marketplace to find that sweet spot where novelty meets familiarity.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.