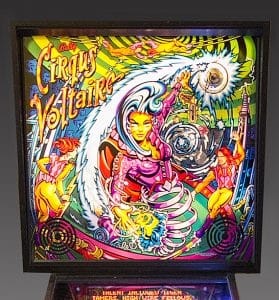

Before I came to The Strong, my exposure to pinball had been limited to the Barbie Shakin’ Pinball handheld video game that I received for Christmas 1995. I have definitely come a long way in my pinball knowledge since then, from learning the proper terms for components I never knew existed (pop bumpers are my favorite) to discovering the game’s tumultuous and sometimes scandalous past (mob connections, anyone?). Once I saw the machines up close, I became fascinated with the several different types of artwork that appear on every pinball machine. The cabinet artwork can be painted, stenciled, and in more modern times, applied as decals or screen-printed directly onto the sides and front of the machine. It often features eye-catching motifs and bright colors. Once the side art grabs your eye and draws you closer, you notice the detail and intricate game design of the playfield. But my favorite part of a pinball machine is the backglass. This area often features the most complex artwork, displaying characters, multiple scenes, or other images that tell the story of the game. What interests me most about pinball backglasses, however, is not the imagery itself. I am fascinated by how the technique used to decorate the backglass connects to other forms of artwork throughout history, including some examples in the collection here at The Strong.

Traditionally, a pinball backglass is created by screen-printing an image face-down to the back of a piece of glass so that the scene can be viewed from the front. The colored image is then typically followed with additional layers of white or black in order to control the diffusion of light. These layers—especially the black—are sometimes applied selectively to increase contrast in dynamic areas, such as where lights flash behind numbers as points are scored during game play. The idea of painting an image on the back of a transparent support was in use long before pinball’s invention. Artists have been creating reverse glass paintings by applying images backward onto glass or other transparent materials for centuries. This technique created a popular form of artwork and sometimes served as a replacement for stained glass in religious icons. Reverse glass painting was also commonly used to decorate clock faces and other furniture elements. Later, animation artists at Walt Disney and other film studios painted characters and other moving features on the back of transparent film, which could be switched back and forth over pre-drawn background images to create the illusion of movement.

The idea of painting an image on the back of a transparent support was in use long before pinball’s invention. Artists have been creating reverse glass paintings by applying images backward onto glass or other transparent materials for centuries. This technique created a popular form of artwork and sometimes served as a replacement for stained glass in religious icons. Reverse glass painting was also commonly used to decorate clock faces and other furniture elements. Later, animation artists at Walt Disney and other film studios painted characters and other moving features on the back of transparent film, which could be switched back and forth over pre-drawn background images to create the illusion of movement.

The purpose of applying an image to the back of a transparent material varies with the function of the object in question, but these examples share some common characteristics. The transparent support allows light to pass through the artwork, and the artist can choose to manipulate this feature as an artistic or functional element. Clockmakers used reverse glass painting to add decoration to the protective cover while retaining visibility of the important information on the clock face. Animators utilized transparency as a way to quickly change a character into different poses on the same background. Similarly, pinball backglasses serve as both decoration and as a creative and engaging way to display changing information such as scored points or how many balls are left to play.

Besides just being an interesting art historical tidbit, the connections between backglasses and other forms of artwork are beneficial to those of us who have accepted the charge to care for, and preserve, these objects. This is especially true for conservators. Because pinball machines are still not quite considered “traditional” museum objects, few conservators have had the chance to work with them directly. More than a few of us, however, have been fascinated and frustrated by the condition issues that commonly occur with reverse glass paintings or animation cels. Because these same condition issues often appear in backglasses, the conservation solutions that have been successful in preserving similar forms of artwork give us a place to start.

Besides just being an interesting art historical tidbit, the connections between backglasses and other forms of artwork are beneficial to those of us who have accepted the charge to care for, and preserve, these objects. This is especially true for conservators. Because pinball machines are still not quite considered “traditional” museum objects, few conservators have had the chance to work with them directly. More than a few of us, however, have been fascinated and frustrated by the condition issues that commonly occur with reverse glass paintings or animation cels. Because these same condition issues often appear in backglasses, the conservation solutions that have been successful in preserving similar forms of artwork give us a place to start.

If you want to learn more about pop bumpers, mob connections, backglass artwork, and more, visit The Strong’s exhibit, Pinball Playfields, now open on the museum’s first floor.