Before I came to The Strong, I taught writing and literature courses at the Rochester Institute of Technology and elsewhere, which fits right in with writing electronic games blogs. As video games occupy more and more of our playtime, it is not surprising that some educators are finding opportunities to use gaming to teach writing and critical reading skills. Here are three examples I find particularly interesting:

1. BiblioBouts

1. BiblioBouts

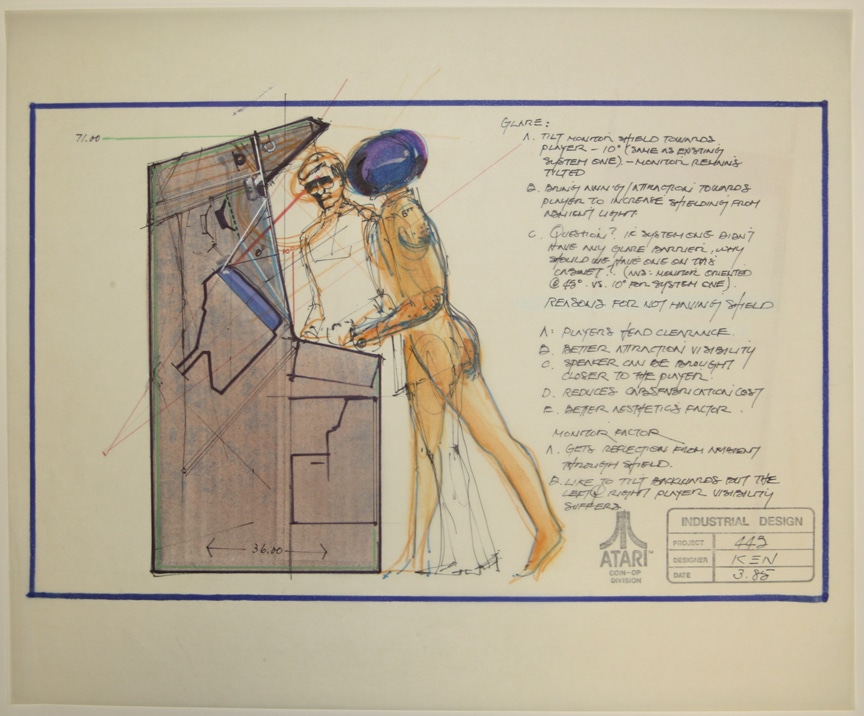

With funding from the Institute of Museum and Library Studies, researchers at the School of Information of the University of Michigan and the Center for History and New Media at George Mason University created BiblioBouts, an online social game that taught undergraduate students information literacy skills. Classmates competed against one another in a series of bouts that introduced skills required for research in the library. You remember—those buildings that served as a central place for scholarship from the 3rd century to about 2005. The game challenged students to evaluate each other’s selections of resources based on content, credibility, and relevance. Imagine for a moment that you’re writing a paper on electronic gaming and the professor suggests you visit the library’s archives to locate primary sources such as an Atari arcade concept drawing for Computer Space or Will Wright’s notes for SimCity 2000.

2. Telling a Story through Video Games

Last year, Professor Trent Hergenrader of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee presented “Build Me a World: Building and Emergent/Environmental Storytelling in the Creative Writing Classroom” at the Association of Writers and Writing Programs conference. Hergenrader explained environmental storytelling as a “story through the experience of traveling through real, or imagined space” that is “unlike a linear movie, the audience will have choices along their journey.” He demonstrated how he applied the idea and concepts presented in role-playing games to teach principles of fiction writing. During class, 25 students individually created 10 items, 5 locations, and 5 characters, and then collaborated through a group Wiki space, modeled after Fallout 3’s Wiki, to build an enormous and detailed world. I found myself preoccupied with the “Chocolate Chopper” and a witty student disclaimer: “while it may be incredibly delicious, don’t count on it giving you a lift out of the hot zone.” Hergenrader found that the collaborative writing exercises gave students the skills to negotiate reality, the opportunity to focus on intricate details, and an engaging format to discuss techniques.

3. Oh No

Earlier this year, programmer Cameron Kunzelman ventured to make a game that required a player to type out lengthy sentences to defeat enemies, rather than engage in direct combat (his idea reminded me of 1999 arcade game The Typing of the Dead). The task proved daunting. He decided to instead “make something fast and fun” and ended up producing Oh No, a game that requires a player to “always stay one step ahead of the terrifying wraith head of Michel Foucault.” I recall begrudgingly reading Foucault’s theories of surveillance in an English course that examined globalization and literature. Foucault elaborated on the social theory of panopticon design (a round building with an observation tower in the center) as a means to create discipline and order. Kunzelman’s decision to use a monstrous Foucault head that chases after a tiny figure alludes to the French philosopher’s social theories. Oh No game play seems lackluster, but if a student pays attention in class, she’ll realize that knowledge of history, literature, and philosophy generates humor and creativity in a variety of formats.

These applications of games and modern educational techniques demonstrate that technology can sometimes enrich the quality of research and the learning experience of students studying the humanities.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.