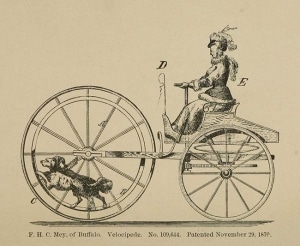

As a cycling enthusiast, I was a thrill to see a velocipede—an early form of bicycle—in the conservation lab. Pierre Lallement and Pierre Michaux patented the design for the velocipede in 1866 before Lallement moved to New Haven, Connecticut, and made improvements to the velocipede on his own. He also gave license to American bike-builders for variations of the velocipede. These early wheelmen obsessed over different ways to power a bicycle—steam, electricity, or dog-powered locomotion.

As a cycling enthusiast, I was a thrill to see a velocipede—an early form of bicycle—in the conservation lab. Pierre Lallement and Pierre Michaux patented the design for the velocipede in 1866 before Lallement moved to New Haven, Connecticut, and made improvements to the velocipede on his own. He also gave license to American bike-builders for variations of the velocipede. These early wheelmen obsessed over different ways to power a bicycle—steam, electricity, or dog-powered locomotion.

Most velocipedes haven’t survived. They were melted down as scrap metal during war efforts. When I examined this 1870 example, I marveled at how heavy and unwieldy it was. It would have been very difficult to balance when in motion. Even standing still on its mount, the velocipede was inclined to topple over. Preventing the velocipede from being unstable in its display mount was the primary goal of conservation treatment. A new mount would support the axles, but the weight of the frame needed to be balanced and stable.

In contrast to feather-light alloy bicycle frames today, the velocipede in The Strong’s collection has a bevel-edge backbone made of heavy forged iron, with bold pinstriping on its front fork. A bracket attaches the metal seat to the curved backbone and the arched wrought iron handlebars terminate in a square taper at each end, lacking grips would have been made of turned wood. Typical of velocipedes, the wheels have wood hubs and staggered spokes, which were painted at one time, before the paint flaked and the wood aged and split. The metal tires are bolted and screwed to the wood rims.

When I first looked at the velocipede in the conservation lab, it showed signs of having been ridden through mud and dirt. The rider had shaken the joints loose, as one would expect of a “boneshaker” with metal tires and no spring-loaded mechanisms to soften the vibrations of cobblestone, dirt, and grassy paths. The steering column, triangular brace, and front fork flexed in all directions against the backbone. There were no modern bearings or bushings in the steering assemblage, just hard iron against soft brass with a little grease applied. I could imagine what a rough, shaky ride this would have been. Even scarier is that there are no brakes. Slowing would have been accomplished by pedaling backwards against the dir ect-drive cranks on the front wheel axle. Early bicycles sometimes used “spoon” brakes that were rod-actuated to put pressure on the rim or tire to slow down. Another possible way of braking was to lean back in a spring-loaded saddle, causing a brake to engage on the rear wheel.

The velocipede’s steering assemblage needed to be adjusted to prevent stress on the frame and brass steering tube. The steering assemblage was difficult to loosen or tighten without cleaning, so the parts were removed for cleaning. All spacers, tube, and parts were cleaned in a vibratory tumbler with walnut shell pieces followed by a round in an ultrasonic cl eaner. After cleaning, the “166” inscription was more visible. Original parts that were brass were usually highly polished when they were made although the years of grime and grease had turned the brass carbon black.

The velocipede’s steering assemblage needed to be adjusted to prevent stress on the frame and brass steering tube. The steering assemblage was difficult to loosen or tighten without cleaning, so the parts were removed for cleaning. All spacers, tube, and parts were cleaned in a vibratory tumbler with walnut shell pieces followed by a round in an ultrasonic cl eaner. After cleaning, the “166” inscription was more visible. Original parts that were brass were usually highly polished when they were made although the years of grime and grease had turned the brass carbon black.

The velocipede exhibited extensive metal corrosion overall. In the same way that a well-loved cast iron skillet builds a resilient surface, the iron frame had developed an appealing patina that I did not want to disturb. So I lightly cleaned the cast iron, sufficient to remove embedded grime, grease, and corrosion on the axles, pedal spindles, and steering tube while maintaining the patina. This cleaning would help prevent dust from sticking to any residual grease.

The paint pinstriping on the wood wheel rims and the iron forks and frame was revealed after I removed the grime. Bright gold heavy pinstriping was typical of velocipedes and might have been applied by carriage painters of the 19th century. Barely legible inscriptions on the frame indicate the bike’s maker, Larkin of Portland, Maine.

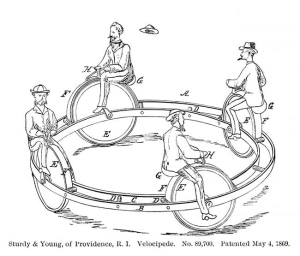

In the late 19th century, cycling invention moved quickly, producing dozens of patents for bicycles, velocipedes, monocoques, tricycles, and other amusements. The designs r ange from practical examples we still recognize today to absurd machines that look like something from a Doctor Seuss book.

I find it interesting to see which bike ideas caught on and which did not. As high-wheeled penny farthings took the place of velocipedes, riders enjoyed being as high as horse-drawn carriages. With such height came increased risk of losing one’s balance. Mark Twain advised “Get a bicycle. You will not regret it, if you live,” after his attempts to learn to ride a penny farthing, in Taming the Bicycle. I am pleased that conservation treatment tamed the velocipede’s bad case of “the Wobbles” as Twain called it. The velocipede is now on exhibit in One History Place, where you can step into the past and experience life like it was more than a century ago.