At a loss for what to write next, John Steinbeck embarked on a tour of the country in 1960, accompanied by his standard poodle, Charley. The trip resulted in an extended meditation about the state of American life called Travels with Charley. Beyond the travelogue and observations that the book offers, Steinbeck shares numerous comments about his canine travel companion. The great novelist thought Charley was smarter than he was, in some respects. And when he looked into Charley’s eyes, Steinbeck thought he saw a mind-reader. Most dog owners will concur in these two opinions-especially developmentally speaking. After all, no human infant will play keep-away with a Frisbee at five months old. Steinbeck also was convinced that dogs “think humans are nuts.” However, based on observing my own Charlie, who is just growing out of puppyhood, I’d say only that dogs just think we are a bit slow to catch on.

At a loss for what to write next, John Steinbeck embarked on a tour of the country in 1960, accompanied by his standard poodle, Charley. The trip resulted in an extended meditation about the state of American life called Travels with Charley. Beyond the travelogue and observations that the book offers, Steinbeck shares numerous comments about his canine travel companion. The great novelist thought Charley was smarter than he was, in some respects. And when he looked into Charley’s eyes, Steinbeck thought he saw a mind-reader. Most dog owners will concur in these two opinions-especially developmentally speaking. After all, no human infant will play keep-away with a Frisbee at five months old. Steinbeck also was convinced that dogs “think humans are nuts.” However, based on observing my own Charlie, who is just growing out of puppyhood, I’d say only that dogs just think we are a bit slow to catch on.

Even if they’re dubious about our mental capacity, dogs have a long history with people. The most needy and companionable wolves took up with us about 15,000 years ago (some say the relationship goes back much farther than that). Ever since, dogs have been charming us and teaching us how to play. This playful relationship has worked out well for dogs as a species, strategically speaking-for every wild wolf in Canada and the United States there are more than a thousand domesticated dogs.

Even if they’re dubious about our mental capacity, dogs have a long history with people. The most needy and companionable wolves took up with us about 15,000 years ago (some say the relationship goes back much farther than that). Ever since, dogs have been charming us and teaching us how to play. This playful relationship has worked out well for dogs as a species, strategically speaking-for every wild wolf in Canada and the United States there are more than a thousand domesticated dogs.

Here’s an example of the way dogs train us to play. Compared to Steinbeck’s dog, the mutt in my household is only half-poodle (and half mini-poodle at that). But true to the other half of his dubious ancestry, the maternal golden retriever, my Charlie will drop at my feet a ragged tennis ball, a time-honored stick, a much-chewed rope-caterpillar, or a tooth-marked returnable bottle. With a bright look, Charlie seems to say, “Hey, lookee, I’ve got a ball, wanna play?” and then “What do you know, here’s a stick! You throw it, I’ll fetch it,” quickly followed by “I’ve got this great idea. Here’s this bottle thing, you could toss it, then I’d go get it and bring it back.” And next: “Can you believe what I’ve got now? This toy I’ve been chewing would also be perfect for running after.” And seconds later: “Let’s try playing a game with this stick!” And so on and on as if each insistent invitation is also a revelation. Ignore the summons and I’m treated to urgent groans and much scampering about, and maybe a tug at a pant leg or a nip at a toe. Let’s face it, when it comes to play, dogs are dogged in their devotion to the game.

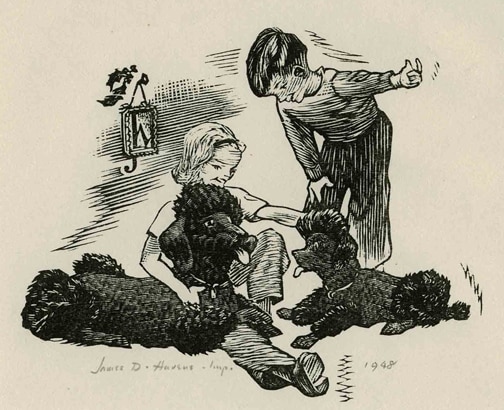

When my Charlie was still just a puppy, he traveled to Cleveland with us for a weekend with friends. There he met Darby, a Wheaten terrier four times his size and ten times his strength. The encounter began the first evening with several hours of domination by Darby. But nearly a full day of counterattack followed. Charlie’s poodle-half knew how to stand on his hind legs and reach Darby’s ears with needle-sharp puppy teeth. Youch! With that, a non-stop, top-speed chase was on, with the terrier fleeing from the goldendoodle across the slippery kitchen tile, up a flight of stairs and down another, peeling out on the wooden floor in the den, over the couch and around the coffee table and up the stairs again.

This was a delightful and somewhat vengeful game for Charlie. But then, in a remarkable turn, Darby discovered something Charlie wanted more than revenge: a buggy-eyed, red rubber beetle that squeaked in a most beguiling way. Darby would stop at the stuffed chair, cast a glance over his shoulder to make sure that Charlie was watching, and then take off, feet churning again in the effort to find some traction, the prize in his mouth, the doodle at his heels, and the humans diving for cover. Darby’s strategy replaced rough and tumble play with a gentler game of keep-away-a doggie version of win-win. The next day we observed that the two had reached an accord, and the fierce little lamblike mutt literally lay down and snuggled up with his new, more respectful, lion-colored friend.

So what can dogs tell us about play and life? John Steinbeck thought his Charley understood French best, as if a francophone heritage was as basic to a poodle’s repertoire as walking on two legs. But all dogs communicate in their own language. They bow when they want to play-it looks like stretching to us, but actually says “Wanna play?” in canine talk. My Charlie and my friend’s Darby were two mismatched pooches who had accelerated, altercated, negotiated, accommodated, and finally affiliated. When conquest failed, the older, wiser, and larger Darby had patiently and ingeniously “self-handicapped” in the interest of prolonging play. Over the course of three days they had become old friends. In the process, they showed us one of the principal dividends that play confers on all players: a heightened social intelligence and the enlarged capacity for friendship. Crafting that kind of bond through play isn’t something we humans do as rapidly or easily as canines. I guess Steinbeck was right; dogs often are smarter than we are.

So what can dogs tell us about play and life? John Steinbeck thought his Charley understood French best, as if a francophone heritage was as basic to a poodle’s repertoire as walking on two legs. But all dogs communicate in their own language. They bow when they want to play-it looks like stretching to us, but actually says “Wanna play?” in canine talk. My Charlie and my friend’s Darby were two mismatched pooches who had accelerated, altercated, negotiated, accommodated, and finally affiliated. When conquest failed, the older, wiser, and larger Darby had patiently and ingeniously “self-handicapped” in the interest of prolonging play. Over the course of three days they had become old friends. In the process, they showed us one of the principal dividends that play confers on all players: a heightened social intelligence and the enlarged capacity for friendship. Crafting that kind of bond through play isn’t something we humans do as rapidly or easily as canines. I guess Steinbeck was right; dogs often are smarter than we are.