Pioneering Chicago-based gaming company Williams Electronics Games, Inc. donated the Williams Pinball Playfield Design Collection, 1946–1995 to The Strong. The collection consists of more than 200 original drawings of playfields (the pinball machines’ surface where the ball rolls) layouts (with a nearly complete set of sketches from 1947 to 1971), hundreds of mechanical drawings of parts assemblies, and numerous examples of pinball concept artwork. Collectively, these one-of-a-kind materials document how Williams created their games and how playfield designs evolved over nearly a half century.

Pioneering Chicago-based gaming company Williams Electronics Games, Inc. donated the Williams Pinball Playfield Design Collection, 1946–1995 to The Strong. The collection consists of more than 200 original drawings of playfields (the pinball machines’ surface where the ball rolls) layouts (with a nearly complete set of sketches from 1947 to 1971), hundreds of mechanical drawings of parts assemblies, and numerous examples of pinball concept artwork. Collectively, these one-of-a-kind materials document how Williams created their games and how playfield designs evolved over nearly a half century.

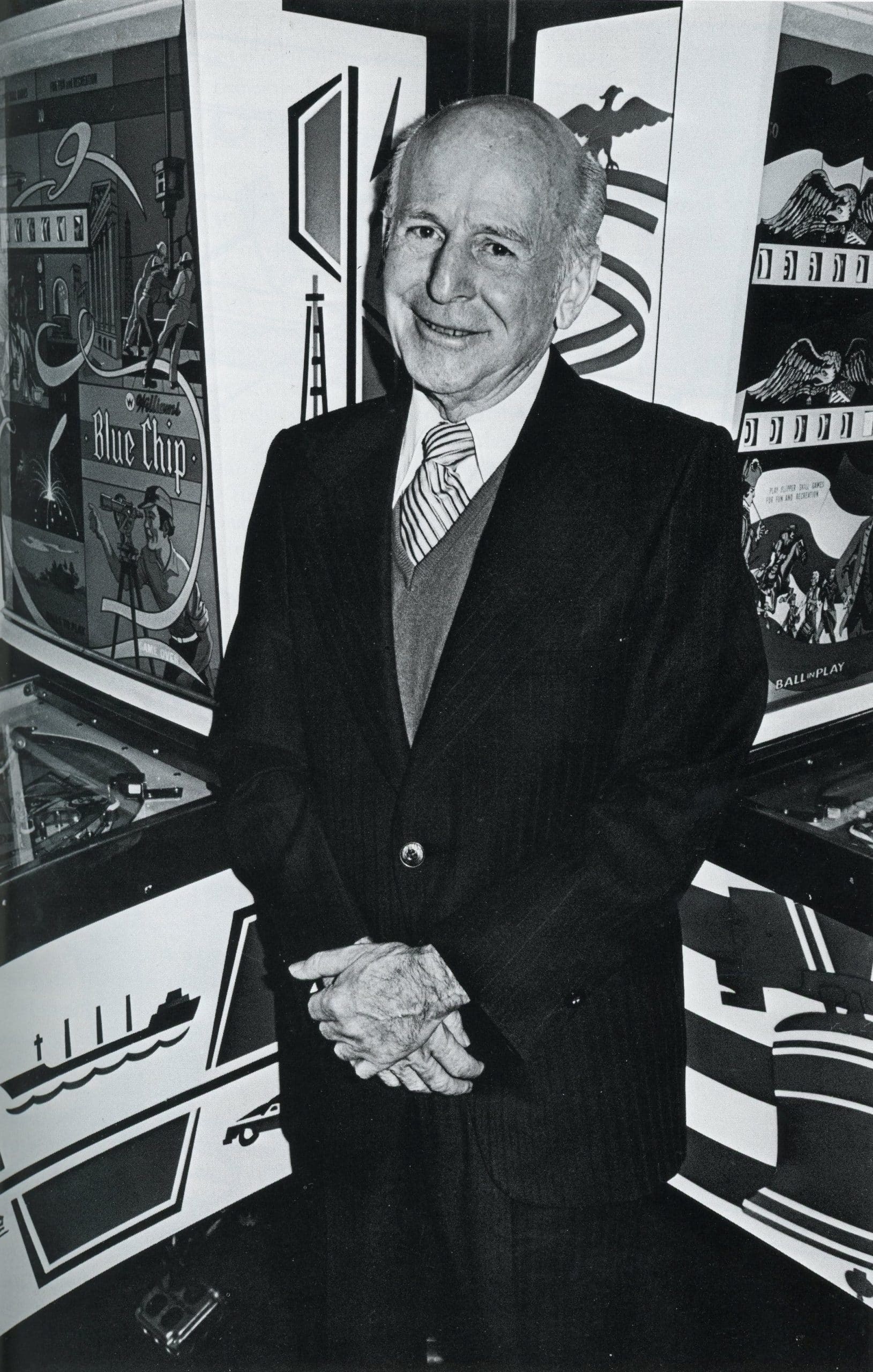

When Harry Williams founded Williams Manufacturing Company in 1943 (later named Williams Electronics Games, Inc.), the Stanford University-trained engineer had already earned a reputation as a master in game design. For example, he invented the first “tilt” mechanism in 1932 to penalize overzealous players for lifting up or nudging games too hard, and in 1933, his game Contact surpassed previous mechanical, bagatelle-style pin games (or early flipperless pinball predecessors) by including, in a single machine, battery power, electric solenoids to “kick” the ball across the playfield, and the sound of an electric doorbell. Contact became an industry sensation, and it helped secure Williams’s position as the “Thomas Edison” of pinball. His stature set the tone for a founder-led company that continued to produce innovative games for decades, even after Williams left the industry.

So how did the company create its pinball machines? This collection provides new insights to the creative processes that produced so many Williams’s pinball machines, including Dynamite (1946), Williams’s second game; Sunny (1947), the company’s first game with flippers; Gusher (1958), the first game with a “disappearing” bumper that dropped into the playfield; and Vagabond (1962), the first game to feature a drop target. Each of these games started in the mind of its designer—Harry Williams initially, and later Gordon Horlick, Sam Stern, Harry Mabs, Steve Kordek, and Norm Clark through the 1970s—who often transferred those ideas to paper through hand-drawn bumpers, kick-out holes, flippers, and other game features that brought playfields to life. The pencil sketches in this collection also show signs of additions and subtractions, as well as erasures and alterations of features, all of which illustrate the complexities of moving a game through the design process. The layouts reveal, as former Williams software developer Duncan Brown told ICHEG, “not only the evolution of the state of the art of pinball design but also changes in the design process itself as draftsmen sometimes did the drawings for the designers or made hand-traced copies that would be marked up for the tooling department to figure out how many holes to drill into the playfield.” Indeed, many of these drawings represent conversations between designers, draftsmen, and the workers who built the playfields themselves. For example, some of Harry Williams’s early playfield layouts included specific notes about a game’s rules and how a specific feature worked because he was living in California at the time and needed to explain his intentions to Gordon Horlick and Sam Stern back in Chicago.

So how did the company create its pinball machines? This collection provides new insights to the creative processes that produced so many Williams’s pinball machines, including Dynamite (1946), Williams’s second game; Sunny (1947), the company’s first game with flippers; Gusher (1958), the first game with a “disappearing” bumper that dropped into the playfield; and Vagabond (1962), the first game to feature a drop target. Each of these games started in the mind of its designer—Harry Williams initially, and later Gordon Horlick, Sam Stern, Harry Mabs, Steve Kordek, and Norm Clark through the 1970s—who often transferred those ideas to paper through hand-drawn bumpers, kick-out holes, flippers, and other game features that brought playfields to life. The pencil sketches in this collection also show signs of additions and subtractions, as well as erasures and alterations of features, all of which illustrate the complexities of moving a game through the design process. The layouts reveal, as former Williams software developer Duncan Brown told ICHEG, “not only the evolution of the state of the art of pinball design but also changes in the design process itself as draftsmen sometimes did the drawings for the designers or made hand-traced copies that would be marked up for the tooling department to figure out how many holes to drill into the playfield.” Indeed, many of these drawings represent conversations between designers, draftsmen, and the workers who built the playfields themselves. For example, some of Harry Williams’s early playfield layouts included specific notes about a game’s rules and how a specific feature worked because he was living in California at the time and needed to explain his intentions to Gordon Horlick and Sam Stern back in Chicago.

By the 1980s, many designers used AutoCAD software to draft their playfield designs, but some designers still used pencil and paper like their predecessors. This collection also includes examples of playfield sketches from Barry Oursler, Python Anghelo, and Mark Ritchie for games such as Joust (1983), Police Force (1990), The Machine: Bride of Pinbot (1991), and Indiana Jones: The Pinball Adventure (1993). For this last game, the documents include a separate design sketch of Ritchie’s “Path of Adventure” player-controlled mini-playfield, which he revised several times during the months of February and March in 1993. In contrast to the earliest drawings, designs like these illustrate how playfields initiated play as ramps, mini-playfields, and toys transformed machines into miniature amusement parks under glass.

By the 1980s, many designers used AutoCAD software to draft their playfield designs, but some designers still used pencil and paper like their predecessors. This collection also includes examples of playfield sketches from Barry Oursler, Python Anghelo, and Mark Ritchie for games such as Joust (1983), Police Force (1990), The Machine: Bride of Pinbot (1991), and Indiana Jones: The Pinball Adventure (1993). For this last game, the documents include a separate design sketch of Ritchie’s “Path of Adventure” player-controlled mini-playfield, which he revised several times during the months of February and March in 1993. In contrast to the earliest drawings, designs like these illustrate how playfields initiated play as ramps, mini-playfields, and toys transformed machines into miniature amusement parks under glass.

Drawings like Ritchie’s “Path of Adventure” remind us of how ephemeral company documentation often is. As Duncan Brown explained, “To my knowledge, no other such body of pinball design history from this era still exi sts. It was only considered useful until a given game was manufactured and sold.” According to Brown, the late designer Steve Kordek likely “rescued and organized these drawings” before Williams closed its pinball division in 1999. The Strong is honored to continue that work and care for the Williams Pinball Playfield Design Collection, which not only helps preserve the history of one of the most significant pinball makers of the 20th century but also complements the museum’s growing collection of Williams pinball machines and pinball design and manufacturing documentation found in the Atari Coin-Op Divisions Collections. Researchers seeking to better understand the thinking and processes behind creating pinball machines after WWII will have an extraordinary collection at The Strong to explore.

sts. It was only considered useful until a given game was manufactured and sold.” According to Brown, the late designer Steve Kordek likely “rescued and organized these drawings” before Williams closed its pinball division in 1999. The Strong is honored to continue that work and care for the Williams Pinball Playfield Design Collection, which not only helps preserve the history of one of the most significant pinball makers of the 20th century but also complements the museum’s growing collection of Williams pinball machines and pinball design and manufacturing documentation found in the Atari Coin-Op Divisions Collections. Researchers seeking to better understand the thinking and processes behind creating pinball machines after WWII will have an extraordinary collection at The Strong to explore.