If you visit The Strong’s America at Play exhibit, among the fascinating and familiar artifacts on display, you will see a 1950s-era cartop boat filled with fishing equipment. An interpretive label next to the wooden watercraft asks guests a provocative question: “Is fishing play?” Ancient fishers almost certainly started out using spears, nets, and hand lines primarily to catch food. However, as early as 2000 BC an Egyptian wall painting illustrates a person gripping a short rod (or pole) with a line and fish attached to it; an image later writers might describe as “angling” or the art or sport of a catching a fish with a rod, line, and hook. Other early Egyptian picture writing and Roman stories suggest that those wealthy enough to have no concern where their next meal came from, fished for sport. Fishing equipment, often called “tackle,” evolved slowly. The lengthening of the rod to make casting (or launching bait) line further distances added a new level of skill and precision. Centuries later, the introduction of reels used to hold, release, and retrieve line by cranking a handle revolutionized fishing into a popular form of play. For me, angling, particularly fishing for largemouth and smallmouth bass, has always been a favorite way to play.

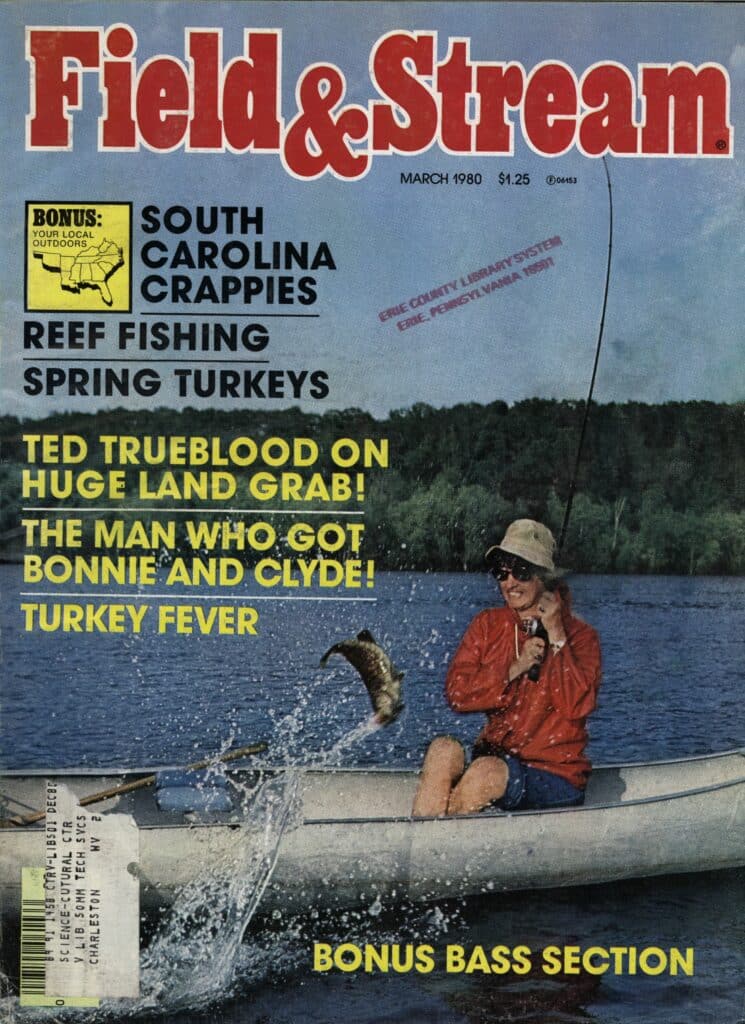

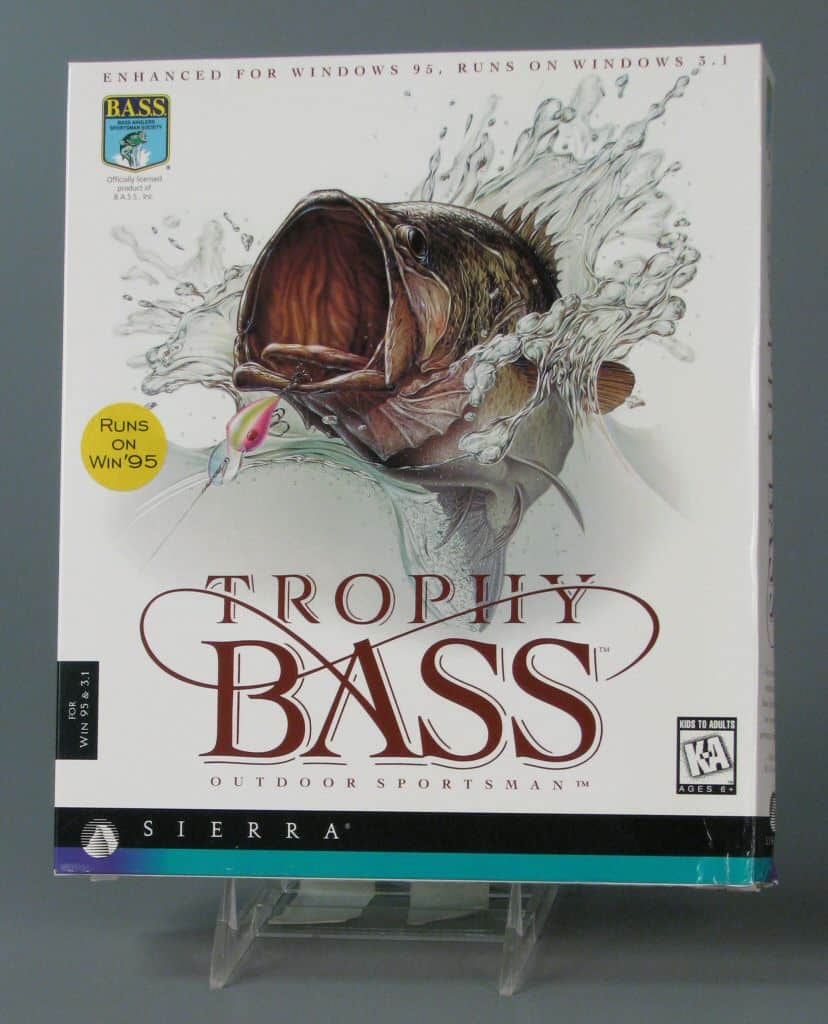

My earliest fishing memories involve watching my father fish for trout in a local pond in central Massachusetts where I grew up. Because my father ate what trout he caught, and I didn’t like to eat fish, five-year-old me didn’t associate fishing with play. I was much more interested in searching the pond’s muddy banks for frogs. Several years later as a teenager, friends introduced me to bass fishing. We spent much of that summer riding our bicycles the five or six miles to go fishing at one of my friend’s lakefront camps. A group of three or four of us fished together as much as we possibly could. I was hooked. Through high school I scoured my public library’s shelves and searched garage sales to find and study books on fishing. I read every word of Field & Stream and Bass Master magazines. I spent some portion of the little money I earned from a variety of jobs on better equipment and new artificial lures that I used to catch more fish. Over the winter as my friends and I waited with anticipation for the ice to melt, we caught digital fish in Sierra’s Trophy Bass: Outdoor Sportsman computer game. I had many experiences with this group of friends, but fishing was perhaps the play that brought us most closely together.

Like many anglers, I enjoyed the comradery of fishing with others. And I still do today when I get the chance to fish with friends and family. But in recent years the kind of fishing I do most often is solitary and more closely resembles what author and champion of nature play Richard Louv has documented and called “deep fishing.” In his book Fly Fishing for Sharks: An American Journey, Louv describes a kind of fishing in which the angler is “more likely to be aware of what [is] going on in the water as well as above it; more cognizant of the plants and animal life on the shore or in the branches above, more immersed in the totality of it.” For me, this kind of deep fishing often starts with finding more remote fishing spots with shallow water and fallen trees that I can only get to in my small, one-person kayak. It requires that I take the time to quietly study my surroundings. The plants, insects, water, weather, and wildlife all offer important information about how best to approach fishing that day. This multisensory and immersive form of play transports me, at least for a few hours, to a natural and entirely different world from my home, office, or virtually anywhere else I visit regularly. As author Jason Gay wrote in a recent Wall Street Journal article, “Fishing is about what’s happening now; you are engaging with the environment and elements, and there’s very little opportunity to sweat what’s happening elsewhere.” Such an experience rewards me even if I don’t catch any fish.

Yet fishing and other forms of nature play taking place in forests or fields and on trails or water provide us with more than just different scenery. They can also help children and adults build their muscles and physical stamina and strengthen their senses and mental health. Such potential benefits and expanded leisure time spurred millions of Americans to start or return to fishing during the COVID-19 pandemic. I suspect, many of these anglers discovered (or rediscovered) that, like me, fishing is one of their favorite ways to play.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.