The Strong’s vast and varied holdings include several hundred artifacts in the museum’s KAR-MI Collection: magician’s props, throwing knives, swords to swallow, theater posters, satiny banners and table covers, and a tattoo set (tattoo set? yes!). But we have few documents or records to explain this interesting mass of materials. So, of course, I have wondered for years: Who was KAR-MI?

The Strong’s vast and varied holdings include several hundred artifacts in the museum’s KAR-MI Collection: magician’s props, throwing knives, swords to swallow, theater posters, satiny banners and table covers, and a tattoo set (tattoo set? yes!). But we have few documents or records to explain this interesting mass of materials. So, of course, I have wondered for years: Who was KAR-MI?

The short answer goes something like this: KAR-MI was the stage name of performer Joseph Hallworth (1872–1956), an itinerant entertainer who worked in Wild West shows, circuses, dime museums, riverboats, vaudeville, movie houses, and other venues from the 1890s to the beginning of World War I.

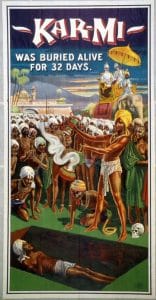

The longer answer is both more complicated and less than perfectly precise. Enthusiasts and historians of magic know KAR-MI from the many vintage posters, theater cards, and ephemera that frequently appear on the antiques market. The posters present KAR-MI as the prince of India and high priest of conjurers and spirit workers. They advertise a number of KAR-MI’s sword-swallowing, knife-throwing, mind-reading, and conjuring feats, proclaiming “Swallows a loaded gun barrel and shoots a cracker from a man’s head,” “KAR-MI was buried alive for 32 days,” and “Swallows a table leg two feet long.” Other posters refer to KAR-MI, his wife, and two sons as the Victorina Show, in which she swallows swords and razors. Ouch! Still others advertise motion picture shows featuring spectacular train wrecks and automobile accidents of cars “traveling at 1,000 mph!” Aside from the posters and Hallworth’s reminiscences that appeared in the 1950s, not much is known about KAR-MI.

The longer answer is both more complicated and less than perfectly precise. Enthusiasts and historians of magic know KAR-MI from the many vintage posters, theater cards, and ephemera that frequently appear on the antiques market. The posters present KAR-MI as the prince of India and high priest of conjurers and spirit workers. They advertise a number of KAR-MI’s sword-swallowing, knife-throwing, mind-reading, and conjuring feats, proclaiming “Swallows a loaded gun barrel and shoots a cracker from a man’s head,” “KAR-MI was buried alive for 32 days,” and “Swallows a table leg two feet long.” Other posters refer to KAR-MI, his wife, and two sons as the Victorina Show, in which she swallows swords and razors. Ouch! Still others advertise motion picture shows featuring spectacular train wrecks and automobile accidents of cars “traveling at 1,000 mph!” Aside from the posters and Hallworth’s reminiscences that appeared in the 1950s, not much is known about KAR-MI.

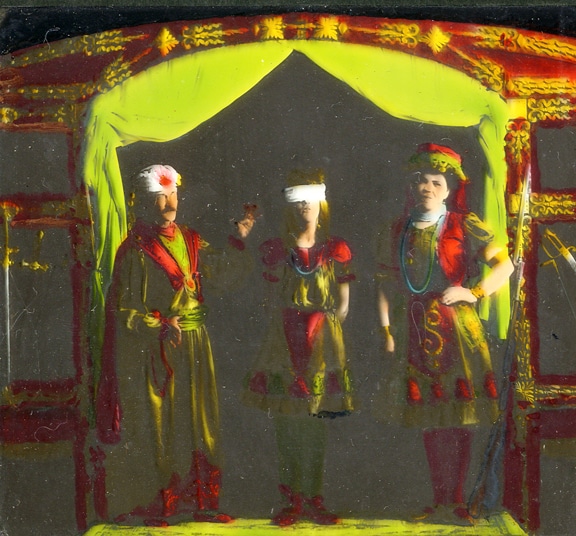

The story that Joseph Hallworth told about himself and his showbiz family always began with his learning to read at the age of three. At six years old, he read the classics and had an “intimate knowledge of Shakespeare, Fielding, Byron, Swift, Balzac, and many others.” (Remember, he was an entertainer, and nothing entertains so well as a good story.) At 14, he ran away from home and, for a few years, worked out West as a fur trapper, prospector, and cowboy. In Kansas, he began his show business career in a “one-ring wagon circus” and went on to perform as a sharp-shootin’, knife-throwin’ cowboy in a medicine show, a Wild West show, and the Chatham Square Museum in New York. When he married, Hallworth and his wife performed together in traveling shows, adding song-and-dance routines, snake charming, fire eating, and fortune telling, along with acts of magic, illusion, and mind-reading. Their sons joined the family business too—one dressed as a female assistant to aid KAR-MI’s illusions, the other as the young Hindu beauty that KAR-MI appeared to make float in midair. Hallworth ended his stage career when his two sons were drafted to serve in World War I. The family retired to a small town in Massachusetts, and Hallworth took up printing and engraving.

The story that Joseph Hallworth told about himself and his showbiz family always began with his learning to read at the age of three. At six years old, he read the classics and had an “intimate knowledge of Shakespeare, Fielding, Byron, Swift, Balzac, and many others.” (Remember, he was an entertainer, and nothing entertains so well as a good story.) At 14, he ran away from home and, for a few years, worked out West as a fur trapper, prospector, and cowboy. In Kansas, he began his show business career in a “one-ring wagon circus” and went on to perform as a sharp-shootin’, knife-throwin’ cowboy in a medicine show, a Wild West show, and the Chatham Square Museum in New York. When he married, Hallworth and his wife performed together in traveling shows, adding song-and-dance routines, snake charming, fire eating, and fortune telling, along with acts of magic, illusion, and mind-reading. Their sons joined the family business too—one dressed as a female assistant to aid KAR-MI’s illusions, the other as the young Hindu beauty that KAR-MI appeared to make float in midair. Hallworth ended his stage career when his two sons were drafted to serve in World War I. The family retired to a small town in Massachusetts, and Hallworth took up printing and engraving.

All the information about KAR-MI—including his own account—is fascinating because it gives context to the materials we have in the National Museum of Play’s collection and some understanding of public entertainment in the early 20th century. On the other hand, the KAR-MI story may be as much an illusion as KAR-MI’s act itself.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.