NPCs are having a moment. That raises, of course, an existential question: can an NPC have a moment?

For those not familiar with the term, NPC stands for Non-Player Character. It refers to some living, sentient being in a game that players interact with in a way that’s not purely hostile. A monster you encounter and fight in a game, with little or no conversation outside the moment of combat, could perhaps be considered an NPC, but in practice monsters seem to fall into a different category. On the other hand, a computer-generated tavern keeper in a fantasy game might be an NPC, as might a space pilot who you hire in a tabletop sci-fi role-playing game.

Unlike characters that are controlled by other players, NPCs are enacted and acted by some sort of dungeon or game master in tabletop games and by software in computer games. Especially in the latter case, this has often meant that the non-player characters exhibit routinized or predictable behavior. In a tavern set in a fantasy roleplaying game, for example, the character might mechanically wash crockery and offer formulaic sayings to the player that are repeated with each interaction. Some comments might be useful: “I’d watch out for the bandits in Templar Woods” could be a helpful piece of advice. Other times the conversation might be banal. “Nice weather we’ve been having lately!”

The inherent silliness of the dialogue and actions of many computer NPCs has prompted people to play act NPCs in real life. I first became aware of the trend a few years ago when my kids pointed me to videos of people pretending to be NPCs in grocery stores, approaching strangers and uttering random sentences such as, “I see three cloaked men going by here recently. Who knows what they could be up to?” In a game, this speech could be an invitation to a side quest, but seeing it applied to some bewildered shopper in real life highlights the unreal absurdity of it. More recently, TikTok stars such as Pinkydoll have made playing NPCs (or uttering nonsensical phrases like “ice cream so good” that sound like NPC dialogue) a serious moneymaker, as well as a social phenomenon. It’s a curious case of life imitating games imitating life.

But where do NPCs come from? Think about it. In traditional games like chess, Monopoly, or parcheesi, there is no such thing as an NPC as we might think of it today. Players might be characters, but the elements of the game do not interact in any independent way apart from the commands of the player or the mechanics of the game. The history of NPCs truly begins with a revolution in game playing, the creation of role-playing games in the 1970s.

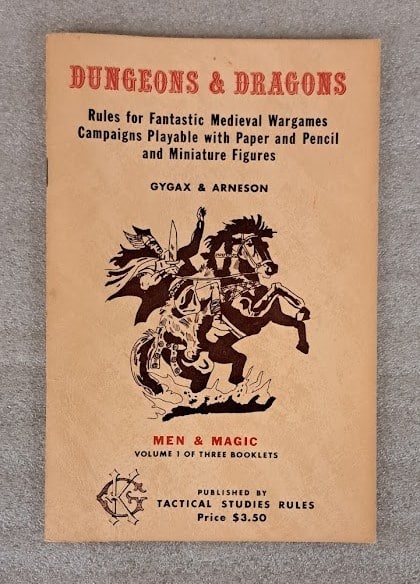

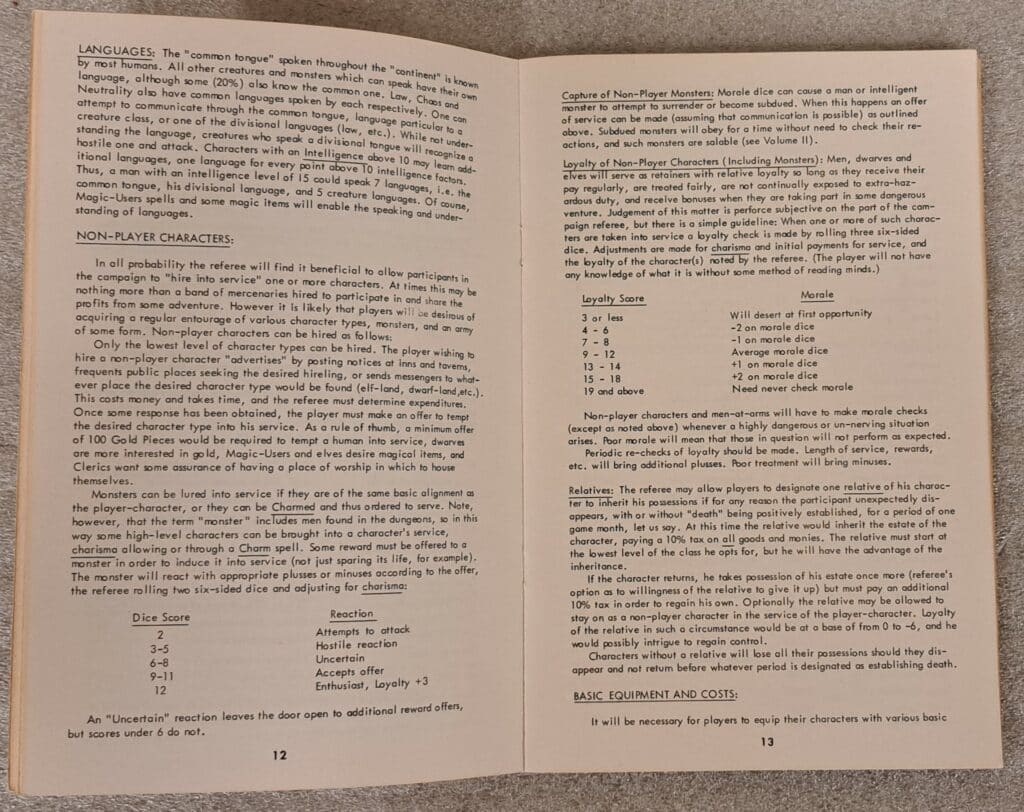

Key to this evolution was Dungeons & Dragons. The first edition of D&D came out in 1974, so I decided to go back and look at one of the copies we have in our collection at The Strong. In this case, I pulled one donated by Bill Hoyt, who had gamed with D&D creators Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson. That first edition (Hoyt used a woodgrain version that looked a little different from the usual “white box” set), consisted of three small booklets. In volume 1, Gygax and Arneson laid out a category of participants in the campaign that they called “Non-player characters,” though in this initial version the NPC’s role usually consisted of being fellow adventurers who were hired for the express purpose of joining the player’s party. Their ongoing loyalty was measured via secret dice rolls by the game’s referee (later known as the “dungeon master”).

Volume 3 (“The Underworld & Wilderness Adventures”) of this original version of Dungeons & Dragons expanded the scope of NPCs, especially as players ventured through wilderness territories. As players passed castles, they would be challenged to joust. If they had their own towns, they could hire specialists, ranging from alchemists to animal trainers. Most importantly, the game began to develop opportunities for non-players to shape the game, not through combat, but as conduits of quests and information. In the section on “RUMORS, INFORMATION, AND LEGENDS,” Gygax and Arneson wrote:

Obtaining such news is usually merely a matter of making the rounds of the local taverns and inns, buying a round of drinks (10-60 Gold Pieces), slipping the barman a few coins (1-10 Gold Pieces) and learning what is going on. Misinformation is up to the referee. Legends will be devised by the referee as the need arises, but they are generally insinuated in order to lead players into some form of activity or warn them of a coming event.

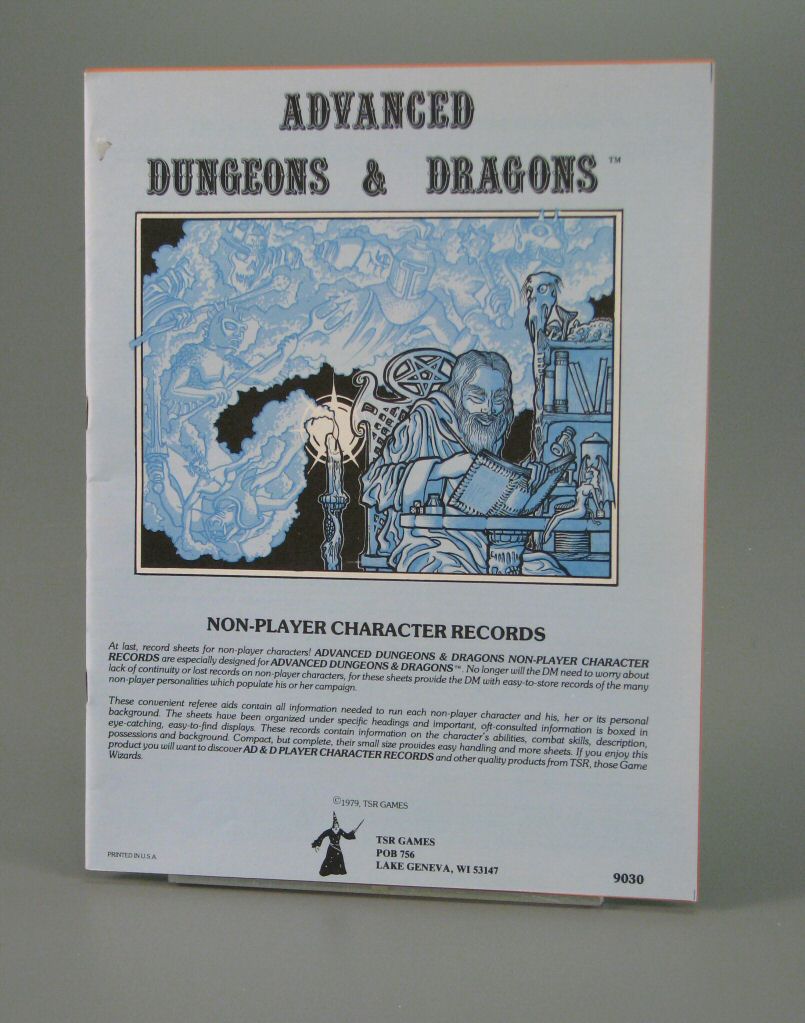

NPCs remained a vital part of Dungeons & Dragons as the game evolved, especially with the introduction of the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons game system in the late 1970s. Gary Gygax, author of the Dungeon Master’s Guide, spent many pages talking about NPCs, their role in the game, how their characteristics and personalities could be generated, and how the dungeon master should bring them to life to move the story along in a way that felt genuine and real, by “assuming the station and vocation of the NPC and creating characteristics—formally or informally according to the importance of the non-player character.” World makers could create their own NPCs, or the Dungeon Master’s Guide offered up tables that allowed the quick generation of NPCs with the roll of a few dice.

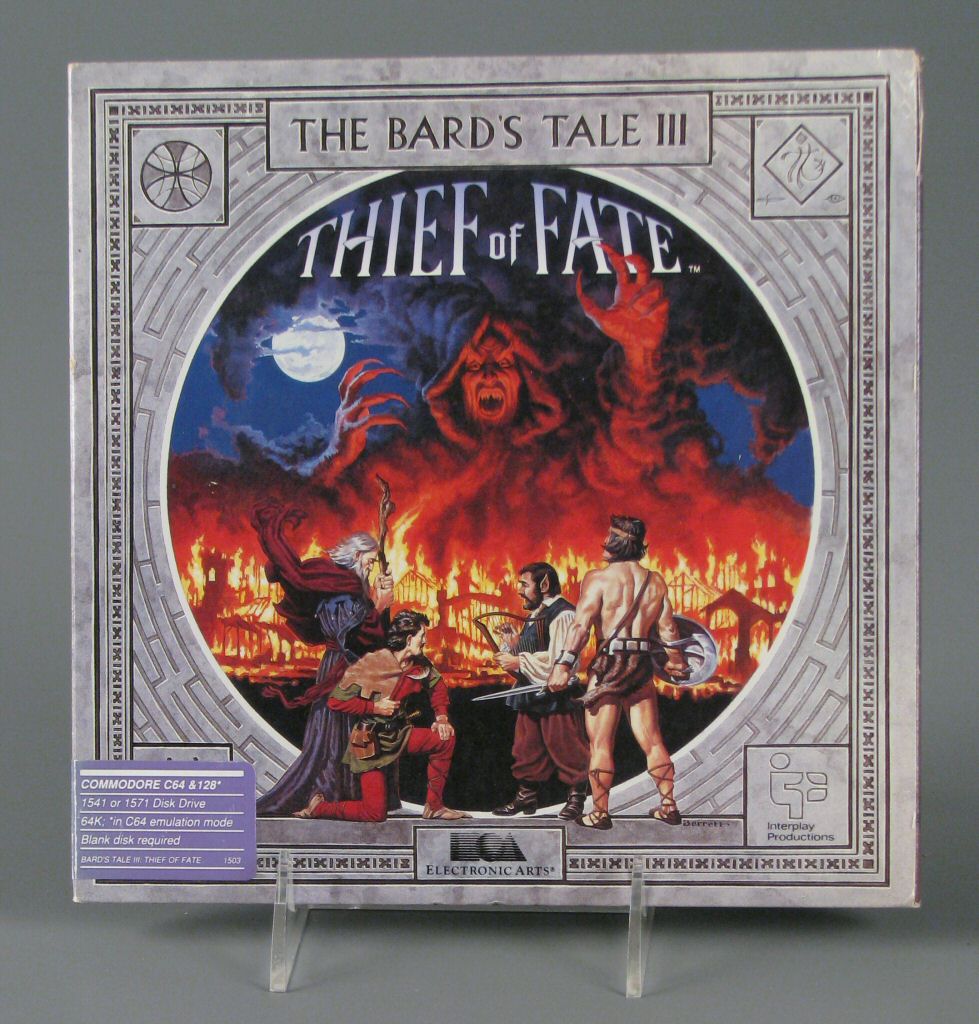

With the migration of role-playing games from tabletops to computers, the use of NPCs became more vital than ever, even as programmers and game designers struggled to breathe genuine life into them. Sometimes players would engage with characters who were placed in the game merely to do one thing, like set players off on a quest, the role of Lord British in Richard Garriott’s first published game Akalabeth (1979) or in the point-and-click adventure King’s Quest (1980). Gradually, games began to introduce more fully realized (though still limited) characters, such as in the successful titles Ultima (1981), Bard’s Tale (1985), and Ultima IV (1985).

In role-playing games, NPCs have generally served four key roles: instrumental, oppositional, allied, or atmospheric. Their most important role is usually the instrumental one, in which the NPC plays some necessary role in moving the story or game along, often by imparting information. Sometimes, however, NPCs are placed in the story to frustrate or slow the player character’s progress. In this way they act like monsters the player might encounter. On the other hand, they sometimes will aid the player, perhaps by offering healing or even joining a party of adventurers to help fight. And sometimes, they are simply there for atmosphere. This is especially prevalent in the large open-world games popular today, where harried game designers need filler material to populate the massive mythical realms they’ve created, and so they sprinkle the world with NPCs.

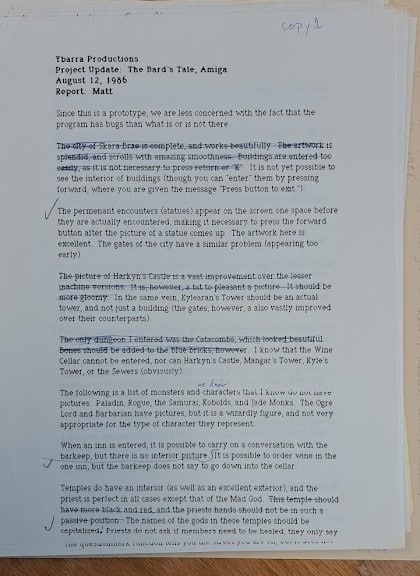

One can see how NPCs have been used in the history of computer game development by looking at the game development notes of Brian Fargo, founder of the pioneering game company Interplay, that are housed at The Strong.

Interplay published many early computer role-playing games, and Fargo took special interest in integrating NPCs as part of his attempts to create well-rounded stories. This shows up even in his early games like The Bard’s Tale (1985), in which one part of the game involves players interacting with an innkeeper at the Scarlet Bard; when players ask for wine, he sends them down into the cellar. One play tester for the Amiga version noticed that the game was buggy and the NPC wasn’t doing his job to keep the game going:

When an inn is entered, it is possible to carry on a conversation with the barkeep, but there is no interior picture. It is possible to order wine in the one inn, but the barkeep does not say to go down into the cellar.

In another game, Bard’s Tale III: Thief of Fate, the initial design document lays out how an NPC will advance the story. In the ruined remains of Skara Brae, the main town of the series, “the players will discover, in the location of the old Review Board, a place with a tired old man in it. He will welcome them and explain they have a mission they alone can perform. He’ll mention, in passing, that the other he has sent has yet to succeed, but he’s confident the adventurers will surpass him. He’ll note that one of the magickers will have to change class to become a (Prophet/Pathfinder/Herald) to facilitate the journeying the characters must do to succeed at their mission. This old man will function as a review board as well, so beginning players will be able to build characters up if they’ve not played a Bard’s game before and have no characters to transfer over.”

The same game (Bard’s Tale 3) also offers examples of oppositional and allied NPCs. One character, Young Hawkslayer, agrees to join the player’s adventuring party and help them if they answer a riddle correctly. Another, Urmech, variously helps or opposes the party. In general, early role-playing games had fewer NPCs who were purely atmospheric, since computer memory was so limited that every encounter had to matter.

As computers became more powerful and memory more available, the use of NPCs became more prevalent and, at times, more sophisticated. Richard Garriott’s Ultima V (1988) featured NPCs that moved to the rhythm of the real world, rising to do business in the morning and closing city gates at night. BioWare’s 1998 roleplaying game Baldur’s Gate used NPCs to make it feel like the player had entered a world that lived and breathed on its own and did not exist solely to serve or impede the interests of the player. As Ray Muzyka, co-founder of BioWare stated in an interview, “We wanted to make [the inhabitants of Baldur’s Gate] feel like real people, not NPCs who were AI-controlled. They really felt like they had personalities and came to life.”

When creating NPCs at massive scale, it will always be a challenge to make them feel real. Back in 1950, in the early days of computing, Alan Turing proposed a test of artificial intelligence which postulated that if a human observer, communicating unseen via typing with a conversational partner, was unable to differentiate whether that partner was a human or a computer, then it would be possible to say, at some level, that computers could think.

We’re not there yet, but with AI and natural language processing improving at a rapid scale, we might, at some point, reach a place where interacting with NPCs feels as real as talking to the people in our everyday life.