My current research project dives into the play histories of Rochester’s former Manhattan St.-Savannah St. neighborhood where The Strong National Museum of Play is now located. Part of what was called the Southeast Loop area, the neighborhood housed residents and businesses since around the Civil War period. It was one of the oldest residential areas in downtown Rochester well into the 1960s and 1970s, until an urban renewal project largely displaced the lower income community in favor of skyrises and apartments that would coax upper middle-class residents back to the city center.

Given this historical background and the myriad shifts of the city, I have been ruminating on how we find and acknowledge historical spaces of play that are not always clearly demarcated like a playground. How do we appreciate and capture the dynamism and energy of a neighborhood that no longer exists so that the stories and voices of the community remain at the center? To help think through these brainstorming questions, I was drawn to replay Chop Suey.

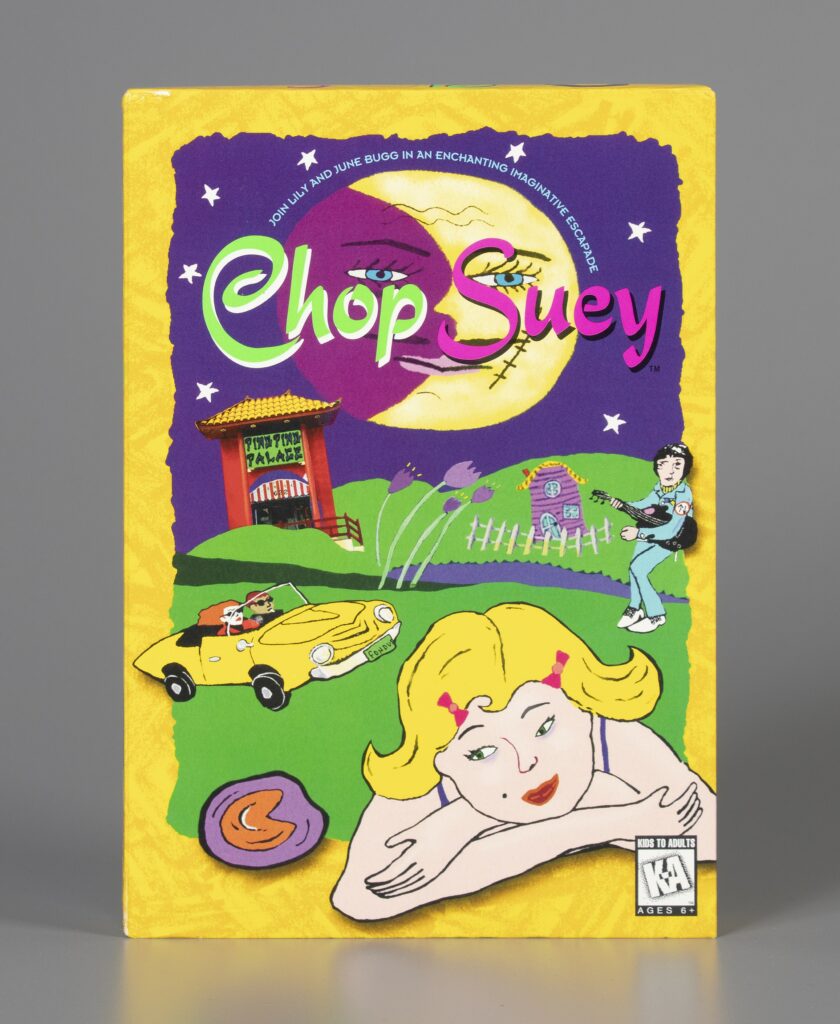

The 1995 interactive PC game by Theresa Duncan and artist Monica Gesue is considered one of the preeminent immersive storytelling games of the 1990s and an important contribution to the “Games for Girls” movement, though neither Duncan nor Gesue intentionally set out to be part of the wave. Although Duncan felt weary of the market research trends attached to the industry’s attention to “girl games,” she created her games with her younger self in mind, wanting computer games to strive for greater creativity and storytelling in order to connect with kids. Chop Suey was intended to “encourage girls’ creativity and enrich their computer skills” while creating an overall sense of wonder and delight through exploration, with Duncan citing author and illustrator Maurice Sendak as a particular influence. As a result, the game is an exemplary experience of how to capture a neighborhood through play.

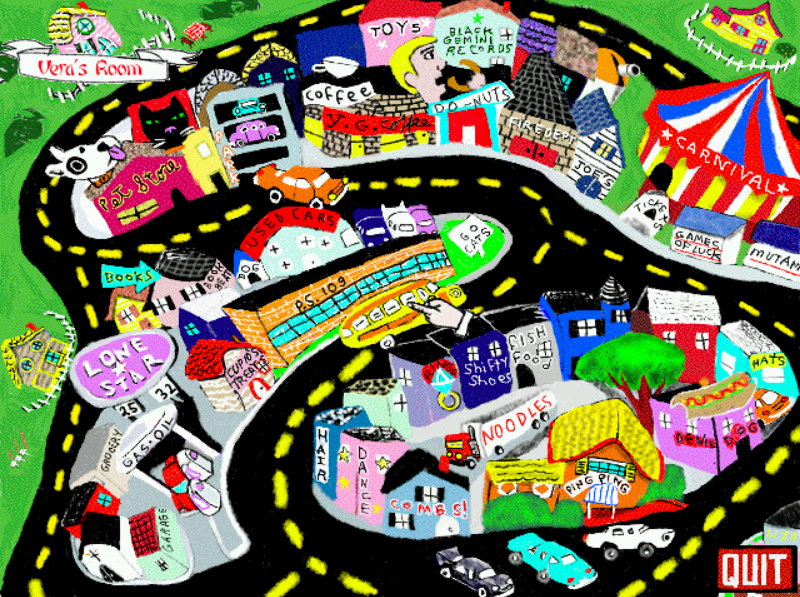

The non-linear game allows players to see through the eyes of tweens Lily and June Bugg, as they explore the neighborhood they call home. The game offers an optional “story on” mode with narration by David Sedaris that shares insights about the space and its residents. The colorful look and feel of the neighborhood, borderline absurd and psychedelic in certain spaces, also integrates photographs, film clips, and a variety of ever-present sound effects so players stay immersed in the world. Odd, original songs pop up in different spaces, courtesy of Brendan Canty, former post-punk Fugazi band member, including “Mud Pup,” a brilliant ode to the local neighborhood dog. The result is a surreal, but warm journey through a neighborhood of a dozen stories. By exploring the sights and sounds of the community—homes, shops, people, pets—players get to peek inside all the highs and lows of everyday life with dashes of make-believe here and there, such as singing pickles and working X-ray glasses.

What Chop Suey captures so well is what William Van Vliet (1983) called the “fourth environment,” spaces of important identity formation and childhood development outside of home, school, and the playground, otherwise adult-regulated and time-structured places. In Chop Suey, players are not able to enter the school or June and Lily’s own home; no playgrounds exist in the neighborhood. Instead, players must explore the community’s fourth environments where the independent tweens make their own play spaces such as a candy shop, a bingo-playing book shop, a visiting carnival, an aunt’s bedroom, and a noodle house where they order the dish from the game’s title. Within any of these spaces are dozens of interactive objects and sounds that peel back the layers and stories of the neighborhood and, most importantly, of its residents.

Influenced by Richard Scarry’s Busytown books and Louise Fitzhugh’s Harriet the Spy, Duncan emphasizes the game’s eclectic cast of characters by making them the focus of the players’ discovery and the tweens’ fascination. In an interview in From Barbie to Mortal Kombat: Gender and Computer Games, Duncan shares that a primary goal was to demonstrate how neighbors (and neighborhoods) are interconnected in the most light-hearted and sometimes messy ways. For example, the tweens encounter several of their aunt’s ex-husbands in the journey of the neighborhood and find old love notes hidden in the aunt’s room. Despite any bittersweet realities, however, the folks of the community are all living their lives and finding joy in their own spaces. Their tales, as well as the tweens’ own journey in the game, are treated as equally important in the immersive story. The game demonstrates that everyone has a story to tell, or as Duncan puts it in From Barbie to Mortal Kombat, “If the memoir of the guy that works in the gas station or the guy with all the tattoos or the story of any of these people is important, then everyone’s story is important.”

As a media historian, I find such joy in playing Chop Suey, because it demonstrates ways we can experience and showcase a community by centering the lives of the inhabitants and their homes. In general, the game celebrates children hanging out and making their own spaces for imagination. As such, replaying the game offers an important reminder: any neighborhood is filled with fourth environments of imagination and play, regardless of its zip code.

If you have never played the game, explore emulated versions of Chop Suey and Duncan’s Smarty (1996) and Zero Zero (1997) through Rhizome, thanks to organization’s conservation efforts and support from many sources including Mary Duncan, original publisher Magnet Interactive, Kickstarter campaign, New York State Council on the Arts, and others.