If you want to be guaranteed a lively conversation, bring up the Ouija board. This polarizing talking board has been around since the late 19th century and still manages to divide people on a number of fronts. Do they truly work? Are they dangerous? Are they a scam? However, the question provoked by its context at The Strong is: Is it a toy?

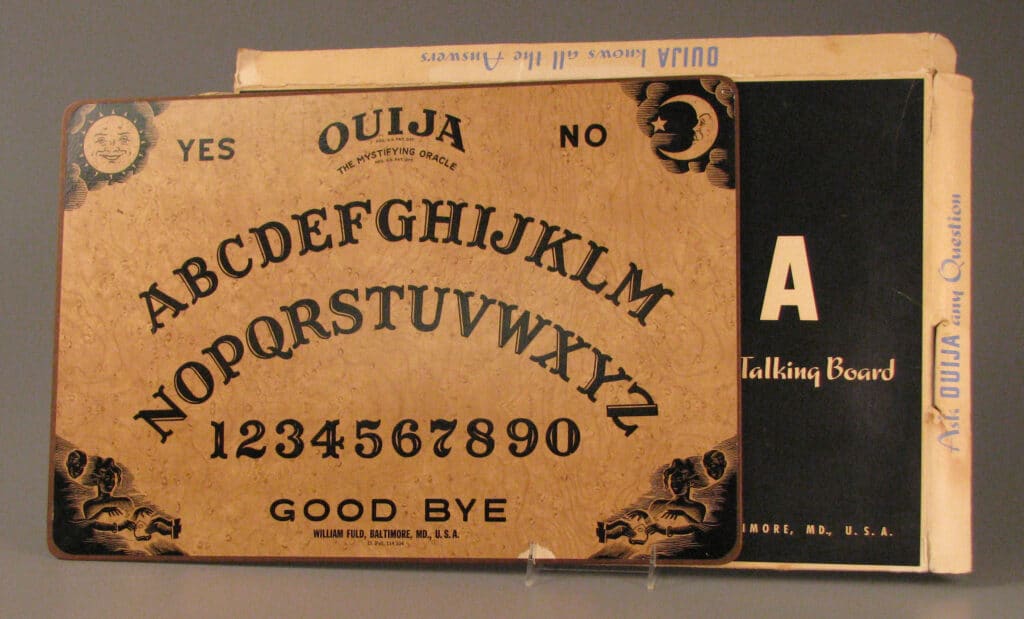

The earliest Ouija boards were produced from a wooden board marked with the letters of the alphabet, numbers, and yes/no choices. A planchette enables the spirits, or the practitioner depending on what you believe, to answer questions. Later the boards were produced on cardboard.

From one perspective, the term Ouija is trademarked by Hasbro, a company known for popular games and toys. Before Hasbro acquired Parker Brothers in 1991, Ouija was produced alongside other famous Parker Brothers board games like Monopoly, Risk, and Clue. Before these companies controlled the name, the Ouija trademark can be traced to William Fuld and the Kennard Novelty Company, which was the first company to produce it commercially.

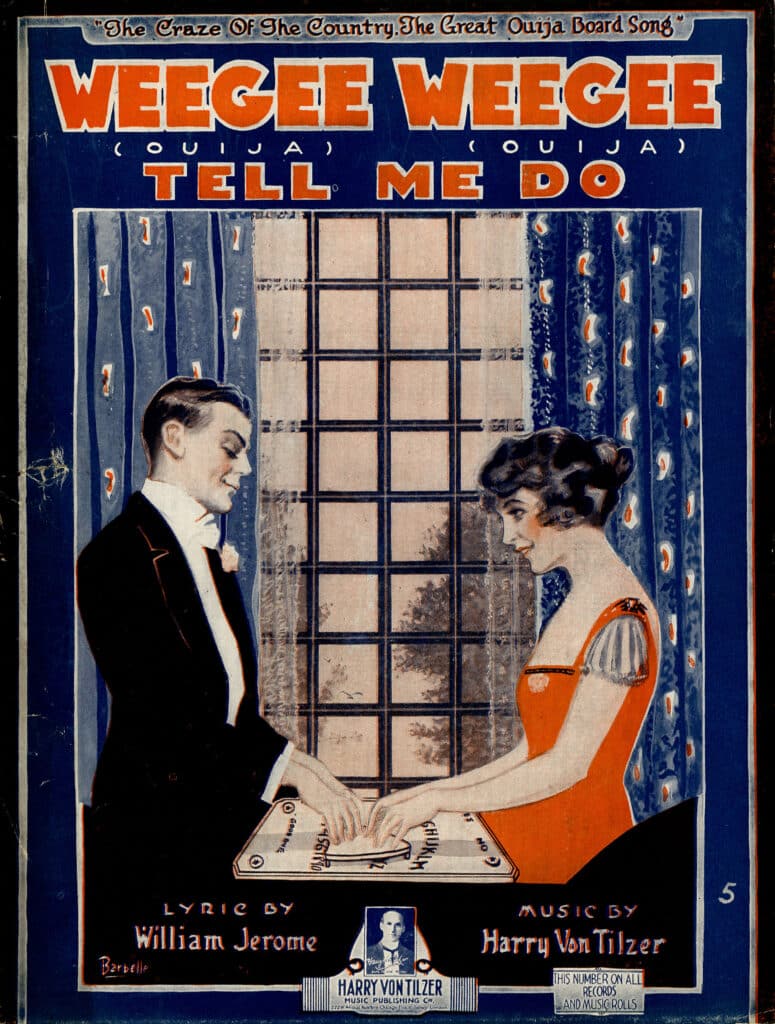

If Ouija is being produced and sold by game companies, wouldn’t that make it a game? There are certainly arguments for it. Many a sleepover is graced by the presence of the Ouija board. It elicits the excitement of dabbling in the unknown or playing tricks on your friends. In addition to being sold alongside board games, it is a social activity, sparks conversation, and encourages strategy (even if that strategy may be subtly moving the planchette yourself). Groups of giggling pre-teens crowded over the board and holding the planchette together certainly reflects what you would expect from a toy.

However, Ouija’s position as a toy is challenged by its origin in spiritual work. Talking boards have roots in a variety of practices around the world and deep into the past. The Ouija board itself is heavily connected to the modern Spiritualism movement in the United States that began with the Fox Sisters and their communications with spirits through rappings. Though many point to Maggie Fox’s confession of a hoax to disprove the sisters’ claims, Spiritualists point out that Maggie was under the pressure of financial circumstances at the time of her confession (a confession for which she was paid) and later recanted it. With the Fox Sisters having lived in Hydesville, now a part of Newark, NY, there is an active community of modern Spiritualists living the legacy of the Fox Sisters in the region around The Strong.

One Spiritualist belief is that living people and spirits can communicate. Mediums act as a conduit for that communication. To many Spiritualists, talking boards, pendulums, tarot cards, and other devices are tools for connecting to spirits, not simply toys, and with this also comes a certain amount of responsibility the practitioner should have. Tracy Murphy, a practicing Spiritualist and the caretaker of the Fox Sisters Property/Hydesville Memorial Park, explains:

“Some Spiritualists will say that using any objects for communication is not necessary, however they have forgotten that although spirit communication came through as rappings in the beginning to Maggie and Kate Fox, it was their brother David that suggested writing letters on paper and calling them out and writing the answers. Personally, at the end of the day, it’s a personal choice. If you have pure intentions and are not harming anyone, who’s to say that communication from a spirit is not what it is supposed to be.”

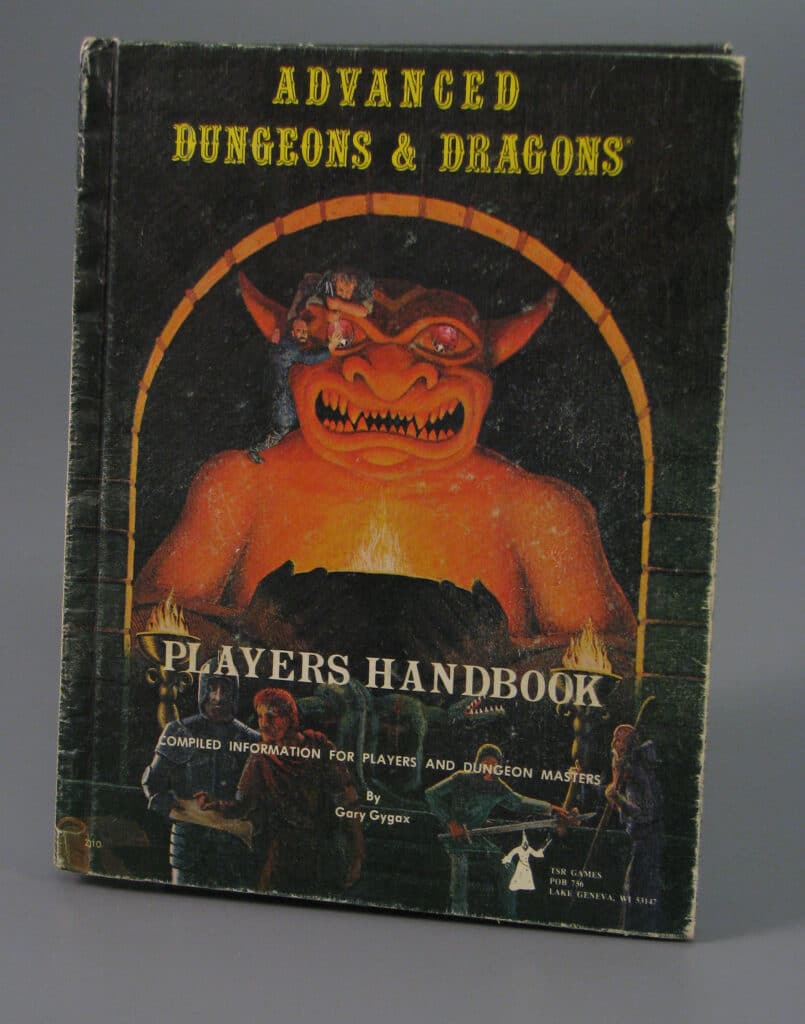

Others take an opposite stance regarding Ouija boards and other divination mechanisms. The 1973 film The Exorcist featured a Ouija board that led to a demonic possession, inspiring many of the occult associations with the board that last to this day. The satanic panic of the 1980s and 1990s didn’t help alleviate any of those concerns. To many, the board is associated with witchcraft, demonic rituals, and evil spirits. The Ouija board has been condemned by many religious groups due to its association with divination, which many believe involves communication with the occult. Other elements of pop culture have also raised such concerns through the years, including Harry Potter, the Magic 8 Ball, and Dungeons & Dragons.

Many skeptics would disagree with all these perspectives and argue that the Ouija board is nothing more than a board. Some would assert that there is always a player that is causing the movement. Others would cite scientific theories like the ideomotor effect, that attributes certain almost subconscious movements to the thoughts and images held in the mind. This concept would explain how movement can happen through the influence of the mind’s own suggestion, short of any deliberate decision on the individual’s part. Skeptics who subscribe to either of these theories could probably argue either side of whether Ouija is a game, even if they don’t believe there are further spiritual implications.

The same question, Is this a game?, could be raised about other childhood games meant to explore “the other side.” Popular at sleepovers is the game Bloody Mary, usually consisting of rhymes spoken in a dark bathroom with the door closed in an attempt to rouse the spirit of the dead woman. Another popular game is Light as a Feather, Stiff as a Board, which thrills the players with the idea of their psychic power helping levitate a friend. Each person uses two fingers to collectively lift a person while chanting the game’s name. Other mysterious, dark, or chilling games abound that walk the line between party game and something more.

Perhaps the answer to the question is subjective. What may be most important is a sensitivity to differing perspectives and acknowledgement that what is a game for one person may be a spiritual practice for another. What may be a silly parlor trick to one could be a dangerous activity to another. Whatever your perspective on the Ouija board and other sleepover staples, a full understanding is rarely so simple as one viewpoint.