Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee….

There was something particularly playful about Muhammad Ali, the boxer who rivaled Pele as the most famous worldwide sports celebrity of the 20th century. But whereas Pele was known for his quiet dignity and his sheer enthusiasm for the beautiful game of soccer, Ali was not only the greatest boxer of his era, he was also a genius of repartee, someone who played with the media like he played with his (usually) helpless opponents in the ring, a fighter who dispensed one-liners and quips with the skill of his lightning-fast left jab.

Ali had a charismatic, magnetic personality. Norman Mailer began his book The Fight about the boxer’s famous 1974 bout with defending world champion George Foreman in Zaire (the so-called “The Rumble in the Jungle”), with this description of Ali:

There is always a shock in seeing him again. Not live as in television but standing before you, looking his best. Then the World’s Greatest Athlete is in danger of being our most beautiful man, and the vocabulary of Camp is doomed to appear. Women draw an audible breath. Men look down. They are reminded again of their lack of worth. If Ali never opened his mouth to quiver the jellies of public opinion, he would still inspire love and hate. For he is the Prince of Heaven—so says the silence around his body when he is luminous.”

Part of Ali’s appeal was his sheer playfulness, a key attribute of charisma. Ali began playing with Foreman, his opponent, even before the match, launching verbal jabs intended to keep his opponent off-balance, mocking him as a “mummy.” There was play here, but also calculation and perhaps a little cruelty (something that was even more apparent in his mean-spirited jibes at his great rival Joe Frazier, someone who never forgave him for the insults).

Once the bout with Foreman began, the play continued, both physically and verbally. Ali danced early, leaning on the ropes when he realized it was an effective way to tire out Foreman. And the whole time, Mailer and others recorded, he taunted Foreman. “Can you hit?” he asked Foreman as his opponent tried to land blows on him. “You can’t hit. You push.” He belittled, hurling jibes in response to his opponent’s jabs. He was like a boy playing a game of the dozens with schoolmates. The verbal volleys played with Foreman’s head, the ridicules as rapid as the punches.

Ali brought the same gift of the gab to his interactions with the press. “I’m the greatest,” he bragged. When Time magazine did a cover story on him in 1963 (when he then went by his birth name of Cassius Clay, which he later rejected as his “slave name”), the publication printed a rhyme he had reeled off about himself:

This is the story about a man

With iron fists and a beautiful tan,

He talks a lot and boasts indeed

Of a powerful punch and blinding speed.

He refused to be pigeon-holed by reporters, telling them, “I don’t have to be what you want me to be, I’m free to be who I want.” He knew their game and played it better than they did.

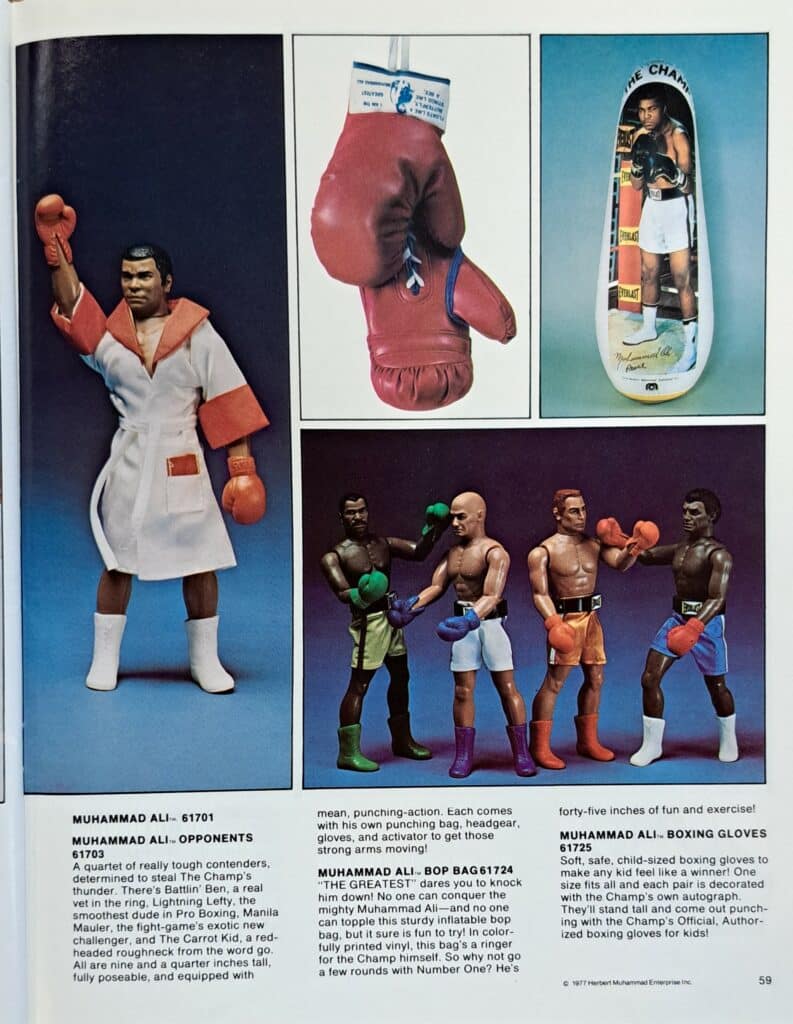

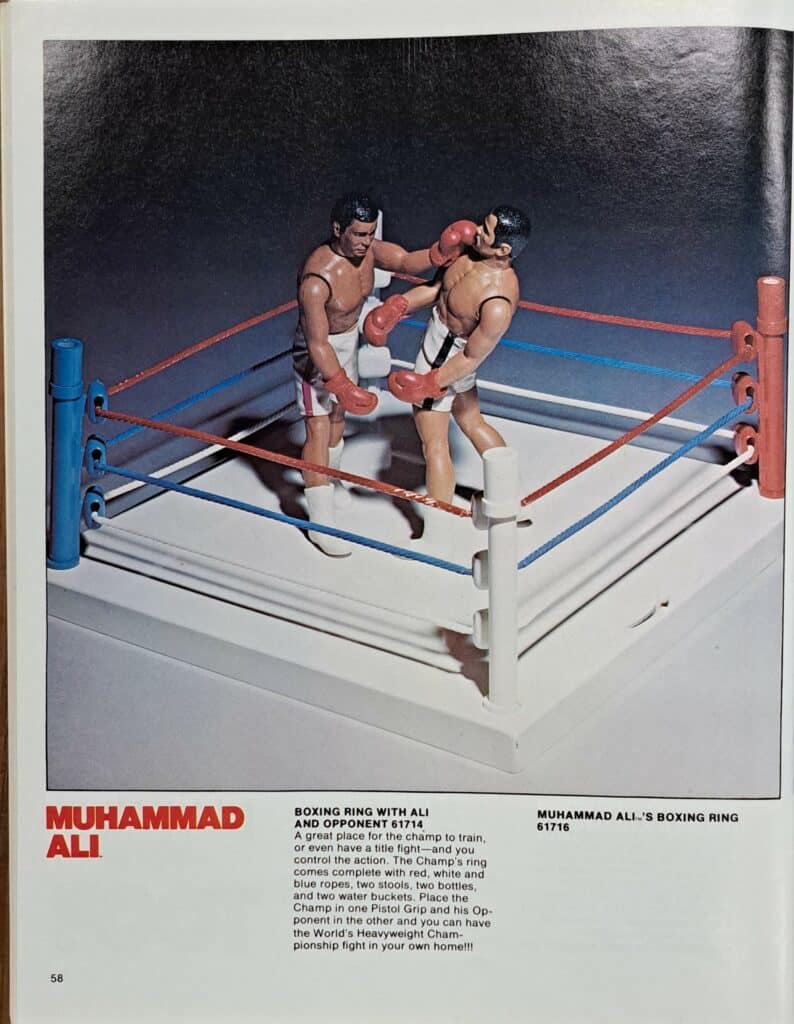

The Strong’s collection highlights how Ali’s celebrity status gave plenty of opportunities for playthings themed around his likeness and image. A Rope-A-Dope jump rope came out in 1977, autographed and endorsed by the champion himself. The Mego Corporation that same year released a line of Ali action figures, complete with fierce but ultimately doomed opponents and a boxing ring to stage a pretend fight. But my favorite Ali item in our collection is probably Stern’s 1980 Ali pinball machine, the second pinball machine to be based on Black celebrities (after the Harlem Globetrotters pinball from the previous year).

There is something appropriate about a Muhammad Ali pinball machine. The way the ball bounces off the electric bumpers feels like the ways that Ali deflected the force of his opponents’ punches back at them. When the game’s not being played, the attract mode sends an audible shiver through the game and when the lights flicker you almost feel like the champion has touched you with a light punch, daring you to take him on.

Ali’s image is everywhere, appearing six times on the back glass and more on the board, including right in the center where his right forefinger jabs towards you, taunting you, “I am the Greatest.” In the game, the kickers are labeled left jab, right cross, and uppercut, and “rope-a-dope” is the upper target that takes the force of your shot and sends it hurtling back at you. Across the bottom, the player is reminded he is “3 Time Champ” and winner of the “Triple Crown.” Players magnify their points when they light up the letters A-L-I and earn an extra ball when they spell out G-R-E-A-T-E-S-T, right below the words “I AM THE”—there’s no shortage of playful braggadocio here.

But I couldn’t just look at the game, I had to play it. My game didn’t start well, as my first ball drained almost immediately (this was back in the unforgiving days of pinball when you didn’t restart your ball if you died too soon). In the end, I scored 106,850, not earning an extra ball or lighting up all the letters for GREATEST. My second game was better, 371,250. And as I played, I almost began to personalize my experience. Imagining my shots at the center bumpers as body blows against my opponent, racking up points (like in a boxing match) but always setting myself up for the possibility that the ball would careening back at me while I was fighting up close and my fists were down, landing like an unobstructed right hook to my jaw.

Like most of Ali’s hapless opponents, I was doomed to lose. And yet when I played, I felt myself absorbing some of his magic and grace. I was playing against him, but also playing with him. And, of course, anyone who dropped in a coin was being played by him (and Stern and the establishment that owned the pinball machine). It didn’t matter. The opportunity to go toe-to-toe with the champ was worth the money, for rarely have there been people in American history who so embodied the spirit of play as Muhammad Ali.

He was the greatest.