We’ve recently opened Skyline Climb, a high adventure ropes course that soars high in our cathedral-like glass atrium. Physical play like this is important, not only as part of the museum experience here at The Strong but as a contributor to well-being in general, especially for children. This attraction offers guests more than just the opportunity to test their agility and balance; it also is a playground for building resolve, courage, and confidence. Asking guests to navigate narrow beams at great heights challenges them to take a risk, and risky play is a vital, yet often unappreciated, form of play.

Before touting the benefits of risky play, however, it’s useful to point out the difference between risky play and dangerous play. Truly dangerous play involves major damage to life or limb; just because someone scrapes a knee or bangs a shin doesn’t mean what they were doing was actually dangerous. Some dangerous situations may not even look risky—traversing a snowy mountain field may look perfectly safe, but in fact there might be a high probability of a deadly avalanche. In built structures, true dangers usually come from neglect or poor design. Broken glass left on a playground or a bolt protruding in a fall zone—those are both examples of hazards that should be avoided. Good design doesn’t mean removing anything that has the least possibility of causing injury; it means removing things that could cause serious harm even if the person is taking reasonable precautions.

Life is full of risks, and we only develop physically, emotionally, and intellectually if we take risks. Consider a toddler learning to walk. When she is taking her first hesitant steps there is a high risk that she will fall, perhaps experiencing enough surprise or pain that she begins to cry. What do we do? We comfort her and encourage her to try again, to risk walking again, even if she goes down again… bump. We also evaluate the environment to make sure there are no physical features, like the sharp glass edge of a coffee table that could cause grave injury. Aside from that, however, we know that learning to walk takes risks, and she, like most children, enjoys the feeling of accomplishment that comes from taking a risk and succeeding. Those first steps feel glorious!

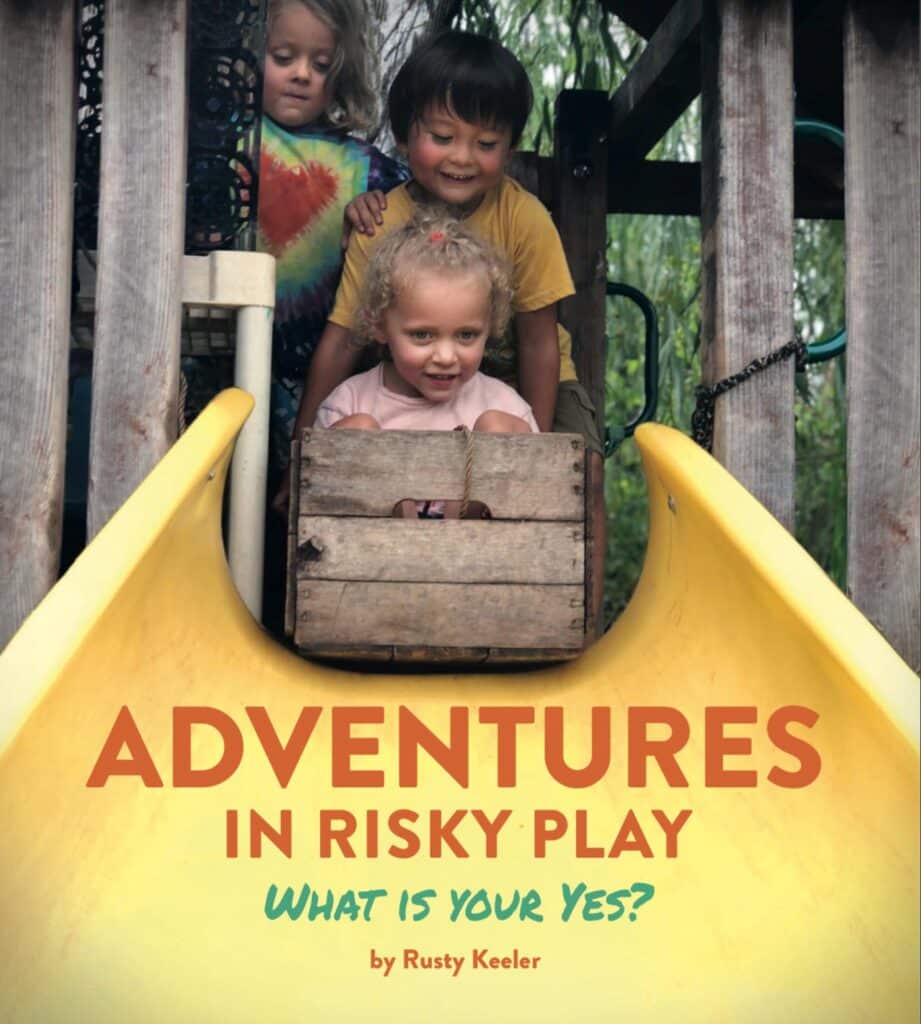

There is a temptation in modern life to remove as much risk as possible, to make living safe and anodyne. Some of this is cultural. In an article published in The Strong’s American Journal of Play, authors Ellen Beate Hansen Sandseter and Ole Johan Sando noted that adults in Scandinavia, Italy, and elsewhere in Europe are much more comfortable with letting young children go out and play unsupervised in nature than are American grown-ups. But as Rusty Keeler points out in his book Adventures in Risky Play, when we remove risk, we also hinder growth, for almost no growth comes without risk. And removing risk is often short sighted, minimizing our trust in individuals to rationally make decisions about how to handle reasonable levels of risk.

Children engage in risky play because they enjoy it. There’s a thrill that comes with facing danger and overcoming it, of confronting a physical challenge and surmounting it. In life, when we derive enjoyment from some activity, we likely also gain benefit from it as well. Sandseter and Sando note several benefits that seem to accrue from taking part in risky play. First, engaging in risky play helps children overcome anxieties, such as fear of heights. Second, children become more skilled risk-takers. This seems to reduce long-term injury rates, probably because the children are more agile and coordinated and also more skillful at assessing risk. If you’ve climbed a tree before, you’re better positioned to determine how high you can safely go, how best to get good handholds and footholds, and how to descend safely.

What implications does this have for us grown-ups? One, when adults are caring for children, either as parents or caregivers, they may be wise to give children scope to play more freely, to take more risks. It’s likely ok if they fall off while trying to balance on a log. Watch them. They probably will get right back up and try again, experiencing that rush of delight when they successfully walk across. And the same is true for us in our own lives. We need to give ourselves permission to take risks and, perhaps, fail. It’s ok, we can always get back up and try again.

Time to go take a climb on that ropes course!

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.