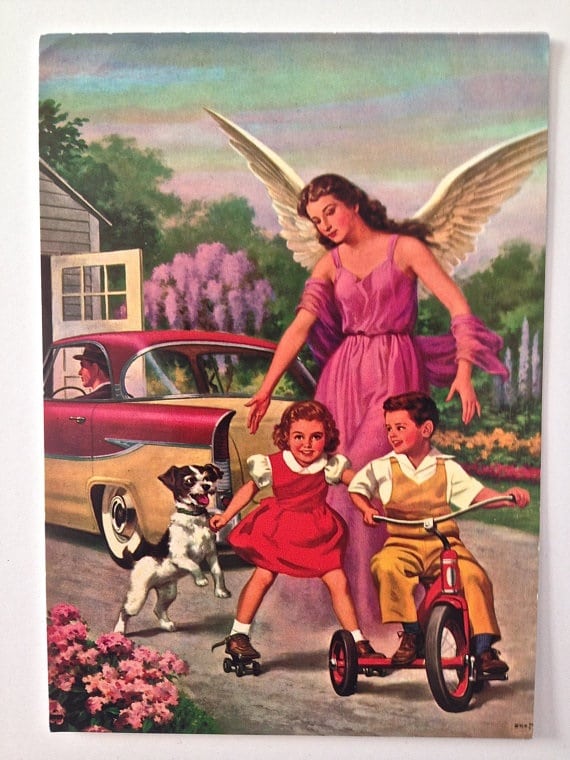

A friend sent me this striking image a collector had reproduced as a postcard in 1993, and titled “Angel of the Asphalt: A Miracle on Maplewood Drive.” The attribution on the back guessed its original date at 1954. Irony had accumulated over those four decades between the original and the reproduction. The collector, in a skeptical, post-modern spirit, meant the copy to evoke and poke fun at a hokey, bygone ideal.

I couldn’t take my eyes off the image. The picture begged to be located, read, and interpreted.

First I considered the problematic date, 1954. Surely that was wrong by several years. Yes, the car’s two-tone paint job came near enough to those big post-war coupes, though yellow and red was unusual. The car pictured also appears to have no back seat. But the telling point is that no car sported such prominent fins in 1954. To me it looked mostly in the way of a ’57 or ’58 Plymouth, when American automobile designers had begun to think “rocket cars” whenever they stamped sheet metal. On this 50s dream-car the fins curved inward, though, trunk-ward against both an aerodynamic principle and my Plymouth memory.

Then there was the image itself, which the collector in his reproduction identified as a “calendar graphic.” This description also seemed puzzling and wrong because illustrated calendars meant to hang in the kitchen almost always ran horizontally to accommodate seven days across. To me, instead, the dimensions and vertical orientation recalled a “holy card”—the kind that baby-boom era nuns gave us as rewards for volunteering to clean classroom erasers after school. With a little digging and asking around, that’s where the image proved to have originated. The playful scene was like nothing I’d ever seen pictured on a holy card.

Its imagery depicts a grouping of five figures—a dad in the driver’s seat, the frolicsome mutt ready to play, the merry brother riding a trike looking blithely to his right toward his sister, and the sister on roller skates, feet splayed and a little unsteady. All of them are at risk for a dangerous moment. Above floats the presiding, shepherding angel, interposing and ushering the kids away from hazard. Perhaps the angel also reminded the driver to look into his rearview mirror.

Surprisingly it’s not the guardian angel who dominates the scene with her protective gesture; it’s the young girl. The daughter compels our attention and composes this cautionary tale merely with the look on her face. Her expression mixes pleasure and sudden recognition, an incipient, growing fear hinted at in her dulled right eye. She displays a grin on its way toward a grimace (cover half her face at a time and you’ll see what I mean). At this moment she seems to be discovering a danger that approaches not from behind her but from the front, onrushing, from out of the frame. It is her danger to face. She stares directly outward at us, the viewers, as if we are the ones approaching in another car.

In that era before mandatory seat belts and on-board backup cameras, the guardian angel, though powerful, was not making any move to absolve drivers of a need for caution. Most of us can look back and with good reason wonder how we ever survived our childhoods. This picture came from an era more of moral watchfulness than parental vigilance about safety. Minute to minute, they left more to fate than we do now. And so for the children on wheels left mostly on their own, parents would explicate this card with an unambiguous message: “the life you save may be your own.” It’s here that the prayer-card image drives us back to the historical context of its creation, the 1950s suburban neighborhood that overflowed with frisky dogs and playful kids in motion in the driveway or the street who stood not much taller than the bumpers of those lumbering, stylish cars.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.