If you’re the right age and you spot Sixfinger among other Cold War spy toys on the museum’s second floor, it will bring back a flood of memories.

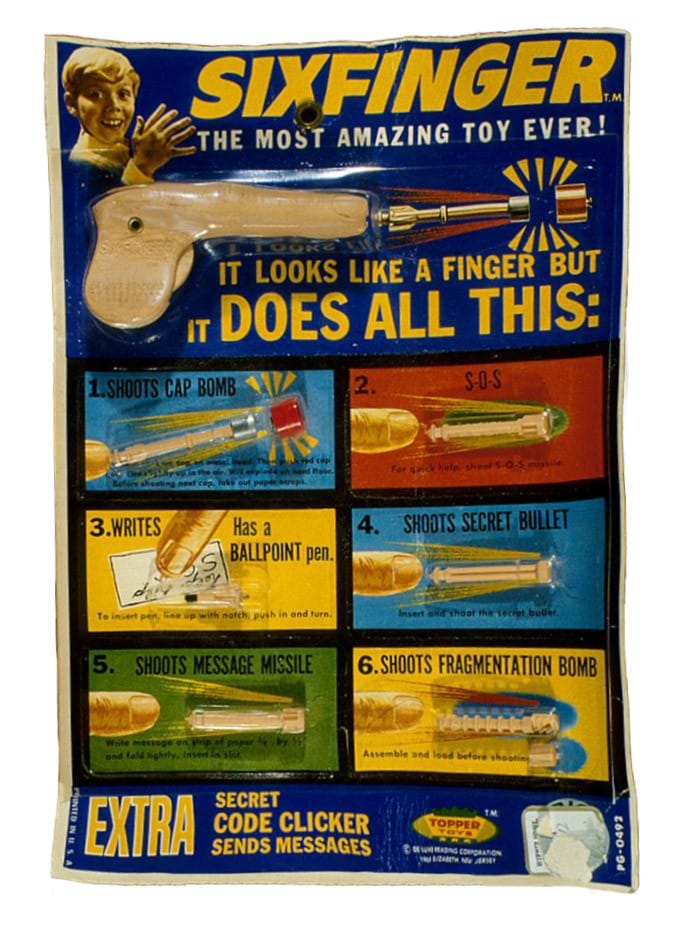

I was too old in 1965 to have owned the Sixfinger toy, but not too old to be intrigued by the fantasy behind it. From movies and TV shows like Man from U.N.C.L.E and Secret Agent, we knew that a spy’s kit was always concealed in everyday things, and what could be more ordinary than a fake digit? So why not Sixfinger? It sure would be handy against the Cold War villains who seemed to lurk everywhere. Sixfinger boasted more features than a Swiss Army knife. Shaped as an index finger—an extra index finger meant to be held between thumb and forefinger—Sixfinger concealed a cap-loaded grenade launcher, a signaling device, a pen to write the coded messages that would travel via a tiny “S-O-S missile,” and a “secret bullet” for tight spots. What counterspy could possibly spy it while searching for the tear gas in the shaving cream dispenser, the microdot in the diary, or the phone in the shoe? I mean, who’s counting fingers?

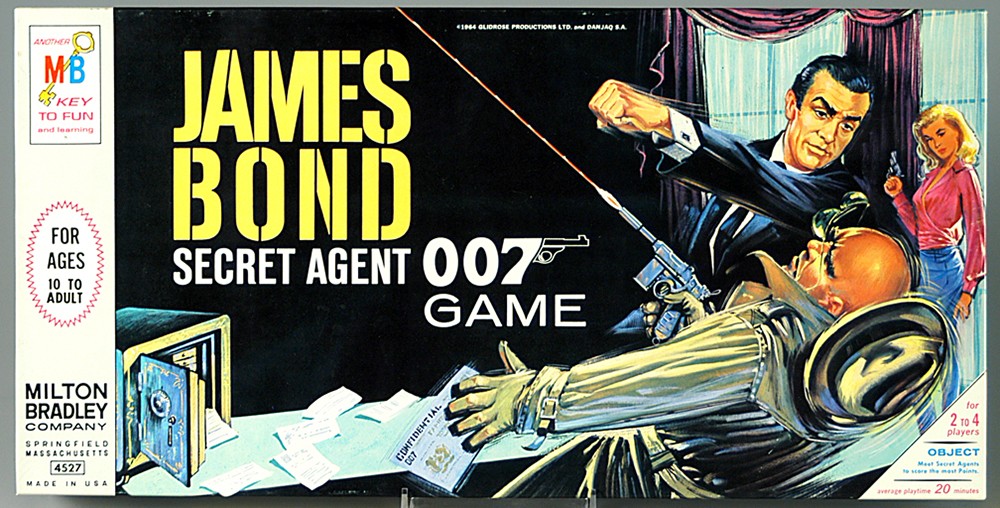

You can’t think about Sixfinger without thinking about James Bond. During the mid-1960s, just past the frostiest point in the Cold War, many boys saw Bond as a kind of superhero who got his powers from clever weaponry. But does it follow that these ingenious gadgets were toys? James Bond took some heat for thinking so. In a set piece that appears in many of the films, Bond meets Q, the head of Her Majesty’s secret service research and development branch, and earns a rebuke for clowning around with the technology:

Bond: “Ejector seat? You’re joking!”

Q: “I never joke about my work, 007.”

Bond, suave, charming, and ironic, was playful in the face of danger in a way that the responsible technology guy couldn’t be. Cheekiness was one of the reasons that audiences found Bond so engaging.

The gadgets that made Goldfinger, the second Bond film, so memorable and entertaining included a snorkel disguised as a duck, two homing devices, a bulletproof coat, and of course the steel-rimmed bowler hat that Goldfinger’s valet, Odd-Job, sent sailing. Sixfinger, which sort of rhymed with “Goldfinger” and followed the movie by a year, was kin to these fictional gizmos in an era when fiction and fact were not so separate. Ian Fleming, James Bond’s creator, had served as a British counterespionage agent during World War II, cooking up scenarios so complex and audacious that they made the plots of his novels seem ordinary. Sixfinger was not far in concept from real life Cold War spy-armaments like the exploding cigar that the CIA designed but never deployed to eliminate Fidel Castro, the poison-tipped umbrella that KGB agents used to assassinate a Bulgarian dissident, or the combat knives that military engineers concealed in pancake flippers. The Cold War was no joke.

A last word about toy advertising. In the mid-60s we learned to want Sixfinger, “a secret weapon at your fingertip,” from insistent, rhyming, 60-second, television commercials. “Looks like a finger so no one can see. Who has Sixfinger? Me! Me! Me!” We’re used to 15-second spots now, and if you watch the vintage Sixfinger ad, the jingle will seem to go on forever. But stick with it and you’ll learn a good deal about this fascinating toy, the way kids used play to deflect the fears of the day, and how toymakers sold us stuff. With the last line of the jingle smart marketers managed to turn a luxury—a sixth finger for Pete’s sake—into a necessity: “Sixfinger, Sixfinger, man alive! How did I ever get along with five?”

By Scott Eberle