I arrived at The Strong National Museum of Play near the end of January 2024 with nine days to spare to submit a book manuscript and a Research Fellowship lasting just five days. This, then, would not be a luxurious waltz around the vast collection in the archives. It was more a sprint through I had already reconnoitered titles in the hope of verifying previous leads, and tidying up some loose ends in some previously written chapters.

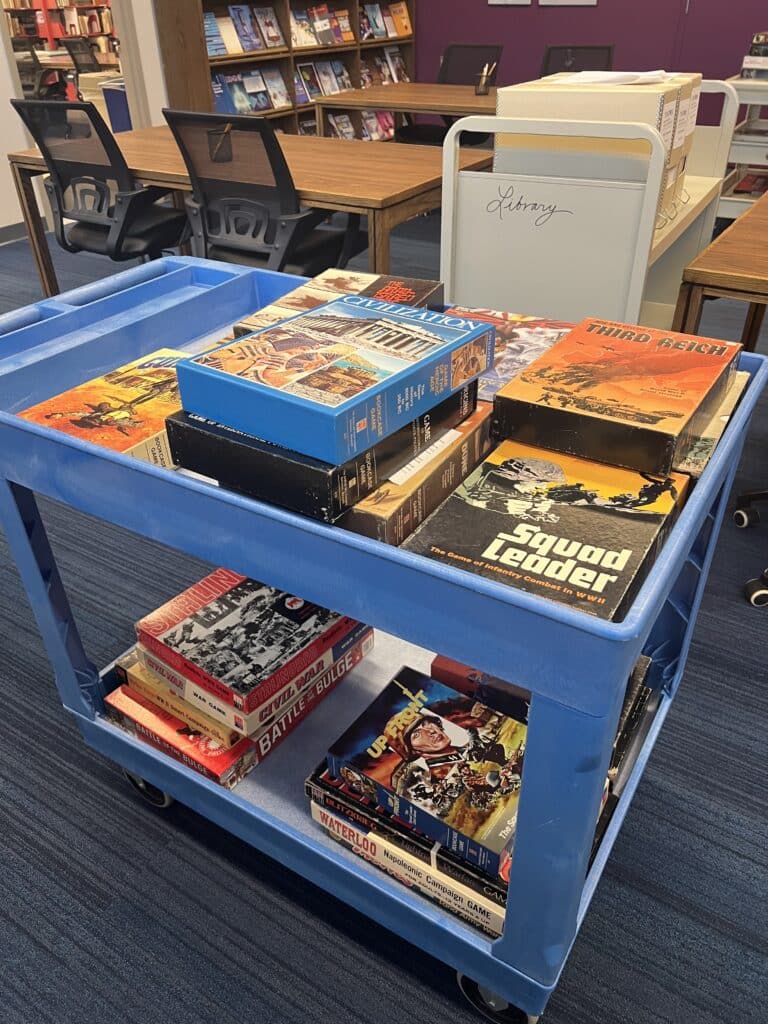

This book is about historical board games—that is games with their settings in history, rather than games that are exceedingly old. Most of the games I was researching range from the 1960s through to the early 2000s. These games largely fall within the definition of board wargames, predominantly published by Avalon Hill and SPI (Simulations Publications Incorporated). They explore topics in military history—often World War II and the American Civil War—and are generally printed on thick cardboard boards with many hundreds of small cardboard pieces as well as rulebooks with combat results tables (CRTs).

What I learned was this:

Thing #1

A lead I had on the game The Arab-Israeli Wars: Tank Battles in the Mideast (1977) turned out to be false. There was no chit pull mechanic in that game. I suspected as much; BoardGameGeek (BGG) had given no such indication. Even so, I wanted to be thorough.

Thing #2

I learned that Gunslinger (1982) was not the game I was thinking of. I was looking for a Wild West gunslinger game with a trap door component. Again, BGG had given me no reason to think it was in this game, but I wondered if there was something buried in the box that would explain why I had a memory of such a component from a game with the same historical setting and published around the same time. There was not. I had misremembered the game, but I don’t think I imagined the game out of nowhere. So the search for that particular game and its specific component continues.

Thing #3

I learned that the board for James Dunnigan’s The Origins of World War II (1971) looked prettier (excluding the placement of the USA) than I had realized. It has a cartographic detail that, to me, gives the game a sense of gravity.

Thing #4

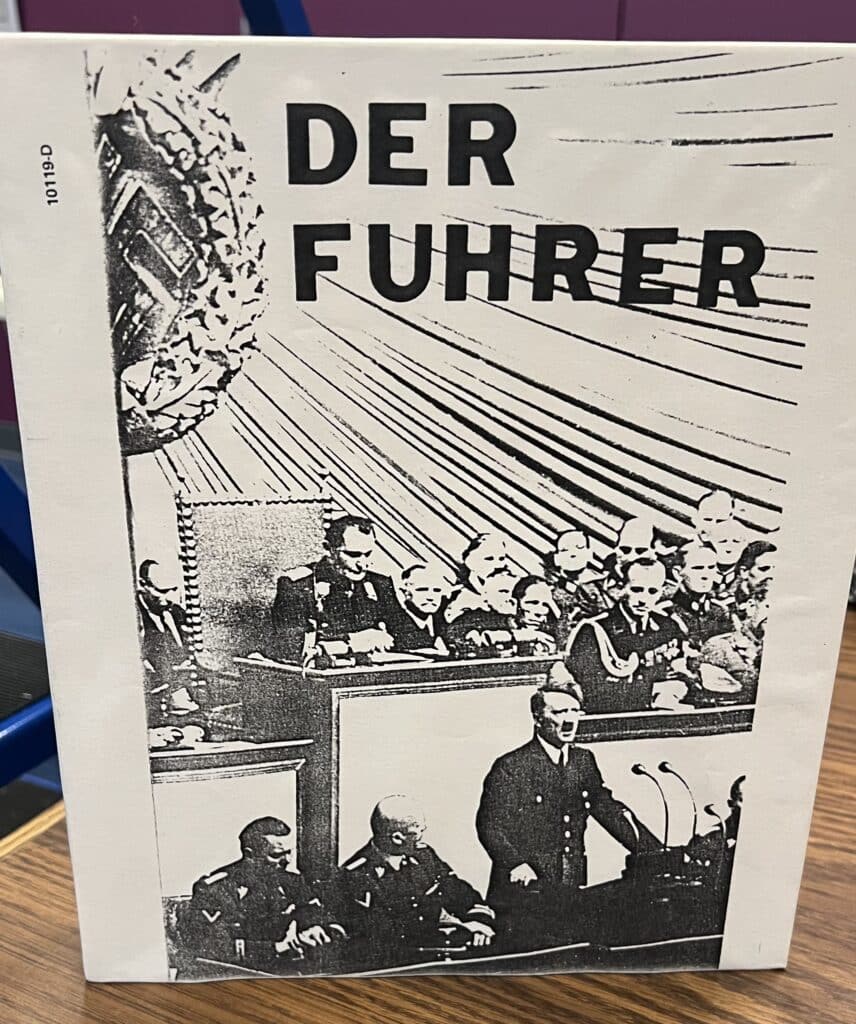

I learned, through Jeremy Best, a history professor at Iowa State and fellow researcher in the same field who was at The Strong Museum at the same time, of the existence of a game called Der Fuhrer (1976). Jeremy had it on his desk opposite to me and asked if I knew about it. It was new to me. It is a game about political conflict—about winning elections—in 1930s Germany. It is not the first election game, which appears to be Mr. President (1967 & 1971), not to be confused with games of the same title published in 1960 and 1965, which were trick taking and highest card wins games with no significant simulation value. Der Fuhrerdoes appear to be the first commercial release of a game on German politics in the 1930s, a precursor to two far more recent games, Weimar: The Fight For Democracy (2023), and The Weimar Republic: Political Struggle in Germany, 1919-1933 (2024) about interwar German politics and paramilitary control. I checked in with my friend, Matthias Cramer, designer of Weimar: The Fight For Democracy, curious to see if he had heard of Der Fuhrer. -He had not.

Thing #5

In fact, Jeremy’s presence and his intersecting research interests also taught me that analog games, and analog wargames dating back to the 1950s may be enjoying a surge of more scholarly interest than they have hitherto experienced. Aaron Trammell’s Privilege of Play (2023), a book about geek culture and white masculinity is another title that engages with historical board wargames, demonstrating evident recent interest in this space. Indeed, Analog Game Studies, the journal where Aaron is Editor in Chief is also an indication of this interest. (We could cite Jon Peterson’s Playing at the World from 2012 too.)

Thing #6

Wandering through parts of the exhibition space, I noticed a game on display that I only partly recalled from TV ads in my youth. Dark Tower (1981) is a fantasy quest board game with a large electronic (battery-operated) tower sitting in the middle of the board. The utility of this tower—apart from its marketing gimmick and significant material presence—is that it helps, amongst other things, to facilitate battle resolution and track food storage, as well as playing music at significant moments. The game is of interest to historians of games because it has a legitimate claim as a precursor to the hybrid digital-analog designs we now see in games such as Mansions of Madness (2nd edition) (2016), Detective: A Modern Crime Board Game (2018), and Chronicles of Crime (2018). These games integrate digital elements to help tutorialize and/or ease the administrative burden of playing the games, but also allow some of these games to be playable at all, managing the regulated release of hidden information through inaccessible databases.

Thing #7

The final thing I learned, which I learned closer to the beginning of my visit than the end, is that next time I come here I will come for longer and with a more open-ended research agenda.

By Maurice Suckling, 2024 Mary Valentine-Andrew Cosman Research Fellow

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.