It’s hard to believe that Sesame Street is turning forty. But then again, it’s also hard to believe that Sir Michael Philip “Mick” Jagger, another 60’s figure, is old enough to qualify for a British “old age” pension. Sesame Street has aired long enough for its viewers now to include great-grandparents and great grand-children.

It’s hard to believe that Sesame Street is turning forty. But then again, it’s also hard to believe that Sir Michael Philip “Mick” Jagger, another 60’s figure, is old enough to qualify for a British “old age” pension. Sesame Street has aired long enough for its viewers now to include great-grandparents and great grand-children.

Way back before Sesame Street, “educational television” usually meant Sunrise Semester—a six a.m. televised college lecture that was so tiresome that it made you want to crawl back into bed. In this era, kids lived mostly on a meager television diet of cartoons, cartoons, and more cartoons. But a gutsy young documentary producer from New York named Joan Ganz Cooney noticed how closely kids paid attention to commercials in forgettable shows like Batfink and Super President. And, since kids were paying attention so carefully, she posed a mischievous question: why couldn’t a television program for kids entertain and educate? The answer seems so plain to us now, as young Sesame Street watchers regularly point out that the goal post looks like a Y or that tires look like Os. But before Sesame Street, the answer wasn’t so obvious.

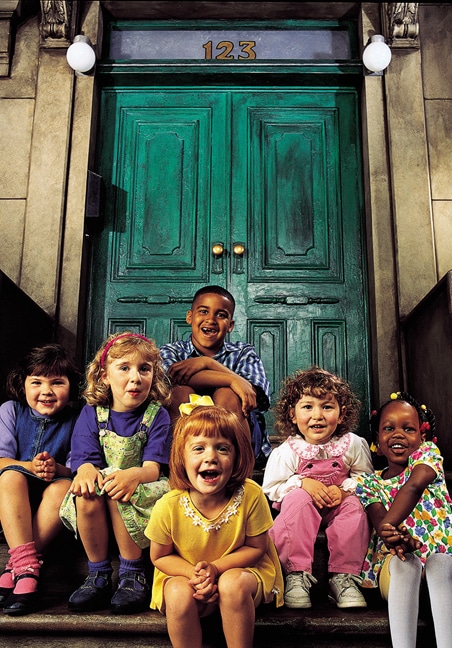

Cooney’s question came at an urgent moment, too. Riots had recently torn through American cities; in their wake many blamed a failed educational system that fed a cycle of poverty, crime, and urban decay. Could “mainstream” teachers ever be much help to “minority” students in this climate? Thoughtful people often thought not. But Cooney brought together a can-do group of producers, educators, evaluators, policy makers, funders, and Muppeteers in 1967 to find a way to “stimulate the intellectual and cultural growth of young children—particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds.” Their “Children’s Television Workshop” decided that television could prepare kids to learn to read and do math, and this hot idea attracted more than five million dollars in pledges for start-up costs.

Cooney’s question came at an urgent moment, too. Riots had recently torn through American cities; in their wake many blamed a failed educational system that fed a cycle of poverty, crime, and urban decay. Could “mainstream” teachers ever be much help to “minority” students in this climate? Thoughtful people often thought not. But Cooney brought together a can-do group of producers, educators, evaluators, policy makers, funders, and Muppeteers in 1967 to find a way to “stimulate the intellectual and cultural growth of young children—particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds.” Their “Children’s Television Workshop” decided that television could prepare kids to learn to read and do math, and this hot idea attracted more than five million dollars in pledges for start-up costs.

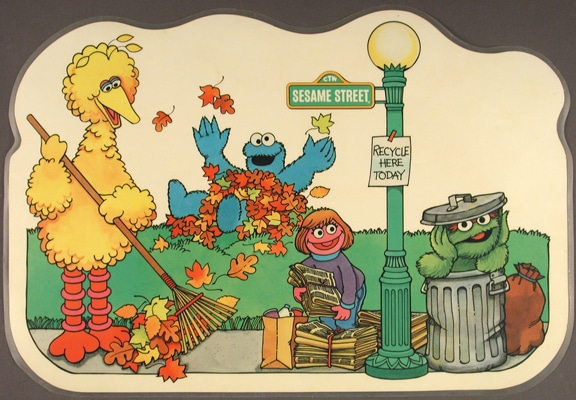

Jim Henson’s Muppets helped Sesame Street debut with critical acclaim by transforming curriculum into comedy. Bert, Ernie, and Oscar the Grouch are familiar faces now. Big Bird helped the youngest viewers understand their feelings. Count von Count, recruited to help kids with numbers, counted everything in sight. “I vant to count your neck,” the Count would say in his distinct Transylvanian accent, “Vun neck!” And the original animations, on view in the museum’s popular long-term exhibit Can You Tell Me How to Get to Sesame Street? remain surprisingly fresh after forty years.

Jim Henson’s Muppets helped Sesame Street debut with critical acclaim by transforming curriculum into comedy. Bert, Ernie, and Oscar the Grouch are familiar faces now. Big Bird helped the youngest viewers understand their feelings. Count von Count, recruited to help kids with numbers, counted everything in sight. “I vant to count your neck,” the Count would say in his distinct Transylvanian accent, “Vun neck!” And the original animations, on view in the museum’s popular long-term exhibit Can You Tell Me How to Get to Sesame Street? remain surprisingly fresh after forty years.

Back in 1970, Children’s Television Workshop set up field offices in America’s inner cities and impoverished rural areas to coordinate outreach to parents and kids and recruit viewers. At about a penny invested in each pair of eyeballs per program, this paid off. By 1973, Sesame Street was reaching 97 percent of Chicago households with preschoolers. And, by 1978, the show was reaching more than 90 percent of inner-city preschoolers nationwide. Pollsters declared that Sesame Street had become “an institution with ghetto children” and research proved that the more children watched, the more they learned. Also, the more they watched the show with their parents, the more the curriculum sank in.

Over the years, celebrity guest stars helped keep adults watching alongside. Bill Cosby put in cameo appearances, as did Billy Crystal, Rosemary Clooney, Stevie Wonder, The Dixie Chicks, Hillary Clinton, and Yo-Yo Ma. Ray Charles memorably sang the alphabet song. Patti LaBelle sang “How I Miss My X,” and Jeremy Irons croaked out, “You Have to Put Down the Ducky to Play the Saxophone.”

Over the years, celebrity guest stars helped keep adults watching alongside. Bill Cosby put in cameo appearances, as did Billy Crystal, Rosemary Clooney, Stevie Wonder, The Dixie Chicks, Hillary Clinton, and Yo-Yo Ma. Ray Charles memorably sang the alphabet song. Patti LaBelle sang “How I Miss My X,” and Jeremy Irons croaked out, “You Have to Put Down the Ducky to Play the Saxophone.”

We’ve come to count on and live by the assumptions central to Sesame Street—that education will entertain us, that our country is rightfully and naturally multicultural, that women and men are equal, that children can learn despite disadvantage, that early education is crucial, and that kids can begin to master the hard lessons about life.

We’ve come to count on and live by the assumptions central to Sesame Street—that education will entertain us, that our country is rightfully and naturally multicultural, that women and men are equal, that children can learn despite disadvantage, that early education is crucial, and that kids can begin to master the hard lessons about life.

Cooney’s idea became an enduring success. International versions of Sesame Street have carried this optimistic, decent American message to more than 140 countries. But it is unlikely that Sesame Street could emerge again. Imitators multiply, but they can never recreate the atmosphere that nurtured this program. After four decades, Sesame Street still remains fresh, funny, idealistic, kind, optimistic, stimulating, generous, measurably useful, and fun.