A crack of thunder. The rattling of chains. Roars of monsters in the depths. A song to guide your way. These words stoke our imaginations and illustrate how stories are told via the evocation of sound. When people imagine playing a tabletop role-playing game (TTRPG) such as Dungeons & Dragons, they envision people in costume rolling dice, moving small, hand-painted figurines, and navigating sprawling maps of the dungeons that are being delved.

In addition to these material components, however, at the root of every TTRPG experience are stories created by the players and sonic performances that happen as a result. In tabletop role-playing games, sound and story are inseparable. The players at the TTRPG table must evoke worlds, actions, and people through description—recounting what is seen, experienced, and heard within the theater of the mind.

Thanks to the generosity of The Strong National Museum of Play, I was awarded a Valentine-Cosman Research Fellowship. With this fellowship, I was able to spend two weeks going through The Strong’s extensive collection of TTRPG artifacts and associated archival documents in the Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play to support my dissertation research on music and sound within TTRPG communities. What I found during my time demonstrated how sound and music has spurred creativity, conveyed literary genre, and inspired storytelling among both TTRPG writers and players since the inception of the genre.

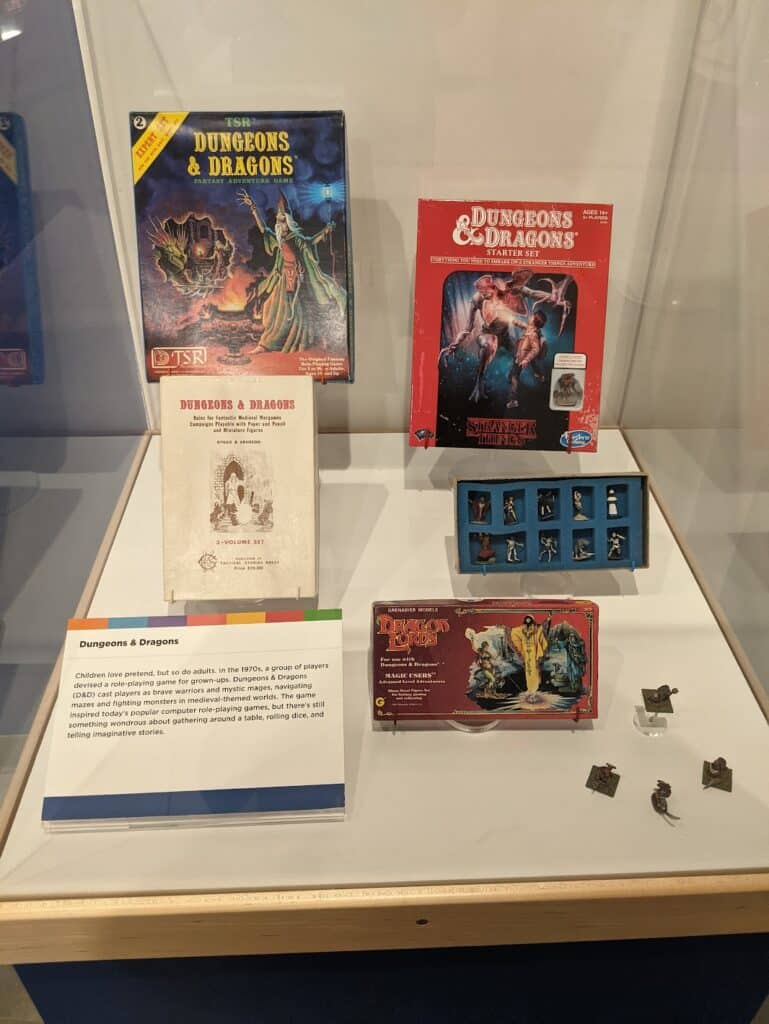

The vast collection of TTRPG sourcebooks at The Strong includes games that span five decades of TTRPG play and cover the gamut of literary genres, ranging from the ubiquitous Dungeons & Dragons (1974) to obscure titles such as Woof Meow (1988). These books serve as manuals on the rules of play, “how-to guides” for acting as a character, and as primers for creative writing and sonic performance. In most of the books I examined, the designers of these games emphasized the need for dramatic storytelling. In a playtest copy of Dungeons and Dragons for Beginners (1979), Gary Gygax and Eric Holmes describe “Dungeon Mastering as a Fine Art,” that laid out the needs for theatrics:

“Dramatize the adventure as much as possible, describe the scenery, if any. Non-player characters should have appropriate speech, orcs are gruff and ungrammatical, knights talk in flowery phrases and always say “thou” rather than “you.” … The dramatic talents of the Dungeon Master should be used to their fullest extent. It adds to the fun.”

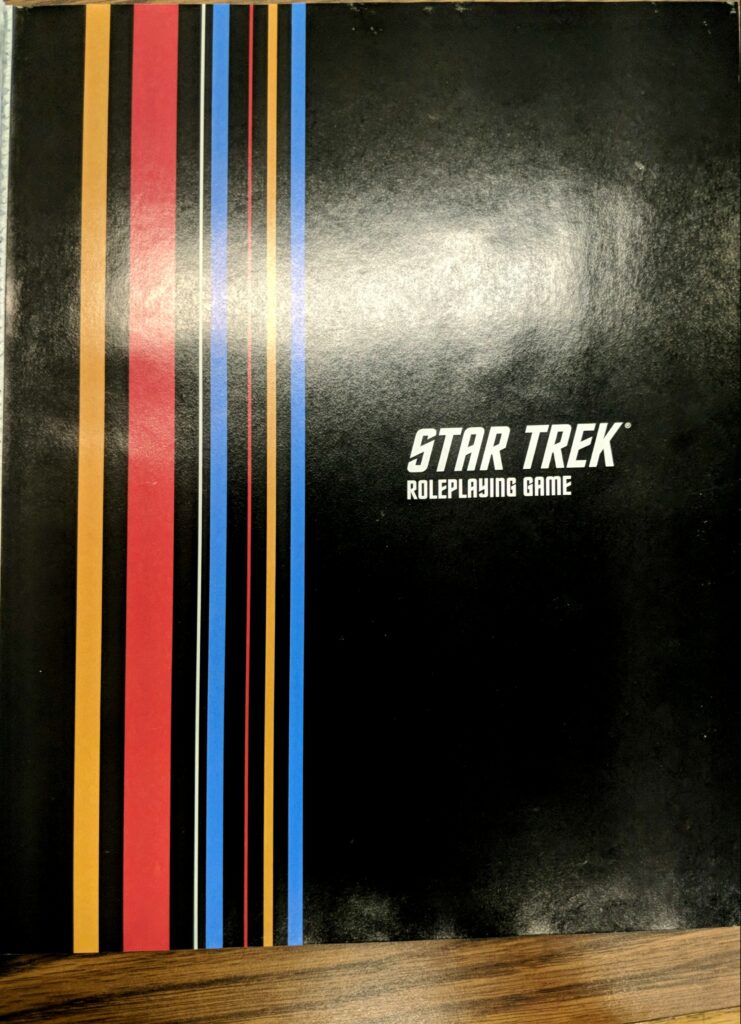

In other games, the role of the game master extends beyond general descriptions and into evoking source material and genre through audio. Star Trek: Roleplaying Game (1999), from Last Unicorn Games, establishes the need for musical props and sonic “recognitional signals” like writing and performing a Star Trek-esque “Captain’s Log” in the style of the television series, or playing Alexander Courage and Gene Rodenberry’s iconic Star Trek theme song to establish mood at the beginning of a session.

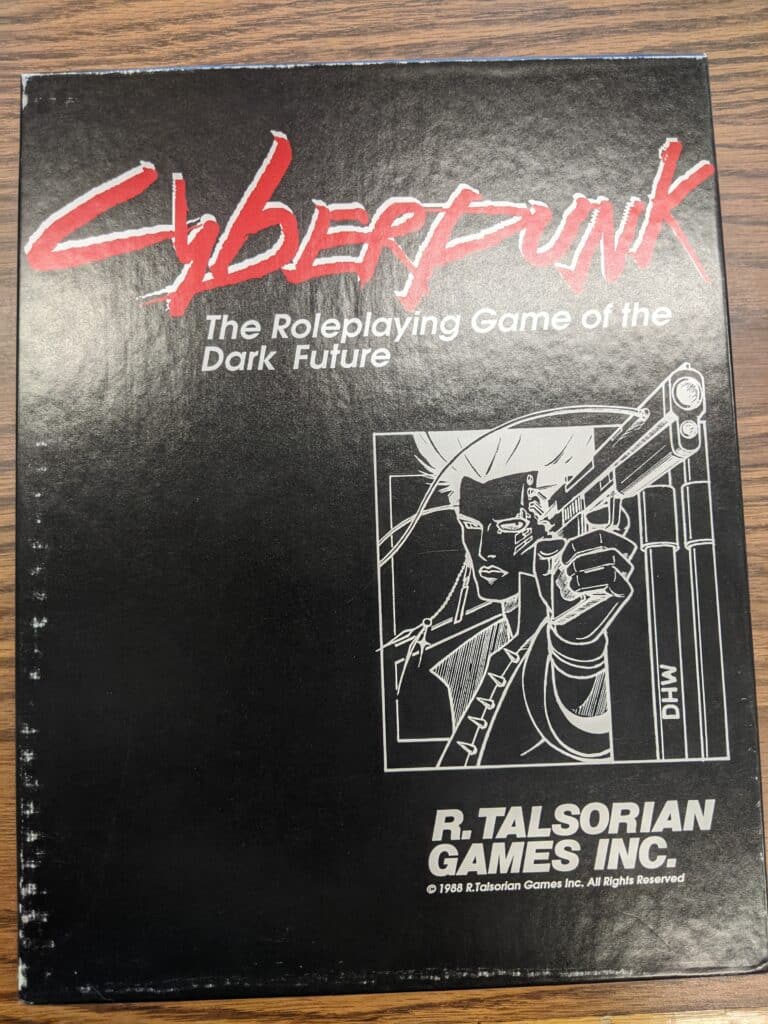

Cyberpunk (1988) from R. Talsorian Games Inc. presses the need for atmosphere to evoke the game’s dark, futuristic setting and suggests an appropriate sonic environment, instructing players to:

Get out your heaviest rock tapes and play them during your run. Encourage your players to wear leather and mirror-shades. Adopt the slang and invent your own… This is the dark future here; and it can’t be accurately portrayed in a brightly lit room with milk and cookies on the table.

Additionally, Cyberpunk doubles down on the sonic atmosphere for its setting, providing the option of playing as a “Rockerboy/girl” who uses music of any genre to make political statements, as well as provide in-narrative music reviews of fictional bands and albums such as Johnny Silverhand’s A Cool Metal Fire.

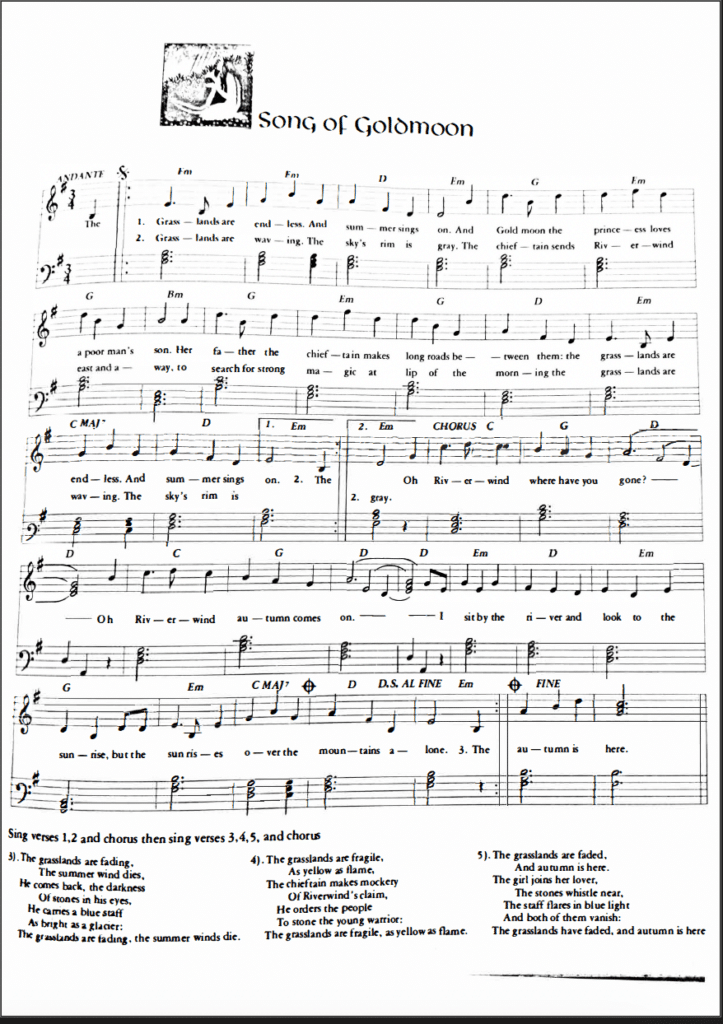

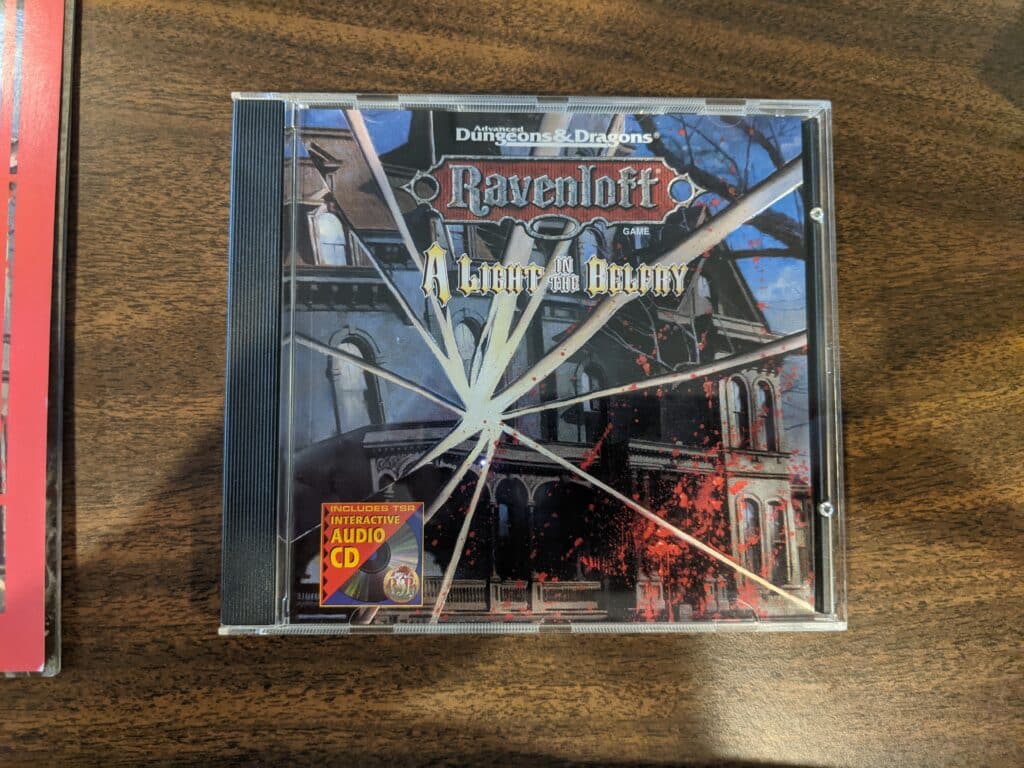

TTRPG companies’ attention to sonic and musical detail also extended into providing musical material as role-playing aids, starting as early as 1984. In an official game adventure for TSR’s Advanced Dungeons & Dragons entitled Dragonlance: Dragons of Despair (1984), the author Tracy Hickman, along with members of the design staff Michael Williams and Carl Smith, composed “Song of Goldmoon,” a song specifically for use in the module. Hickman calls out this piece as vital to the adventure and instructs that one of the players read the lyrics aloud, or, if any players have “natural minstrel abilities,” to sing it with the music provided. TSR’s foray into musical material continued into the 1990s. The Strong houses one of TSRs Advanced Dungeons & Dragons audio adventures that includes a CD for use during play.

Ravenloft: A Light in The Belfry (1995) is a full campaign for Advanced Dungeons & Dragons set in D&D’s horror genre setting, Ravenloft. Along with the text, the adventure includes a CD with 87 different tracks that include narrative performances of the in-game story and atmospheric descriptions, as well as sound effects that enhance a spooky atmosphere. The CD is integral to play as the first 13 tracks tell the story of the adventure’s antagonist, Morgoroth, that players discover as a part of the game. The tracks on the CD are meant to be played as the players explore a haunted house, with each of its rooms having a dedicated narration and musical elements associated with the horror genre, such as eerie strings, bells, and synthesizers.

In addition to the musical and sonic work published by game companies, The Strong houses collections of unpublished materials from various game designers as well as materials created by TTRPG players for personal and public play. In particular, the Play Generated Map and Document Archive papers (PlaGMaDA) contain thousands of player-generated documents including character sheets, maps, GM notes, and homebrew adventures. PlaGMaDa offers insight into a lived TTRPG past and shows how players from various backgrounds interacted with sonic and musical ideas. Within the parts of PlaGMaDA that I was able to look through during my short time in the archives, I found that players experienced and engaged with music in different ways.

Many of these instances consisted of small notes of things that implied the presence of musical objects. In a collection of notes and maps for a game of Chaosium Inc.’s Call of Cthulhu, the game master detailed a short list of things in an apartment: “Liquor, Hi-Fi jazz records, promo glossies, occult books.” Despite the innocuous nature of this note, its inclusion suggests the owner of this apartment listened to “Hi-Fi Jazz,” and this in turn generates assumptions based on what the game master and the players associate with that genre of music.

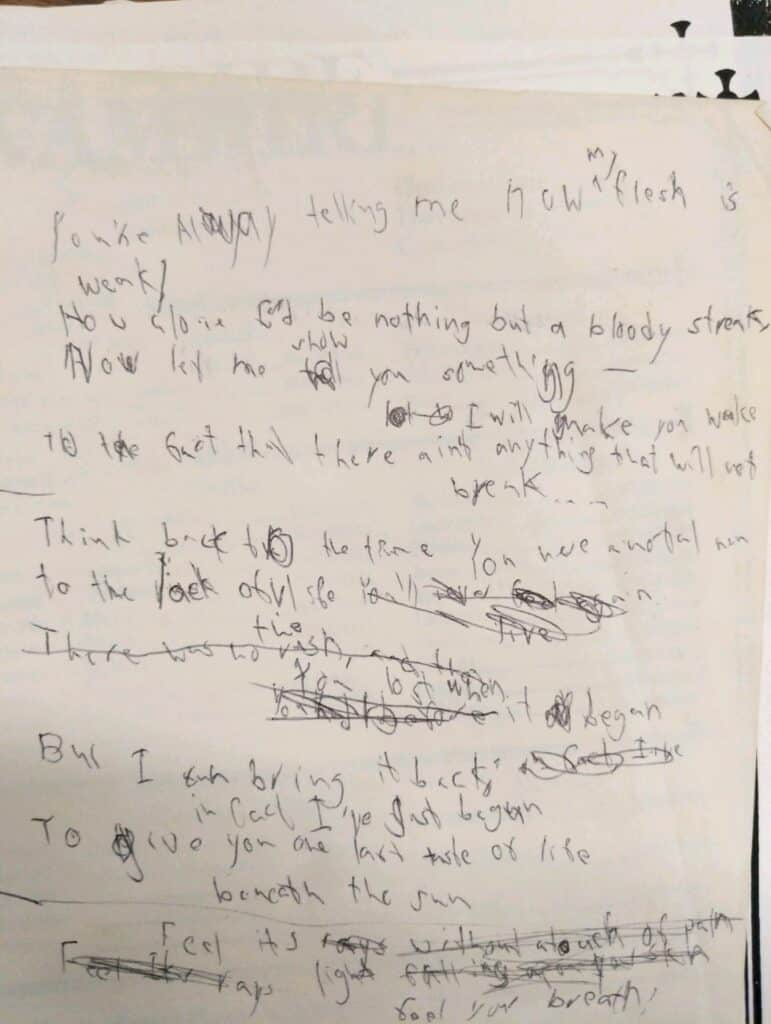

Players also explored the possibilities of music within their games in another collection of character sheets dated between 2004-2007. A player drafted a song for a character they were playing in Mage: The Ascension (White Wolf Publishing, Inc., 1993). Set in the gothic-punk universe of the World of Darkness games, the song features edgy lyrics typical of a punk song.

The document shows how the player engaged with music by writing lyrics themselves, as well as implies that they were thinking critically about their writing. The crossed-out lyrics and rewritten lines imply that the player spent more than a few moments on their writing. In a sticky note attached to these lyrics the donor states: “Draft of a song [player’s name] wrote on as his MagePC [player character] Rain from the 06 game.” There is no record indicating whether this song was ever performed or what it possibly sounded like; however, its presence demonstrates how TTRPGs provide space in which creativity and musical practice can be explored through a play environment.

My time during my fellowship at The Strong has had a profound impact on my research into music and TTRPG communities. Contemporary TTRPG communities often consider the use of sound as a modern phenomenon that align with the resurgence of popularity in the genre since the mid-2010s. However, I hope my research conducted at The Strong will establish that music and sound have long been integral to TTRPGs as a creative practice.

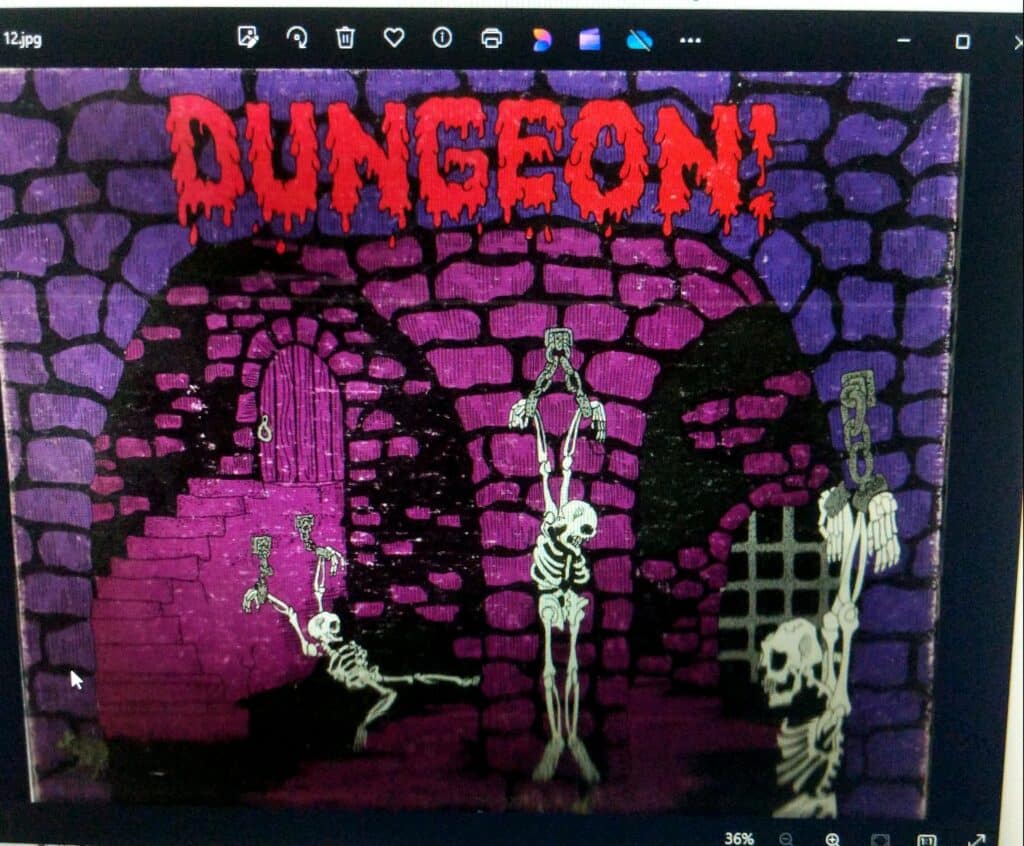

Play, especially play through music and sound, is often ephemeral, as these moments between friends are not (usually) recorded. I was confronted by this ephemerality while examining the William J. Hoyt Dungeon’s & Dragons Collection housed at The Strong. Hoyt was one of the first people to play Dungeons & Dragonsin the 1960s as a part of Dave Arneson’s wargaming group in the Twin Cities area. In a short 15-second sound clip from a slideshow Hoyt put together about the creation of D&D, he shows a copy of the game Dungeon! (TSR, 1975) and reminisced on these decades-ago moments that exist now only in Hoyt’s memory. Like so many gaming groups in today’s world, Hoyt describes these playful moments with fondness, and speaks to the sustained importance of music and sound in TTRPG play:

“This is my first copy of Dungeon!. We played this game over, and over, and just loved this game. We played it, and made up songs, and just had a great time playing this game.”

Written by Andrew Borecky, 2024 Valentine-Cosman Research Fellow