Your hands are shaking as you fumble with the small, plastic pieces, eyes scanning the red board for the hole that matches the shape clutched in your fingers…

The tick-tick-tick of the timer is drowned out by the pounding of your heart in your ears…

You know it’s coming but cannot stop yourself from jumping when the timer stops ticking and BOOM! The game board pops up, launching all the pieces into the air and onto the floor around you.

You breathe a sigh of relief and take a moment to calm yourself down. You can’t stand this game. It’s so nerve-racking!

You sweep the yellow shapes toward you into a pile, push the red gameboard down, and start the timer.

Tick-tick-tick-tick…

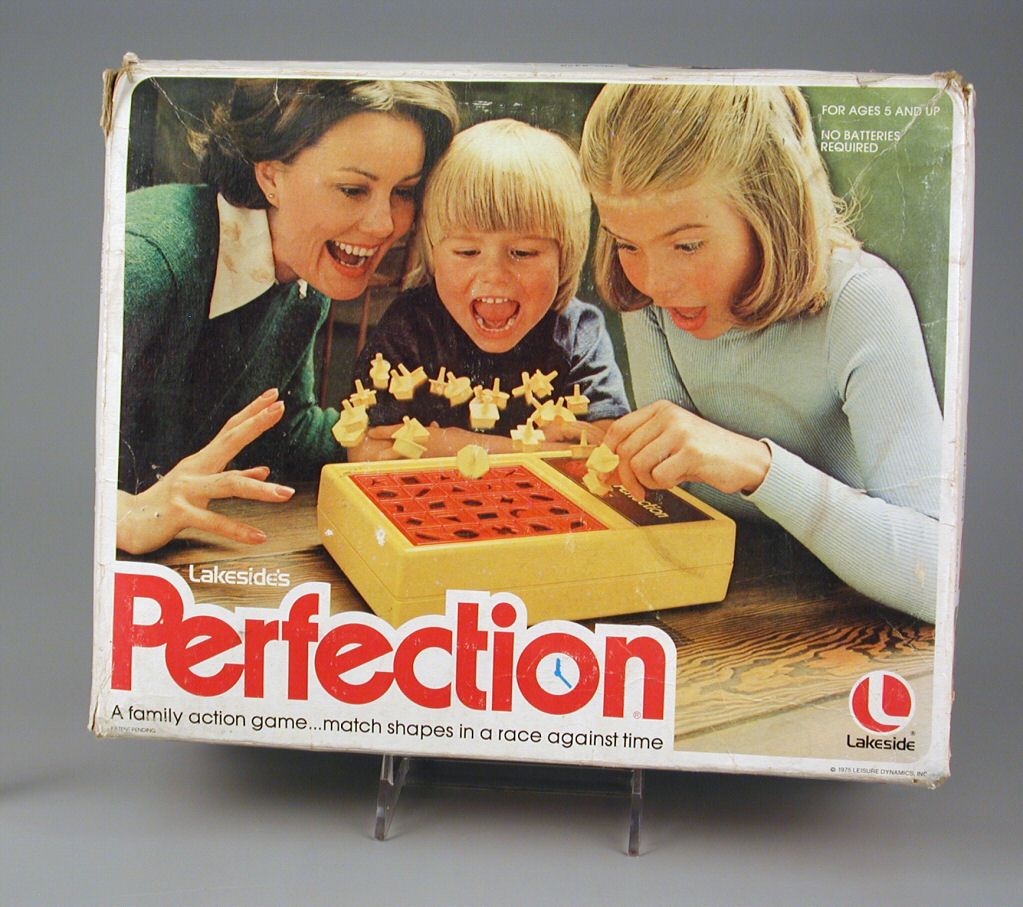

Perfection. A generation feared this game but could not resist its terrifying thrill.

I was afraid of many things as a child—gorillas, dark basements, ordering pizza over the phone, ice skating, quicksand, being hypnotized with a pocket watch in a haunted amusement park, and tire swings, to name a few. The “games” subset of my list of fears included Perfection and a card game called Spit.

Spit is a fast-paced card game where players try to be the first to get rid of all their cards. Some versions of the game have the opposite goal to finish with the most cards. In the variation I played with my cousin during a summer break, when either player has played all the cards in their hand it becomes a game of quick reflexes—the first to slap the smaller pile of cards adds that pile to their hand while the other player must take the larger pile into their hand. Me being an easily startled slow slapper meant that my cousin beat me every single hand. I never won a game against her. Over the course of the summer, however, I went from jumping and shrieking at every slap to enjoying the challenge and the silliness of the game. There was no need to be competitive or self-conscious—the suspense and chaos was the point and the thrill of the game.

From a psychological perspective, the appeal of games like Perfection and Spit makes sense—humans like to be frightened. In his 2018 article for USC News, “Why Do We Like to Be Scared?”, Eric Lindberg explains, “A flood of fear paired with the relief of safety can release naturally occurring opioids like endorphins that signal pleasure, along with a hit of dopamine, a chemical linked to the brain’s reward center.” These endorphins are why people like roller coasters, haunted houses, suspense novels, slasher films, and the new kid on the play block—horror video games.

When my youngest child was seven years old, I walked by his room one day and noticed he was sitting on his bed, head in his hands, tablet at his side, taking deep breaths. I stopped and asked him what was wrong. He said he was playing a game that was scary and that he needed a minute to calm down before playing it again. Mom-mode kicked in and I assured him that he didn’t have to play a game that scared him and demanded to know the name of the game and which sibling was making him play it. He patiently explained to me that the game was called Five Nights at Freddy’s and that no one made him play it. In fact, none of the other kids in the house were even playing this game yet!

Five Nights at Freddy’s was released by Scott Cawthon in 2014 after his previous video game release was criticized for its creepy animatronic-like characters. Cawthon had not intended his characters to be creepy in that game but set out to create intentionally scary characters in his next release. Five Nights at Freddy’s (FNAF to fans of the franchise) is set in a fictional pizza restaurant that has a group of animatronic mascots that sing and perform for children’s parties—a bear, a bunny, a chicken, and a fox. At night this animatronic band comes to life and try to kill you, the hapless security guard. FNAF proved to be wildly popular and has more than a dozen sequels and spin-offs.

My son was among those instant fans of all things FNAF. He wanted to get used to the “jump scares” so he could get better at the game. He liked the thrill, the story, the scramble to close the right door or turn on the light at exactly the right time. He went on to beat the game and to introduce it to his older siblings.

That is the other part of the fear/fun equation: the conquering. To enjoy the game, he needed to face his fears. Similarly, my exposure to Perfection and Spit challenged me through my extra-anxious years by getting me out of my comfort zone.

In “Play as Experience,” appearing in the Fall 2015 issue of the American Journal of Play, play scholar Thomas S. Henricks investigates what he believes is one of the more important aspects of play—the experience it generates in its participants. Henricks writes “we do not play just to experience fear, anger, and other fundamental feelings but to reacquaint ourselves with their challenges and, through this reacquaintance, to rob them of their powers over us.”

Playing games that challenge us can teach us how to better move around in the real world. So don’t let that concept scare you…