It’s 9:43 a.m. on September 19, and you’re eyeing the morning’s deadlines when the usually reserved graphic artist pokes her head into your office and says, “Ye’ll have me that copy before the sun is over the yard-arm, or I’ll have ye walkin’ the plank, ye swab, ye scurvy son of a sea dog.” With a flourish, she whips an X-Acto knife in her teeth. You notice that she’s wearing a tri-cornered felt hat with the Jolly Roger on the brim. “Harrr…” you think; it’s National Talk Like a Pirate Day again…

Dave Barry, a humor columnist, popularized the holiday in 2002 and now it’s officially recognized in three states. All over the country and the world (now that the observation has gone viral), people channel the Anglo-Cornish maritime dialect that came to us via Gilbert and Sullivan’s operetta, The Pirates of Penzance, and especially from the performances of English actor Robert Newton who portrayed the “gentleman of fortune,” Long John Silver, in Disney’s version of Treasure Island. Newton played Blackbeard too, a couple of years later.

The real Blackbeard, Edward Teach, a pirate of the Caribbean if ever there were one, hailed from the seaport Bristol, where English speakers dropped their “h’s” and rolled their “r’s” and dropped the “l’s” at the end of words. They used the infinitive for the verb “to be” as well—as in “he be a right buccaneer.” In an earlier age, Sir Francis Drake, sanctioned as a privateer and knighted by Queen Elizabeth for his exploits against the Spanish, having grown up in extreme southwestern England—a haven for smugglers—spoke this way too. Despite the non-received accent, he became vice admiral of the fleet that scattered and sank the Spanish Armada in 1588. When we talk like pirates, we still talk something like real pirates talked.

Queen Elizabeth wasn’t the first or the last to make a pirate a hero. Understanding why takes a bit of explaining. These were robbers after all, as well as marauders and murderers. Yet historians—usually no suckers for romanticized portraits and by nature keen to tell the awful truth—have often gone easy on pirates. They refer to a “Golden Age of Piracy” roughly from 1650 to 1730 when seagoing bandits sanctioned by official “letters of marque” preyed on the rich Spanish galleons bound for Cadiz laden with precious metal and gems stolen from the Incas or mined in Peru.

Adrian Tinniswood, whose admirable history Pirates of Barbary (2010) I can recommend, notes that historians have held up pirates as “heroic rebels without a cause.” And it’s true. Historians have hailed pirates as proto-democrats, embryonic capitalists, and equalitarians, who lived by racial equality and respected gay rights. One historian I know described pirate society as “idyllic” and called me a killjoy when I insisted that the life of a pirate was likely to be nasty, brutish, and short. In fact, pirates, though thieves, were not anarchists; they really did live by a Pirate Code that insured equity, security, and a measure of gallantry. One surviving such document from the eighteenth century, thought to be representative, prohibited dice games that wagered money; enforced lights out at eight p.m.; provided for equitable distribution of booty (specifically rum, which accounted for all the yo-ho-ing); forbade the divisive act of smuggling a disguised woman on board ship; ensured rest for musicians on the Sabbath; and prescribed death or marooning for desertion in battle.

Kevin Murphy, maritime watercolorist and exhibit designer, now retired from The Strong, spends a fair bit of each year cruising the Caribbean and other pleasant climes with his wife, Lorena. He knows more about naval history than I will ever know about any subject and has this to say about pirates: “Playing pirate, or reading about them or watching them at the movies or even boarding a themed thrill ride in Disneyworld in this rule-bound age, gives us a way to act out fantasies of defiance.”

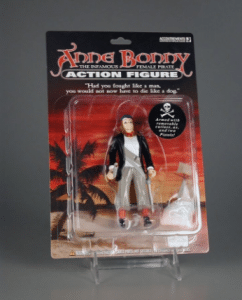

Though when we think of pirates, we think of an all-male society of gleeful anarchists, but a few women became pirates too. Anne Bonny was one. Bonny’s father raised her as a boy called Andy, and she proved to be a match for any pirate. In the early 18th century, Bonny, who talked (and enthusiastically swore) like a pirate (but with the Irish accent of her native coastal town, Cork), joined another, Mary Read, and they conspired to steal the sloop William that lay at anchor in Nassau—a sanctuary at that time otherwise known as the “Pirate Republic.” The two joined the notorious Captain Calico Jack Rackham who they had met in a Bahamas tavern and enjoyed a career with him on the pirate ship Revenge until apprehended by a king’s ship in 1720. Bonny and Read fought bravely, but the rest of the crew, too drunk to resist, surrendered easily. As he stood on the gallows, Rackham is reputed to have denounced his crew: “Had you fought like a man, you would now not have to die like a dog.” And those last words now appear on the “Anne Bonny, The Infamous Female Action-Figure” that The Strong now holds in its collections. The story may have ended happily, though. Bonny, pregnant, “pled her belly” and so escaped execution, perhaps to take up piracy again. Or perhaps, as another version of the tale goes, her estranged father sprung her from prison and married her off to a Virginia gentleman, Joseph Buerliegh, with whom she bore another eight children and lived into her eighties.

Though when we think of pirates, we think of an all-male society of gleeful anarchists, but a few women became pirates too. Anne Bonny was one. Bonny’s father raised her as a boy called Andy, and she proved to be a match for any pirate. In the early 18th century, Bonny, who talked (and enthusiastically swore) like a pirate (but with the Irish accent of her native coastal town, Cork), joined another, Mary Read, and they conspired to steal the sloop William that lay at anchor in Nassau—a sanctuary at that time otherwise known as the “Pirate Republic.” The two joined the notorious Captain Calico Jack Rackham who they had met in a Bahamas tavern and enjoyed a career with him on the pirate ship Revenge until apprehended by a king’s ship in 1720. Bonny and Read fought bravely, but the rest of the crew, too drunk to resist, surrendered easily. As he stood on the gallows, Rackham is reputed to have denounced his crew: “Had you fought like a man, you would now not have to die like a dog.” And those last words now appear on the “Anne Bonny, The Infamous Female Action-Figure” that The Strong now holds in its collections. The story may have ended happily, though. Bonny, pregnant, “pled her belly” and so escaped execution, perhaps to take up piracy again. Or perhaps, as another version of the tale goes, her estranged father sprung her from prison and married her off to a Virginia gentleman, Joseph Buerliegh, with whom she bore another eight children and lived into her eighties.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.