Recently, The Strong acquired a rare and important early printed book illustration. The image came to our attention when Gordon Burghardt used it to illustrate his article, “The Comparative Reach of Play and Brain: Perspective, Evidence, and Implications,” in the Winter 2010 issue of The Strong’s American Journal of Play. As professor of both psychology and ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Tennessee, and author of The Genesis of Animal Play, Burghardt specializes in the study of play behavior in both animals and humans. In his article, he used this 400-year-old illustration to show how locomotor, object, and social play endure as features of childhood.

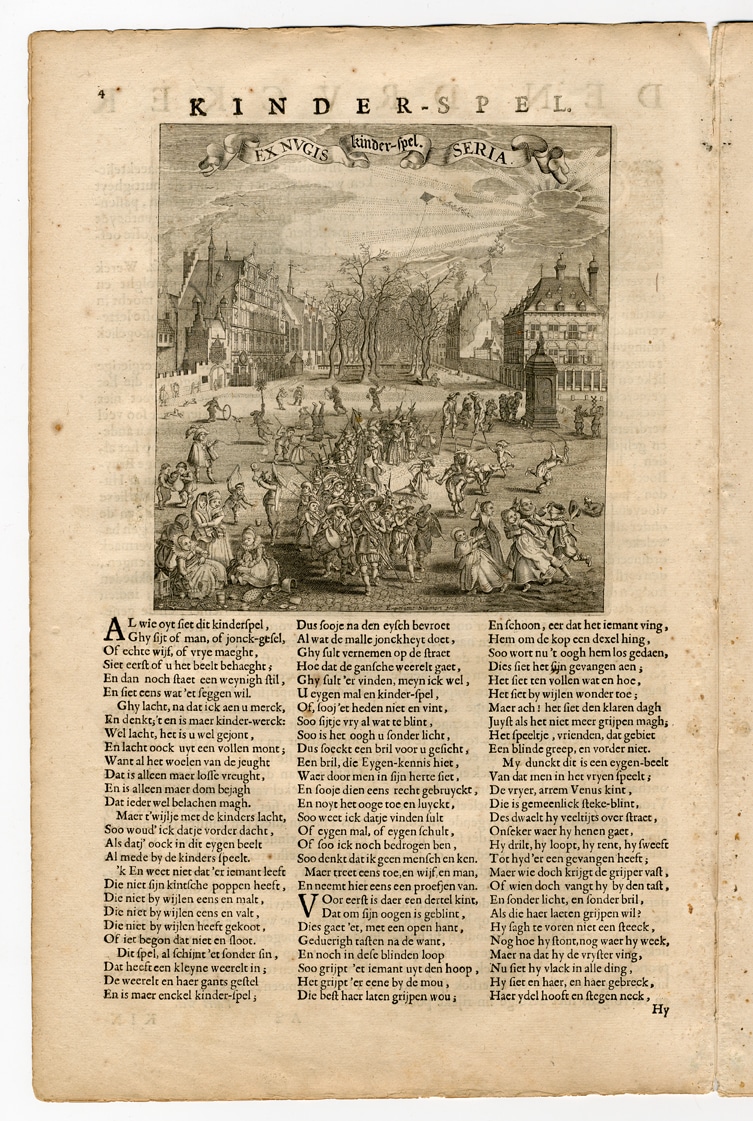

The illustration Kinder-spel or “Children’s play” opens the first chapter in an “emblem book,” Houwelyck, by then-beloved Dutch author Jacob Cats (1577–1660). While the museum’s copy bears a date of 1655, Cats first published it in 1618. The illustration may well be the oldest published and widely circulated image of children at play; and it shows them playing many different ways. Two Flemish painters, Pieter Brueghel and Martin Van Cleve, painted similar scenes of children playing about 100 years earlier, but comparatively few people saw those. Unlike the painters, Jacob Cats published his books, and their popularity lasted through many copies and multiple editions for more than a century.

The illustration Kinder-spel or “Children’s play” opens the first chapter in an “emblem book,” Houwelyck, by then-beloved Dutch author Jacob Cats (1577–1660). While the museum’s copy bears a date of 1655, Cats first published it in 1618. The illustration may well be the oldest published and widely circulated image of children at play; and it shows them playing many different ways. Two Flemish painters, Pieter Brueghel and Martin Van Cleve, painted similar scenes of children playing about 100 years earlier, but comparatively few people saw those. Unlike the painters, Jacob Cats published his books, and their popularity lasted through many copies and multiple editions for more than a century.

Poet, politician, and statesman, Jacob Cats earned fame and respect for his published works in 17th- century Holland. Many Europeans collected these instructional emblem books during the 16th and 17th centuries. Books were expensive and rare, and a moral, instructive volume added grace to any civilized person’s library. While other authors penned religious treatises, Cats himself wrote secular, though moralistic, works and used poetic proverbs to interpret the accompanying illustrations. A center for commerce, shipping, and religious tolerance, as well as for subjects such as art and literature, Holland experienced its only “Golden Age” during this period. In this environment, Jacob Cats stood out, a respected man of letters.

The illustration bears the title of the book’s first chapter on a printed banner. Translated as “Out of Children’s Games—Seriousness,” or more literally “From Trifles Seriousness,” the chapter text and the illustration both demonstrate play’s dualities. Cats deserves note for picturing the everyday life of children and especially children at play. By contrast, our Puritan founders (Cats’s contemporaries across the Atlantic in North America) demonstrated little but suspicion of both children and play. So, in one respect, the illustration demonstrates an enlightened and modern perspective—play is worthy of attention—while in another it harnesses play to outcomes. At the same time, Cats conveyed a contradictory message that play only has value because it allows children to rehearse the roles and activities of their adult lives. This line of thinking isn’t extinct; play is still often thought of as an instrumentality, the “work of children.” Americans now tend to see play as rewarding on its own and a pleasurable part of natural child development, a point of view that separates modern play advocates from Cats and his era.

The illustration bears the title of the book’s first chapter on a printed banner. Translated as “Out of Children’s Games—Seriousness,” or more literally “From Trifles Seriousness,” the chapter text and the illustration both demonstrate play’s dualities. Cats deserves note for picturing the everyday life of children and especially children at play. By contrast, our Puritan founders (Cats’s contemporaries across the Atlantic in North America) demonstrated little but suspicion of both children and play. So, in one respect, the illustration demonstrates an enlightened and modern perspective—play is worthy of attention—while in another it harnesses play to outcomes. At the same time, Cats conveyed a contradictory message that play only has value because it allows children to rehearse the roles and activities of their adult lives. This line of thinking isn’t extinct; play is still often thought of as an instrumentality, the “work of children.” Americans now tend to see play as rewarding on its own and a pleasurable part of natural child development, a point of view that separates modern play advocates from Cats and his era.

The book’s title, Houwelyck, translates literally as “Housework,” and the volume covers the complete phases of a marriage in six chapters, echoing six stages of a maiden’s life. Cats used each type of play—and he fit a multitude of activities into his illustration—as an example and a metaphor, in the accompanying text, for some phase of married life for both men and women. For example, the boy playing Blind Man’s Bluff, wearing a blindfold, warns young men to choose a bride with caution. The man on stilts represents “ego” because he walks above others. And the girls playing with kitchen tools indicate proper preparation for motherhood and household management. Overall, the playful illustration and the text serve to remind young people of both the folly and seriousness of married life. Similar messages occupy self-help texts today.

Scholars disagree about the graphic artist who printed this particular version of Kinder-spel. Some different examples of the illustration are signed by Experience Silliman (1611–1653), a painter and engraver from Amsterdam. But Silliman likely made his version based on a design by Adraen van de Venne (1589–1662) who illustrated most of the earlier Cats works. And, because of the great number of editions over a great many years, stylistic differences in various versions of the image abound. But regardless of the artist who made it, Kinder-spel remains one of the earliest images of children at play, and one of the oldest artifacts in the collections at The Strong.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.