I still remember my first encounter with a dribble cup. It was at my next door neighbor’s house sometime during high school. Mark, who was in my grade, and his dad offered me a drink of water. I suspected nothing, despite their all-too-evident over-eagerness to see me slake my thirst. They handed me an ornate water goblet. To my surprise, when I took a drink, water spilled down my front. Somehow I was oblivious to their broad smiles and took another sip, only to have the same result ensue. My shirt was now soaked, as water had spilled through the glass’s tiny holes. Mark and his dad laughed uproariously.

I still remember my first encounter with a dribble cup. It was at my next door neighbor’s house sometime during high school. Mark, who was in my grade, and his dad offered me a drink of water. I suspected nothing, despite their all-too-evident over-eagerness to see me slake my thirst. They handed me an ornate water goblet. To my surprise, when I took a drink, water spilled down my front. Somehow I was oblivious to their broad smiles and took another sip, only to have the same result ensue. My shirt was now soaked, as water had spilled through the glass’s tiny holes. Mark and his dad laughed uproariously.

Some things never change. One is our all-too-human delight in pranks and pratfalls, especially when they are inflicted on someone else. To catch someone off guard and surprise them is enough to bring a smile immediately to the face of the person playing the prank, though whether or not the person who has been played finds it funny is another matter. Play is often in the eye of the beholder, or the bestower.

I thought of this recently while reading the account of the Duke de Montaigne’s travels from France to Germany, Austria, and Italy in the 1580s. Montaigne was a French nobleman who retired to his villa and wrote a series of delightful meditations on life that established the model for the modern essay. One of my favorite play quotes comes from Montaigne who, in one of his essays, wrote: “Who knows but when I play with my cat but she plays with me.” It’s a wonderfully humble and insightful comment about the possibilities of play in man and beast.

In 1580, Montaigne set off from his villa in France for a trip to Rome. Along the way, he stopped in various towns and recounted the character, mores, and habits of the people who lived there. He had a keen eye for the telling detail, whether it was the cut of clothes or the taste of food. In Augsburg, he noted that innkeepers put linen down on the steps after they had been cleaned to keep them from getting soiled, that they perfumed the bedrooms, and that “few meals pass at which they do not offer you sugar candies and boxes of sweetmeats.” He also recorded an indulgence in jokes.

At the summer palace of one of the Fuggers, the prosperous bankers who brought Augsburg its great wealth, Montaigne recorded an intricate system of pipes installed for the purpose of pranks. Between two fish ponds were laid wooden planks for guests to walk on but which also cleverly hid a series of brass water jets. Montaigne wrote:

“While the ladies are busy watching the fish play, you have only to release some spring: immediately all these jets spurt out thin, hard streams of water to the height of a man’s head, and fill the petticoats and thighs of the ladies with this coolness.”

Elsewhere, he noted, while you might be looking at an amusingly constructed fountain, someone can “open the passage to little imperceptible tubes, which from a hundred places cast water into your face in tiny spurts; and in that place is this Latin sentence: You were looking for trifling amusements; there they are; enjoy them.”

Taking pleasure in trifling amusements is part of being human, what brings zest to life, and so it is not surprising that such silliness appears again and again throughout time. Some three centuries after Montaigne wrote about these trick fountains of Augsburg, the proprietors of Steeplechase, one of the most popular attractions in the New York seaside resort of Coney Island, introduced the Blowhole Theater.

The Blowhole Theater provided the same amusement to American city dwellers of the Gilded Age that the trick fountains had given the German burghers of 16th-century Augsburg. After fairgoers had ridden down the Steeplechase ride, they had to exit through a bright stage patrolled by a dwarf and a clown who delighted in shocking couples, quite literally, with an electric cattle prod, usually applied to the derriere of young gentlemen. Women who tried to avoid these lords of mischief found that their skirts were blown unceremoniously upward by great gusts of air from hidden blowholes. When they finally exited the stage, red-faced and (hopefully) laughing, these victims of the joke grabbed a seat in the audience and gleefully watched others suffer the same fate. It was one of Coney Island’s longest-running and most popular amusements. Sour-faced spoilsports were reprimanded with a sign that said, “Don’t be a Gloomster, be a Steeplechaser.”

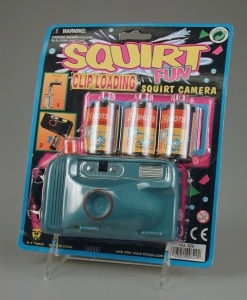

Today, while we might frown on some of these specific stunts and trick theaters, we still haven’t lost our zest for a good practical joke, as items like keyboard ketchup gags and trick cameras in The Strong’s collection attest. Television shows such as Candid Camera, Just for Laughs, and Practical Joker give us a good chuckle at seeing other people made fools of. Sometimes these tricks can be too meanspirited, but most of the time we benefit from having our pride punctured and our egos deflated with a good joke. It’s usually a good idea not to take ourselves too seriously, and a dribble cup can be a wonderful mechanism for reminding us of that fact.

Today, while we might frown on some of these specific stunts and trick theaters, we still haven’t lost our zest for a good practical joke, as items like keyboard ketchup gags and trick cameras in The Strong’s collection attest. Television shows such as Candid Camera, Just for Laughs, and Practical Joker give us a good chuckle at seeing other people made fools of. Sometimes these tricks can be too meanspirited, but most of the time we benefit from having our pride punctured and our egos deflated with a good joke. It’s usually a good idea not to take ourselves too seriously, and a dribble cup can be a wonderful mechanism for reminding us of that fact.

By Jon-Paul Dyson, Director, International Center for the History of Electronic Games and Vice President for Exhibits

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.