By: Hana Hanifah, 2025 Valentine-Cosman Research Fellow

In recent years, the momentum for accessibility in games has gained significant traction. Many custom configurations, such as captions, remappable controls, and adaptable hardware, are becoming the norm as more people, especially those with disabilities, play and engage in games. The Xbox Adaptive Controller and the PS5’s Access Controller have been rightly praised and documented in the mainstream media. However, several decades before they emerged, there was an innovation that quietly went to the grave. In 1989, Nintendo of America released the Handsfree Controller, specifically designed for players with physical disabilities; few today even know it was ever made. As part of my research on accessibility, I took a trip to The Strong National Museum of Play in Rochester, New York, one of the few places this rare artifact can still be found.

In the history of gaming, accessibility innovation has never come from corporations; it has come from gamers with disabilities. Before “inclusivity” became a corporate term, disabled gamers created their own controllers, modified existing ones with innovative approaches, and shared DIY process documentation on forums and newsletters. The most notable early examples are attributed to Ken Yankelevitz and David Luntz, who in the mid-1980s were the co-creators of some of the first commercially accessible adaptive gaming controllers available to the public. Both men, working independently from one another, constructed options for limited mobility players to access commercial gaming systems using modified interfaces and alternative input.

Historically, the early accessibility developments documented in popular media appeared only when the projects were described in the context of a therapeutic tool. In the rare instances where gaming and disability intersected in a mainstream sense, articles in mainstream publications emphasized the medical benefits of the leisure medium, specifically benefits seen in rehabilitation programs used in occupational therapy, as opposed to focusing on play as a cultural process and fundamental right. Yet, the collaboration and innovation were beginning to build. Then in 1987, the momentum shifted to one of the largest corporate entities in gaming.

A Mother’s Letter and Nintendo’s Reply

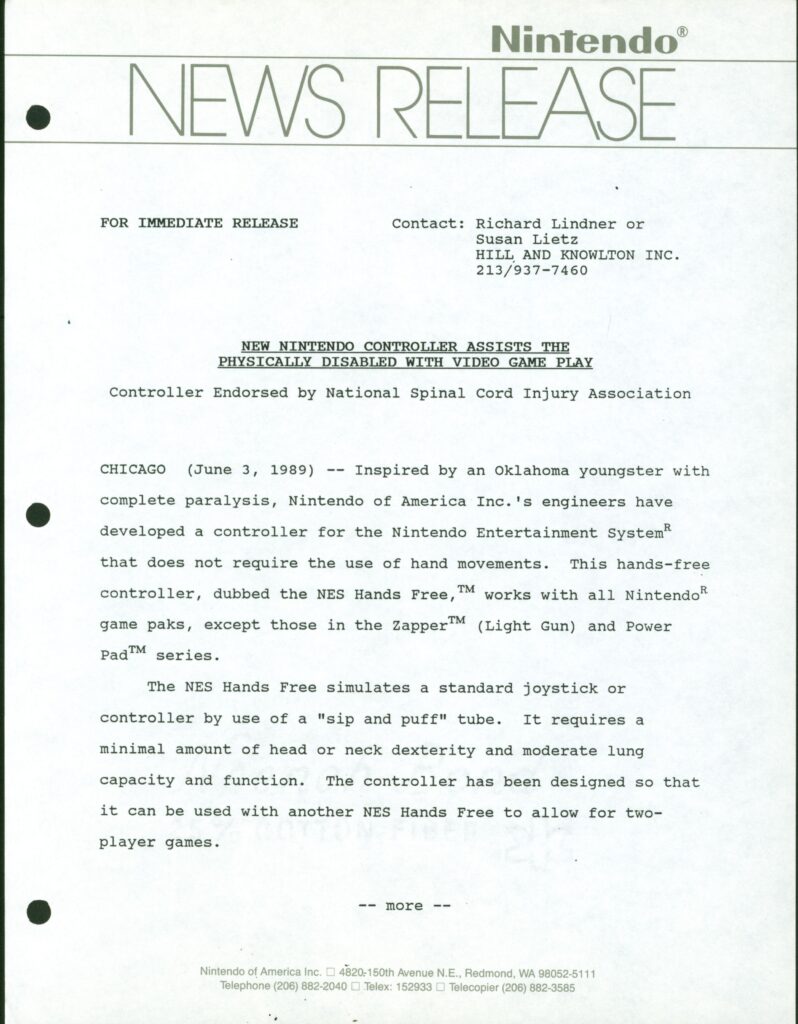

The start of Nintendo’s Handsfree Controller can be traced back to a letter, which was neither an ordinary letter nor an inconsequential request. A mother from Oklahoma wrote to Nintendo of America to inquire if there was any possible way her 12-year-old disabled child might play video games like every other child. Instead of disregarding her request or responding with a form letter, Nintendo decided to engage with the request. They partnered with Seattle Children’s Hospital and received support from the National Spinal Cord Injury Association to develop an adaptive controller that could be operated hands-free.

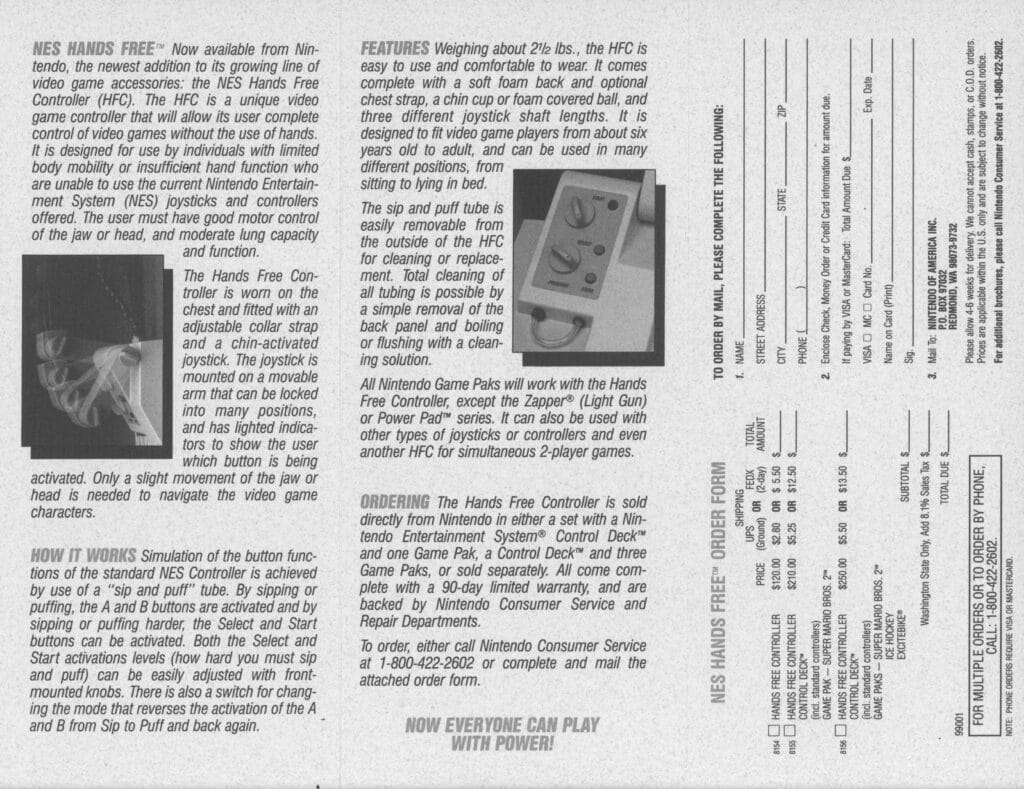

It took nearly two years to develop the Handsfree Controller, with engineers and medical professionals involved, but largely motivated by self-advocates, as they referred to them. The technology included several key features. Most notably, it was claimed to be advanced in supporting a gamer without requiring physical use of their hands. The controller was operated with a chin joystick for directional movement. It also included sip-and-puff inputs, which effectively simulated a button press. Finally, it had bars that were wrapped around the player’s shoulders, which held the controller securely to the user’s body.

The Handsfree Controller was released in mid-1989 at a price of $120, which was almost twice the cost of the NES console ($79.99). Unlike any other Nintendo peripherals, though, you could not go into a store and buy the controller. Players would have to call Nintendo’s customer service to order one directly from the company.

A June 3, 1989, press release issued by Nintendo excitedly proclaimed: “New Nintendo Controller Assists the Physically Disabled with Video Game Play.” The press release detailed the controller’s inventive function, its collaborative design process, and its direct ordering procedure. The image illustrates the product derived from a community process, highlighting that the controller was officially endorsed by the National Spinal Cord Injury Association, and that it could be ordered directly from Nintendo’s customer service department.

However, other than that early press release and a brief mention in Nintendo’s 1989 product fact sheet, I found almost no contemporary media coverage. The controller was completely absent from game magazines, retailer ads, and store circulars of that time. Even Nintendo’s own sensibilities surrounding this product (most notably with their “World of Nintendo” ads) featured fairly comprehensive pictures of controller accessories, but not the Handsfree Controller. This absence of archival coverage says a lot about how the gaming industry and media conceived of accessibility in the late 1980s.

A Market Not Ready for Inclusion

The $120 price tag for the Handsfree Controller was steep from the get-go, especially when a complete system costs less. The direct-only distribution mechanism had real implications for consumer demand, as there was no retail advertising, no word-of-mouth interaction, and ultimately no way for a potential customer to “test drive” the device. Nintendo did not allocate any marketing budget for promoting the Handsfree Controller with traditional mainstream advertising. And there is no evidence that they provided hands-on demo units to mainstream gaming magazines or disability-support organizations.

Perhaps the biggest problem was that no NES games took advantage of the Handsfree Controller. In other words, there were no NES games developed specifically for the Handsfree Controller. Unlike current accessibility initiatives that involve hardware designers and software designers working almost concurrently, the Handsfree Controller was exclusively intended to function with the existing NES game titles that had never integrated accessibility into their development process, such as considering alternative means of handling and inputting motion in their games.

All of this occurred within a cultural milieu that also worked against the success of the device. In 1989, disability was poorly represented in consumer technologies in any form, and the world of video gaming had built-in assumptions about its “ordinary” customers that rarely included players with disabilities.

A Missed Opportunity, A Forgotten Legacy

While nowadays, modern accessibility initiatives have companies creating entire systems grounded in principles of inclusive design, Nintendo of America never released another adaptive controller, and they never expanded their accessibility efforts beyond the original Handsfree Controller. The Handsfree Controller was a standalone product and, as an experiment, there was nothing to build on or improve. There was no indication that Nintendo of Japan supported, or even acknowledged the project, which indicates to me that it was likely solely based on the American division’s assessment of the original mother’s letter.

Lack of continuity represents a tremendous loss for us all. The device demonstrated significant technical competence, indicating that the Nintendo engineers understood the fundamental issues related to creating acceptable gaming hardware that supports people with disabilities. The endorsement of the controller by organizations for and of people with disabilities indicated genuine community support. The co-design process with Seattle Children’s Hospital and the National Spinal Cord Injury Association also created a precedent and principle of co-designing accessibility efforts with the communities served, rather than being well-meaning engineers developing items themselves without input from the communities they intended to help. Despite this, the project ultimately failed due to the lack of institutional memory and corporate commitment to accessibility.

However, we should not lose sight of the original concepts and the original designers who enabled this kind of modern progress. The Nintendo Handsfree Controller was the first important—albeit commercially failed—step from a giant corporation that was ultimately ahead of its time. It existed, it worked, and for the very few players who had one, it opened up new experiences in digital play.

The Nintendo Handsfree Controller didn’t transform the world of gaming, but it made a small effort to be more inviting. It gave disabled gamers a rare moment of visibility from a major corporation and laid one more small piece of a gigantic and unfinished set of stones on a path toward truly inclusive gaming.

This little piece of forgotten history raises important questions that are relevant today. What evidence of past accessibility innovations exist in corporate archives? What has disappeared from corporate histories because the clues are buried in internal memos and product catalogs? What would the gaming landscape look like if early attempts such as the Handsfree Controller had been appropriately backed and resourced for development? Most importantly, what can we learn from both the successes and failures of these early endeavors in a future where the gaming industry serves all players?

These questions matter because gaming accessibility isn’t simply about hardware or software. It is about who the participants are for one of the most important cultural and creative media we have today. The Nintendo Handsfree Controller reminds us that this has been a long conversation (longer than most people would know), and that progress means building on and advancing from the accomplishments of the people ahead of you.

This research was conducted at The Strong National Museum of Play in Rochester, New York, with special thanks to their archives and collections staff for preserving these important artifacts of gaming history.