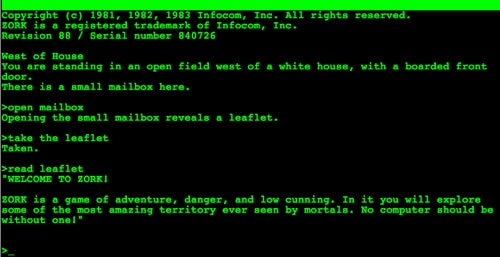

“You are in an open field west of a big white house with a boarded front door.” “There is a small mailbox here.”

These words introduced me to computer games, though I didn’t actually read the words on a computer screen—I read them in stacks of perforated, green-and-white-striped printouts that my older brother, Chris, brought home from school. The stacks of printouts came from an amazing game he and his friends had discovered on the high school’s computer system (a DEC PDP-11) and played on a teletype terminal.

The game invited the player to guide a character through a vast underground realm by typing commands such as “GO WEST,” “LIGHT LAMP,” and “KILL TROLL.” Together my brother and I reviewed where he’d been, drew maps to figure out where to explore next, and brainstormed how to solve the game’s puzzles. How could he open the jeweled egg he found in a tree? What combination of buttons operated Flood Control Dam #3? How could he keep the thief from stealing his stuff? To kids like me, who played Dungeons and Dragons and read Choose Your Own Adventure books, this new game offered endless possibilities, even if I could only experience it vicariously through my brother’s play.

The game was Dungeon, a renamed version of the classic mainframe game Zork. Gamers of a certain age will recognize it immediately as a text-based adventure. Will Crowther created the first text-based adventure when he programmed Colossal Cave Adventure in 1976. Don Woods modified and expanded Crowther’s program in 1977, and the program, known usually as Adventure, spread to mainframe computer systems nationwide. It inspired numerous programmers to devise their own text-based adventures, including a group of MIT students who developed Zork.

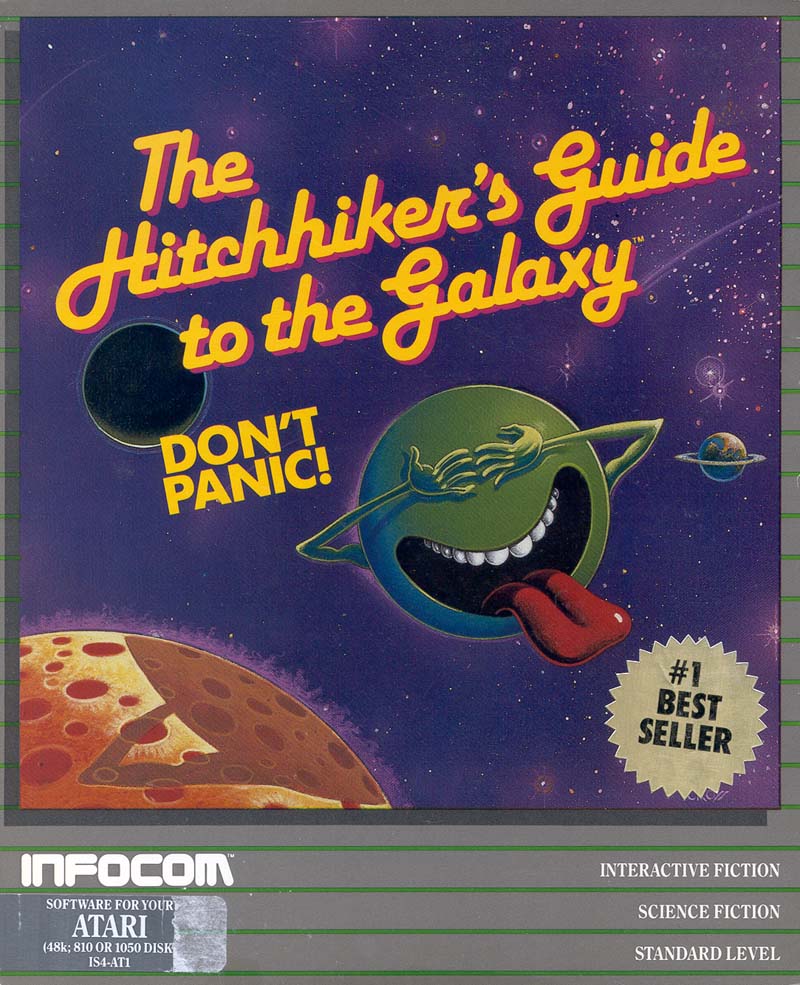

In 1979, several of Zork’s creators helped found a software company called Infocom. Infocom divided the mainframe version of Zork into several parts, elaborated them, and issued them as Zork I, Zork II, and Zork III. Infocom published numerous other titles as well, including Starcross (1982), Deadline (1982), and Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (1984). Infocom’s text-based adventures featured a spare writing style, a wry sensibility, plenty of mind-challenging puzzles, and some of the best packaging in the history of computer games.

Text-based adventures thrived in the early 1980s until role-playing computer games with graphical interfaces, such as Ultima and Might and Magic, eclipsed them in popularity. It would be a mistake, however, to think of games like Zork as merely the earliest ancestors of today’s high-powered fantasy games like World of Warcraft and Fable. While limiting the player’s actual options to a manageable set of recognized commands, those pioneering text-based interfaces, could, in the hands of a good programmer and writer, provide the illusion of a world of infinite possibilities. Zork and other games of that genre were smart, funny, and fired the imagination. Most of all, they elevated the role of puzzle-solving to a central feature of computer games, though too few games today (Professor Layton and the Curious Village stands out as one) match the complexity of the puzzles in these text-based adventures.

Few people play text-based adventures today, but a number of enterprising individuals are exploring their history and significance. Nick Montfort has published a history of the genre: Twisty Little Passages. Dennis Jerz recently published a fascinating article that rediscovers not only the original source code for Colossal Cave but also the original cave in Kentucky that inspired the game. And recently I talked with Jason Scott who is finishing up a documentary about text-based adventures titled, Get Lamp. If you’re interested in learning more about Jason’s efforts you can go here or watch this trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JzOPVe7Usms&fmt=18.

I can’t wait to watch Jason’s documentary to relive some of my own memories. When I reached eighth grade, I got access to the school’s PDP-11 and no longer had to “play” vicariously through my brother’s printouts. I could play Dungeon on my own. Playing opportunities were scarce at school, however, so I never completed Dungeon. Fortunately my parents purchased a home computer bundled with Adventure, and my brother and I spent weeks finishing it. I even got a copy of Zork I and Zork II. I finished Zork I but not Zork II.

By Jon-Paul Dyson, Director, International Center for the History of Electronic Games and Vice President for Exhibits