As a kid, I loved playing hide-and-seek. My favorite variation was a team-based game in which a dozen of us hid and chased each other through the streets and backyards of my densely packed neighborhood. Because we all knew the best places to hide, no one could stay in the same spot for more than a few minutes. In such an environment, the game hinged on making difficult choices such as when to sacrifice one of our slower teammates for the good of the group or when to expose oneself to potential capture in order to allow a teammate to escape the enemy. This game taught me about strategic thinking and how to make quick decisions under pressure. It also encouraged me to consider my own set of moral principles. For instance, would I sacrifice a friend to save myself in the world outside our game?

As a kid, I loved playing hide-and-seek. My favorite variation was a team-based game in which a dozen of us hid and chased each other through the streets and backyards of my densely packed neighborhood. Because we all knew the best places to hide, no one could stay in the same spot for more than a few minutes. In such an environment, the game hinged on making difficult choices such as when to sacrifice one of our slower teammates for the good of the group or when to expose oneself to potential capture in order to allow a teammate to escape the enemy. This game taught me about strategic thinking and how to make quick decisions under pressure. It also encouraged me to consider my own set of moral principles. For instance, would I sacrifice a friend to save myself in the world outside our game?

In game designer and scholar Jose’ P. Zagal’s essay on the game Heavy Rain (2010), he argues, “For many players, games provide a context in which they can wrestle with moral dilemmas, enact scenarios they could potentially experience in real life but would rather not do, and perhaps also learn something about themselves and their personal values.” Much like Heavy Rain, Telltale Games’ recent episodic zombie adventure video game The Walking Dead (season one: 2012; season two: 2013-2014) encourages players to experiment with ethically-complex choices and to confront their own values in a virtual space. The game acts as a kind of laboratory that centers on experimenting with challenging choices few of us would want to face in the real world. Warning, spoilers ahead!

In The Walking Dead game players inhabit the world of author Robert Kirkman’s The Walking Dead comic books (2003-present) and cable station AMC’s The Walking Dead (2010-present) television show. In this world, the rule of law has disappeared and the ties that bound nations, communities, and families together have broken apart in the wake of a zombie apocalypse. Players encounter the living and undead through the eyes of Lee Everett, a former University of Georgia history professor convicted of murdering his wife’s lover. Along the way, he meets Clementine, a precocious eight-year-old girl whose safety and survival become Lee’s purpose for living and chance at redemption.

From the game’s very first screen, which states, “This game series adapts to the choices you make. The story is tailored to how you play,” it’s clear players will face important decisions through their actions and through what they choose to say (using dialog or conversation trees) when talking to other characters. These painful and emotional choices are often time sensitive, giving players only a few seconds to process and respond to what’s happening. For example, in the first episode, the player (acting for Lee) must choose between trying to save Shawn, a kind young man who invited Lee and Clementine back to the safety of his farm, and Duck, a fast-talking 10-year-old boy, from flesh-eating zombies. After I’d saved Duck the first time I played, I wondered what happens if you try to save Shawn. In subsequent plays my choice affected how Shawn’s and Duck’s fathers viewed Lee, but my experiment showed that someone (Lee or Duck’s father) always saved Duck and Shawn always died.

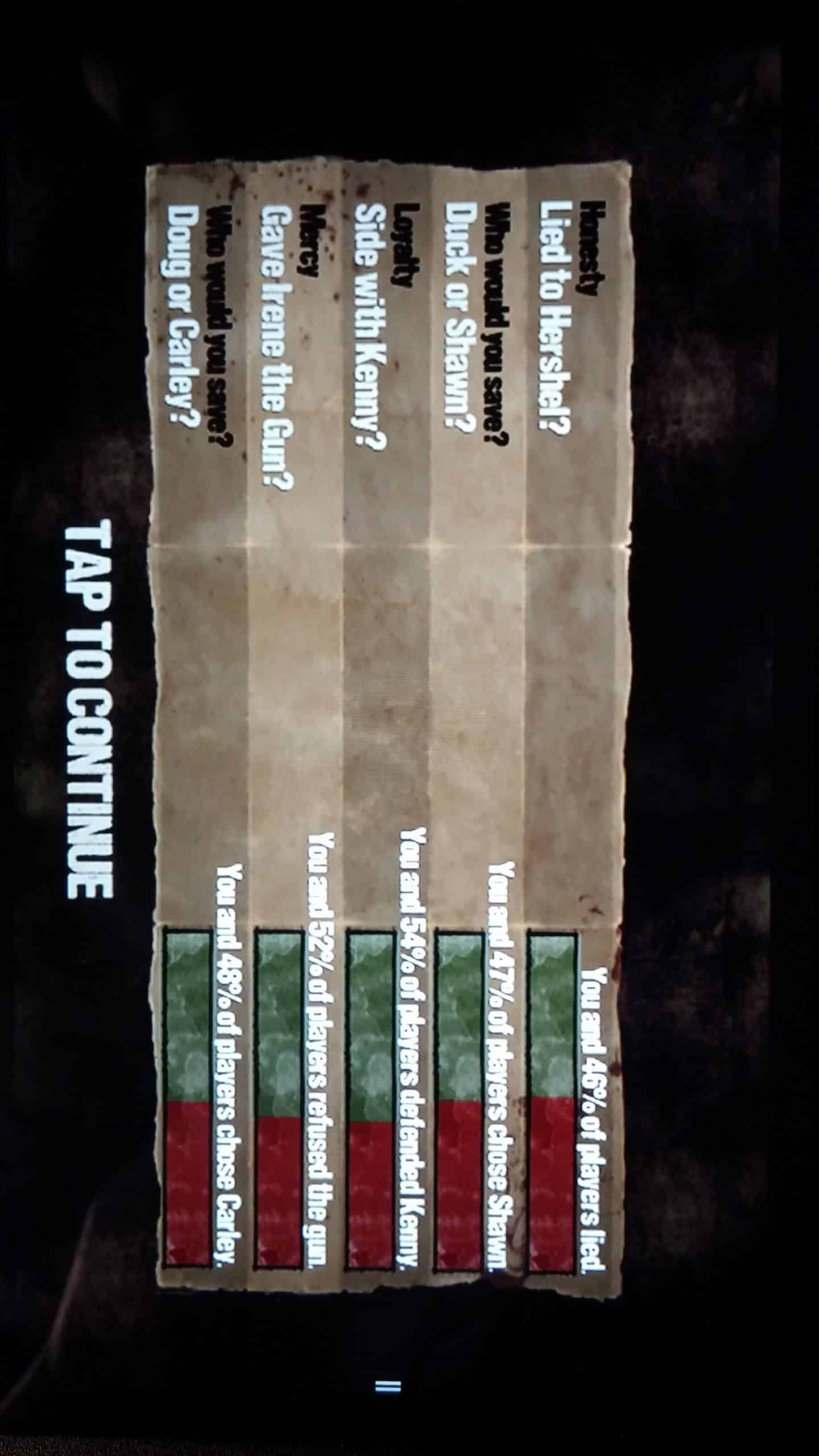

Game scenarios like this one allow players to experiment with their choices, but The Walking Dead also provides players with an opportunity to think more deeply about those choices. At the conclusion of each episode the game displays an analysis that shows what percentage of people made the same decisions as you. In this way, the game isn’t about scoring points, building a character, or even surviving (you can just start again from where you died). It’s ultimately about wrestling with the choices we make and puzzling over why we made those decisions. When only a third of players made the same choice as you, it’s difficult not to ask yourself: Why did I do that?

I suspect that question has dogged many players who think the best games teach us something about ourselves. Hopefully, we’re not afraid of what we find out.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.