Born in 1895, Bertha (Beatrice) Alexander Behrman grew up living above her stepfather’s doll hospital at 405 Grand Street on New York’s Lower East Side. Dolls at that time were made of china and broke easily, so her family kept busy repairing dolls for wealthy clients. Beatrice worked in the shop and, at the age of 11, realized that she wanted to live like their customers. Reflecting later on that determination, she noted, “I wanted to have a carriage and a hat with ostrich feathers.” Beatrice also had the opportunity to go to school, a rarity for many girls in the neighborhood, and she graduated valedictorian from Washington Irving School.

Born in 1895, Bertha (Beatrice) Alexander Behrman grew up living above her stepfather’s doll hospital at 405 Grand Street on New York’s Lower East Side. Dolls at that time were made of china and broke easily, so her family kept busy repairing dolls for wealthy clients. Beatrice worked in the shop and, at the age of 11, realized that she wanted to live like their customers. Reflecting later on that determination, she noted, “I wanted to have a carriage and a hat with ostrich feathers.” Beatrice also had the opportunity to go to school, a rarity for many girls in the neighborhood, and she graduated valedictorian from Washington Irving School.

After completing school, Beatrice married Phillip Behrman, an employee in the personnel department of a hat factory. Beatrice decided to take an accounting course and became a bookkeeper for Irving Hat Stores. In 1915, she and Phillip had a daughter, living comfortably until World War I. Embargoes on goods from Germany threatened the sustainability of her parents’ doll hospital as much of their inventory came from overseas. Beatrice encouraged her family to create cost-effective cloth dolls in the likeness of Red Cross nurses. Not only were these dolls patriotic, but the new material would encourage hands-on play. Her plan spared the family shop.

In 1923, Beatrice founded a doll company. She hired her sisters and a few neighbors to sew. She also took out a $1,600 loan—it was rare for lenders to support women as they considered them poor credit risks. Beatrice was confident, strong-willed, and meticulous. She commanded respect, but also knew how to pull at people’s heartstrings with techniques like bringing her daughter along to meet with vendors and bankers. But sentimentality didn’t rule the day: it was rumored that if Phillip didn’t join the business, she threatened to divorce him. She later recalled, “It seemed to me I can always get another man.”

By this time, Beatrice had assumed the name of Madame Alexander. She was a pioneer in the industry—she popularized sleep eyes (the kind that close when a doll is laid down), rooted hair, and created a variety of sculpts to make her dolls more expressive than her competitors’ products. Madame often frequented the New York Public Library to research costumes for her international doll series and dolls modeled after characters in classic literature such as Gone with the Wind and Alice in Wonderland. In 1942, she released Jeannie, one of the first walking dolls, and a few years later, she created the first plastic face mold.

By this time, Beatrice had assumed the name of Madame Alexander. She was a pioneer in the industry—she popularized sleep eyes (the kind that close when a doll is laid down), rooted hair, and created a variety of sculpts to make her dolls more expressive than her competitors’ products. Madame often frequented the New York Public Library to research costumes for her international doll series and dolls modeled after characters in classic literature such as Gone with the Wind and Alice in Wonderland. In 1942, she released Jeannie, one of the first walking dolls, and a few years later, she created the first plastic face mold.

One of Madame Alexander’s grandest accomplishments occurred in the early 1950s when Abraham & Straus department store commissioned her company to produce dolls representing the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. The 36-doll set included the queen, maids of honor, archbishops, choir boys, royal relatives, and honor guards dressed in great detail, right down to their undergarments from the same mill that manufactured the real coronation wardrobe. CBS even used the dolls to recreate the coronation on television.

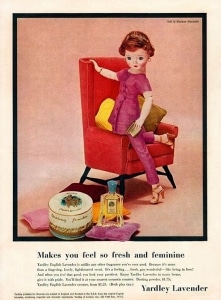

A few years later, Madame Alexander released the first American fashion doll. Cissy had a sculpted bust line and a sophisticated wardrobe—chiffon and satin evening gowns, cotton dresses, and bouffant slips trimmed with lace. Before Cissy, girls were encouraged to nurture their dolls or to think of their dolls as playmates. Cissy represented the start of a more modern America and new roles for women. Yardley Soap even put Cissy in their advertisements to refresh the brand, touting that their soap’s fragrance “makes you feel fresh, gay, wonderful—like being in love.” Some people balked at this new doll and critics today consider Cissy the doll that taught girls appearance and sexuality were the highest priorities for a woman.

Madame Alexander believed that playing with dolls encouraged empathy and kindness. She also aspired to make a space for women in the toy industry. She wanted her women employees to be self-sufficient, even bringing them to Margaret Sanger’s clinic for checkups and birth control. Her secretary said that “Madame Alexander was the original feminist. She was doing a man’s job when the world was not always accepting or approving of an independent woman.” And for that, Madame Alexander, I celebrate you during Women’s History Month.