I was born into a game-playing family. While we spent plenty of evenings watching television, to truly socialize with family members, we turned to tabletop games. Whether our choice was a card game, a board game, or something in the broader games category—Boggle, Stadium Checkers, or Cootie, as examples—games made a favorite way to be entertained and engage with one another.

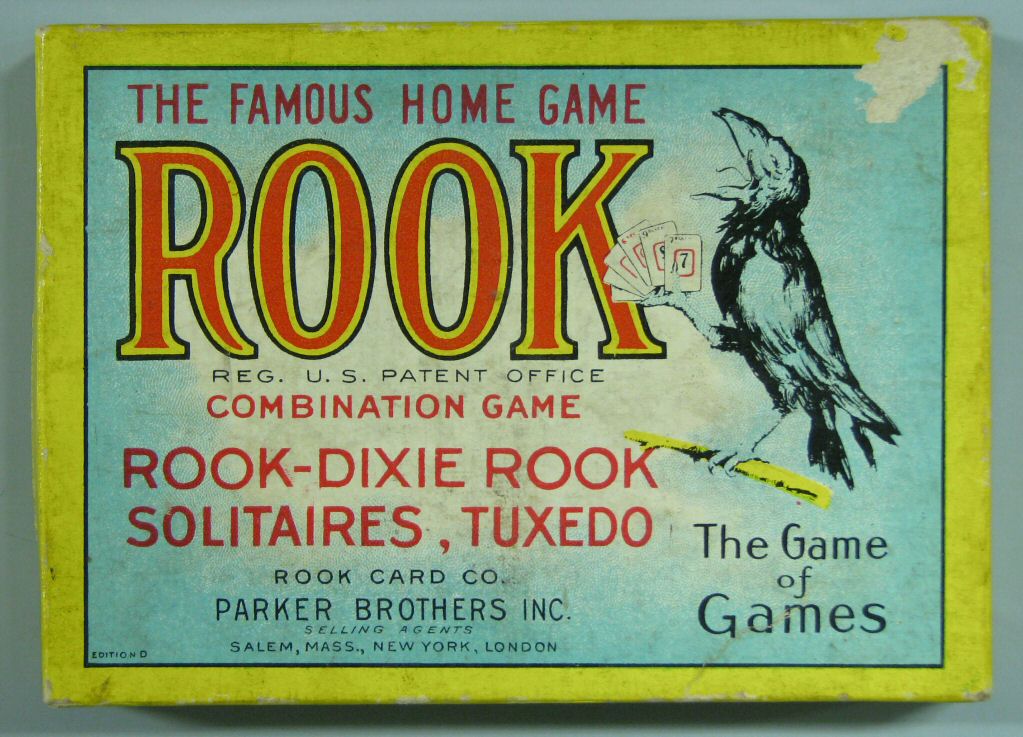

Whether it was genetic or environmental, playing games went beyond my parents to their parents as well. (I never thought to inquire about my great-grandparents’ tastes in play.) My grandparents on both sides of the family loved playing games and were almost always eager to shuffle the cards and let the friendly competition begin. My maternal grandmother’s Methodist upbringing meant that the selection of games at her house included Rook, a 1906 product from Parker Brothers. For certain folks with a conservative religious bent, a standard 52-card deck of playing cards wasn’t an inexpensive source of fun. Those cards were considered “the Devil’s pasteboards,” innocent-looking pieces of printed cardstock that might just lead the unaware into a life of gambling and maybe even worse temptations. The funny thing to me, even as a kid, was that Rook cards were basically standard playing cards, just with a little cosmetic adjustment to make them palatable to stricter sorts. Where a standard deck of cards included hearts, clubs, diamonds, and spades, Rook cards were separated into suits by colors. That meant you could play all the usual games with Rook cards without even adjusting the rules. But Grandma had moved far beyond the world of Rook to play canasta regularly with her friends and euchre with us grandkids and our parents.

Over on the other side of the family divide, my paternal grandparents were equally ardent about their love of games. Lutheran by upbringing and profession (my grandfather was a minister), for Gramps and Gram, any game was—well—fair game. Most memorably, their home was the site of countless card games of pinochle. If you were fortunate, you got to be Gramps’ partner in the game, a distinct asset since he seemed uncannily capable of turning a worthless-looking hand of low denominated cards into a resource for ultimate triumph. He was also skilled at bearing in mind precisely which cards had been played in previous tricks and, therefore, what strategy to apply given which cards remained in other players’ hands. Thank goodness he never went to Las Vegas and put his skills to work for nefarious purposes!

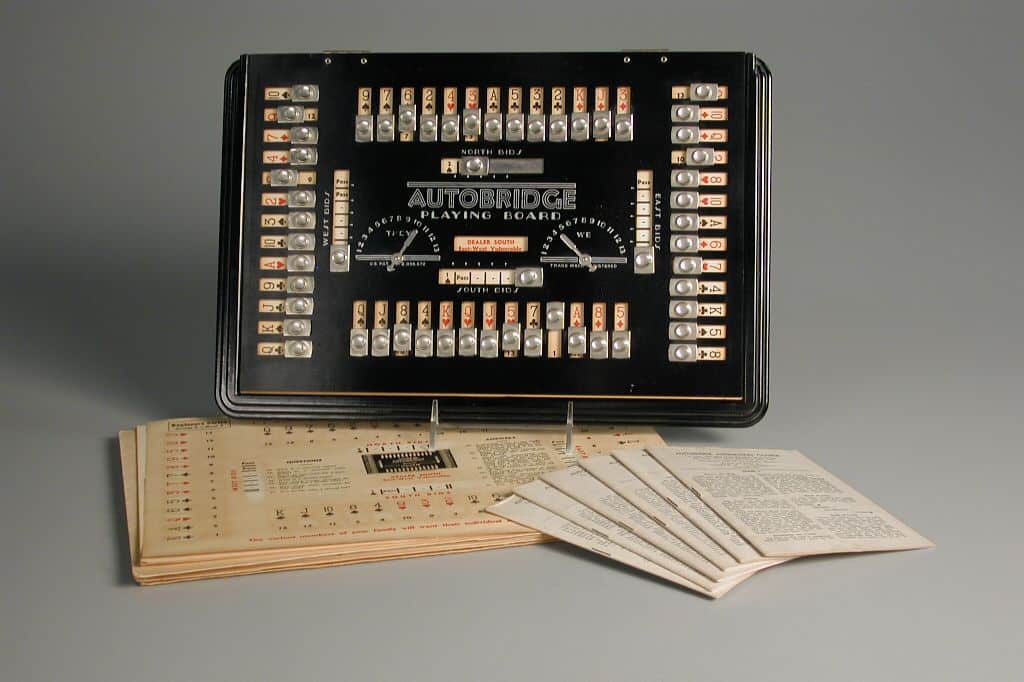

Growing up in the 1960s, I recall my parents finding themselves invited to parties to play bridge. In previous decades, that card game had emerged as a social tool in certain circles of American life. Bridge parties became fashionable, manufacturers turned out bridge accessories, and instructional materials emerged with promises of turning you into a better bridge player. My mother never considered herself a good bridge player and always felt that she was at a disadvantage in the games. Maybe that’s why our drawer of card decks also held a device called Autobridge, that allowed you to simulate playing different bridge hands with three other non-existent players. Today there’s undoubtedly an app that serves the same purpose using digital technology, but Autobridge was purely mechanical. I didn’t have a clue what I was doing at the time, but I enjoyed shoving the little knobs around on the Autobridge board to disclose the cards hidden below.

In addition to not feeling very savvy at bridge, I think what my mom objected to about bridge parties was that the other players took things “too seriously,” from her perspective. In our family, games were a source of competition but also uproarious laughter, both from the winners and the defeated. I do recall stomping off to my room in a snit on more than one occasion after being bested at a game, but the overall theme was that we enjoyed the game and we enjoyed each other. To me, that’s one of the beauties of games. Where it might feel awkward to invite someone to just come over and sit around for hours on end, a spirited game gives structure and an objective to the social event. Along with the game play, you could rely on there being plenty of conversation, stories, and genial joshing. A game created its own rationale for spending time together and appreciating the personalities and relationships around the table.

That’s why it warms my heart to see the next generation of my family continuing to use tabletop games as a reason to get together. As young adults, my nephew, my niece’s fiancé, and a group of their friends gather almost every week for extended rounds of Dungeons & Dragons. The structure is a little different from the Parcheesi and pinochle games I remember growing up, but the motivation is still the same—the unquenchable inclination to round up some congenial people, be they family or friends, and share something they all find fun. Let’s play!